by P. Andrews

The Merchant Navy, as a Service, has no real way of displaying its capabilities. There is no compulsory wearing of uniforms, no street parades led by fine military bands, no pomp or ceremony of any sort to attract the general public or media. The only attention given to the Service is when some catastrophe or other occurs which raises the hackles of the conservationists, and this always seems to be to the detriment of the Merchant Navy.

If a warship is lost, by conflict or by dereliction of duty, we never hear the last of it. If a merchant ship is lost you seldom hear of it. I wonder how many people would consult the Lloyds list of ships lost worldwide in a single year. It runs into hundreds -- ships both large and small, many of them with the loss of all hands and leaving no trace.

Merchant ships of all sizes quietly come and go. They visit ports both large and small across the world, carrying the raw materials of trade, oil and petroleum products and the manufactured goods of industry. These ships journey to and from all countries, and have been doing so for millennia. It is, however, in times of conflict that the Merchant Navy finds itself an indispensable force within the framework of military operations, and even then for safety and security reasons, a low profile is maintained.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM J03109. The S.S. Matunga carried stores, fuel and personnel of the Australian Navy and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) to New Guinea, until she was captured and sunk by the German raiderWolf in August 1917.

In wartime, nations with extensive global interests involved in such confrontations look towards their merchant ships for sea lift capabilities in the transportation of their military personnel, equipment and supplies to wherever -- and whenever -- they are required; to sustain them for the duration with the necessary arms and ammunition, fuel and food and all the paraphernalia of war; and then bring everyone safely back home again.

AWM H02227. Relatives and friends on the wharf farewelling Australian soldiers on their way overseas.

It was an accepted fact of life that the Merchant Navy would go anywhere it was sent without argument. In the Boer War, it was the Merchant Navy which took all Australia’s troops to South Africa and brought them home again safely, but then there were then no submarines, enemy aircraft or mines to worry about.

In World War 1, the first person killed was a merchant seaman, when his ship, a brigantine, was sunk by gunfire from a German submarine in the North Atlantic.

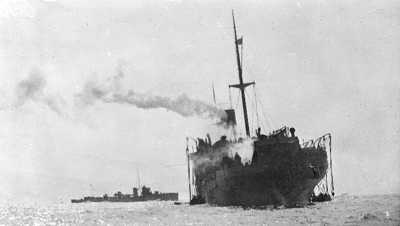

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM C01592. The WW1 transport Ballarat after being torpedoed by a German submarine off the southern English coast. In the background a British destroyer is standing by to take the troops.

In World War 2, again the first combat fatality was a merchant seaman, when a German U-boat sank the liner Athenia off the coast of Ireland -- with a heavy loss of life, both crew and passengers. The last person to die after the cessation of hostilities with Germany was also a merchant seaman, when his ship was torpedoed in the North Atlantic three days after the war ended.

Furthermore, we should not forget Atlantic Conveyor was the only British merchant ship sunk in the Falklands War but she was not the first ship sunk, for the cruiser ARA General Belgrano was sunk on 2 May and the destroyer HMS Sheffield sunk on 4 May, and others during the course of the next five weeks resulting in the death of many merchant seamen.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 302324. The merchant shipBulolo prior to being requisitioned for service as an armed merchant cruiser and later as a combined operations headquarters ship.

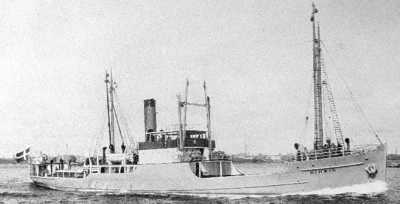

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 301760. The cargo vesselYandra before being taken up by the RAN for service as an auxiliary anti submarine vessel.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 303698. The Australian cargo vessel Nimbinwhich was sunk off Sydney on 5 December 1940 after hitting a mine laid by the German auxiliary cruiserPinguin.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 303003. Starboard quarter view of the Australian coasterBingera which was commissioned into the RAN as an auxiliary anti-submarine vessel during World War 2.

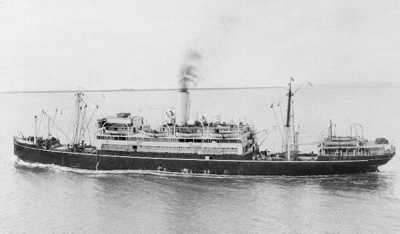

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 303741. The Australian passenger vesselOrmiston which carried Australian personnel and stores to New Caledonia in December 1941. She was damaged when torpedoed by a Japanese submarine off Coff’s Harbour on 12 May 1943.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 303583. The Australian passenger vesselManunda prior to being requisitioned and fitted out as an Australian Hospital Ship in May 1940. As such she was bombed and heavily damaged in Darwin harbour by Japanese aircraft on 19 February 1942.

It is not generally known that all hospital ships, royal fleet auxiliaries, armed merchant cruisers and most of the so-called Woolworth carriers of World War 2 were crewed by merchant seamen who sailed under the Red Ensign (Red Duster), Blue Ensign and the White Ensign. Whether they were on passenger liners, troopships, ocean going tugs, cargo ships, cross channel ferries, or fishing boats, the merchant seamen did their job without fuss and very often largely unnoticed.

Merchant ships are not built for war and merchant seamen are not trained for war, whereas naval vessels are specially designed to absorb damage from enemy attack, and their crews are highly trained in damage control and gunnery.

We in Australia and New Zealand commemorate a day which is called ANZAC Day, a day which is set aside to remember and to pay homage to our fallen comrades. This day was born out of the Gallipoli campaign, but I wonder how many people are aware of the involvement of the Merchant Navy in that campaign. The merchant ships took all of our troops to Gallipoli, and in many cases landed our troops on the beach at ANZAC Cove in the ships’ lifeboats -- manned by merchant seamen, who also came under the deadly fire from the Turkish guns.

The WW1 troopships at anchor in Mudros Harbour, Lemnos Island.

It is also interesting to note that the great majority of wounded in that campaign were taken in the ships’ lifeboats -- with merchant seamen manning the oars -- to the hospital ships which were waiting offshore. The merchant ships evacuated most of our troops from Gallipoli to Alexandria, Lemnos and Cyprus and then transported the wounded home to Australia.

Who could forget the horrors of the Atlantic convoys, in ships which in most instances were completely unable to defend themselves and were at the mercy of a ruthless enemy, day and night, for anything up to a month at a time? Between 1939 and 1945, in the so-called Battle of the Atlantic, nearly 3000 Allied and neutral merchant ships were sunk by enemy action, with a heavy loss of life. Nightmare trips to Archangel and Murmansk, suffering the rigours of an Arctic winter, while under continuous enemy attack, were endured by the crews of the merchant vessels to ensure that essential war equipment, supplies and foodstuffs got through to our Russian Allies.

Those very hard-fought convoys to the small but intrepid Mediterranean island of Malta, on which so much of the war in the Middle East depended: whether the ships came from Alexandria or by way of Gibraltar, they were under constant attack while trying to keep open the supply lines to the vital beleaguered garrison.

In August 1942, one of the greatest sea battles of World War 2, Operation Pedestal, was fought by 14 merchant ships and a large fleet of naval vessels throughout five days of continuous warfare -- from air and sea, as the fleet endeavoured to get essential supplies to Malta. Why have so many people not heard of this operation? Was it just another convoy of merchant ships? I can tell you this; we lost more men in those five days of fighting than Australia lost in the whole of the Vietnam War.

Generally, a convoy of say 45 ships usually had an escort of about four or five corvettes and maybe one old destroyer. To give you some idea of the importance of this convoy of 14 ships to Malta, we had an escort of two battleships, five aircraft carriers, seven cruisers, 22 destroyers, seven submarines and 14 other sundry naval vessels. Yet, despite this level of support, at the end of the five days, only five merchant ships had survived and three of them were badly damaged.

In the Indian Ocean, the South Atlantic and in the Pacific, the threat of surface raiders and submarines with their mine layers was ever present. Even Australian home waters were not safe; in WW2, 55 merchant ships were sunk by enemy action in the surrounding seas.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 007579. 1941, Tobruk. The effect of a thousand pound bomb on a small merchant ship lying in Tobruk harbour.

Wherever the war was being waged, merchant ships were there taking troops and essential supplies to the heart of the action. The traversing of these supply lines by these vessels and their crews, I think you will agree, was an extremely hazardous occupation. The whole maritime world was their battleground. From the moment they left port, these ships and their crews were at war, not knowing when they might be attacked, blown up or disabled in some fashion. Some statistics of the cost to the Merchant Service in World War 2 deserve some contemplation:

- 4996 British and Allied ships lost

- 62933 British and Allied merchant seamen killed in action

- 4000 wounded

- 5000 merchant seamen taken as prisoners of war.

Compare this with the 50,758 British and Commonwealth Naval personnel killed in the war. It has been estimated that the Merchant service losses amounted to one in six, compared to the combined armed forces of one in 33. It is also worthy of note that of the total casualties of merchant seamen, only 8.25 percent were wounded but 91.75 percent killed, compared with 79 percent wounded and 21 percent killed in the armed forces.

During the Falklands War, 43 merchant ships were taken up from trade (the first of these within two days of the outbreak of hostilities with Argentina) together with 24 Royal Fleet Auxiliary and Royal Maritime Auxiliary Service vessels, all manned by merchant navy personnel. Merchant ships outnumbered naval vessels in this campaign. Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse, Commander-in-Chief Fleet, said: I cannot say too often or too clearly that without the merchant ships taken up from trade and those remarkable merchant seamen, this operation could not have been undertaken, and I hope this message is clearly understood by the British Nation.

In time of relative peace, merchant seamen are often confronted by the relics of war and at times are required to enter areas of unrelated conflict. These, coupled with the inherent perils of the sea, are all taken in their stride. To those who survived, there is an obligation to ensure that those who were less fortunate are not forgotten, whether they be shipmates, friends serving in other ships, or simply bound to us by the brotherhood-of-the-sea. We are proud to be known as merchant seamen.

John Curtin, our wartime Prime Minister, said of the merchant seaman: Whenever you see a man in the street wearing the distinctive MN badge, raise your hat to him because without these gallant men the war would be lost.

Winston Churchill said on 27 January 1942: But for the Merchant Navy who bring us the food and munitions of war, Britain would be in a parlous state and indeed, without them, the Army, Navy and Air Force could not operate.

John Beasley, the wartime Minister of Supply and Shipping said on 6 March 1943:With due deference to the splendid services of the armed forces, I can say that the recent operations around New Guinea and the South Pacific would not have succeeded but for the magnificent work and courage of the Merchant Navy.

HM King George VI said: The task of the Merchant Navy is no less essential to the people’s existence than that allotted to the Navy, Army and Air Force, and indeed, none of them would be able to operate without these brave men.

And finally, in October 1945, a tribute was paid to the Merchant Navy by the British Houses of Parliament which said:

The Minister of War Transport has been informed by the Lord Chancellor and by the Speaker of the House of Commons of the terms of the Resolutions in identical terms passed by both Houses of Parliament without dissent on the 30th October 1945, of which he has been requested to communicate the following portion to Masters, Officers and men of the Merchant Navy.That the thanks of this House be accorded to the Officers and Men of the Merchant Navy for the steadfastness with which that maintained our stocks of food and materials; for their services in transporting men, munitions and fuel to all the battles over all the seas; and for the gallantry with which, though a civilian service, they met and fought the constant attacks of the enemy. That this House doth acknowledge the Merchant Navy with humble gratitude and the sacrifice of all those who, on land or sea or in the air, have given their lives that others today may live as free men, and its heartfelt sympathy with their relatives in their proud sorrow. We shall never forget them, we were forgotten!

In Memoriam Merchant Navy 1939-1945

No cross marks the place where now we lie What happened is known but to us You asked, and we gave our lives to protect Our land from the enemy curse No Flanders Field where poppies blow; No Gleaming Crosses, row on row; No Unnamed Tomb for all to see And pause -- and wonder who we might be The Sailors’ Valhalla is where we lie On the ocean bed, watching ships pass by Sailing in safety now thru’ the waves Often right over our sea-locked graves We ask you just to remember us.

Author's Note: When a merchant ship was sunk, the seaman’s pay stopped on the day of the sinking. He did not receive any more pay until he joined another ship. The seaman was given 30 days survivor’s leave, dated from the day his ship was sunk. This leave was unpaid. It only meant that he didn’t have to report back to the pool for 30 days. If he spent 10 or 15 days in a lifeboat, or on a life raft, that time in the boat was counted as survivor’s leave. There were many merchant seamen who joined the Navy because it was extremely short of experienced seamen. They joined under what were known as T124X and T124T agreements. These men were in naval uniforms on naval ships under the White Ensign, with naval officers and subject to naval discipline. They received naval rates of pay. At the end of the war, they were not allowed to claim any compensation or any benefits, because they were discharged as merchant seamen.