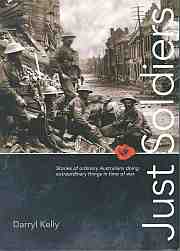

Just Solders by Darryl Kelly contains stories of ordinary Australians doing extraordinary things in time of war. In 1914, Australia had a population of fewer than 5 million, yet 300,000 from all walks of life volunteered to fight. Of these, more than 60,000 were killed and 156,000 were wounded, gassed or taken prisoner.Just Soldiers by Darryl Kelly

Through these stories, based on fact, the author has endeavoured to capture the essence of those who served Australia as members of the 1st Australian Imperial Force in the Great War of 1914-1918. As in life, not all were heroes. Illustrated with B&W images to depict the conditions under which these Australians lived and fought.

NB: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior consent of the publishers. ADCC Publications, PO Box 3246 Stafford DC 4053 - office.adcc@anzacday.org.au

To read these stories, click on the summaries below or select from the list in the left pane. The story will be loaded in this pane in Adobe PDF format. To return to the main menu, click the JUST SOLDIERS HOME link at the top of the left pane.

Sergeant Lawrence Barber. Stand alone. Lawrence Walter Barber was born in February 1894 and some might say he was destined to be a soldier. He was raised in the Sydney suburb of Granville and joined the compulsory, military cadet scheme at the age of 12.

As the line was re-established, B Company, 36th Battalion moved forward. When Captain Gadd reached the beleaguered Lewis gun position, he found Barber slumped against the gun with his face in his hands, totally exhausted. He was the sole survivor.

Captain Frank Bethune, MC. Fight to the death. Frank Pogson Bethune was a quiet, unassuming clergyman from Tasmania. He enlisted in the AIF in Hobart on the 1 July 1915 with the rank of second lieutenant. For reasons of his own, Frank chose to take up arms instead of serving as a padre.

And hold they did, for 18 days the section repulsed attack after attack. They were subjected to constant artillery barrages of high explosive, shrapnel and gas shells, but they held their ground.

Major Percy Black, DSO, DCM. On 13 September 1914, Percy Charles Herbert Black, a 34-year-old Victorian, enlisted in the AIF in Western Australia where he had been prospecting for gold. He commenced his military career at the Blackboy Hill Camp near Perth as a member of the machine-gun section of the 16th Battalion.

‘…the bravest and coolest of all the brave men I know.’

Trooper Sloan ‘Scotty’ Bolton, DCM. The Beersheba charger. Allocated initially to the 14th Infantry Battalion, Scotty Bolton was sent to the vast training camp that sprawled like a small city over most of the Broadmeadows area.

Pushing his Waler at full gallop, Trooper Bolton reached down and grasped the handle of his bayonet, extracting the 18-inch blade from its scabbard. Read more about Trooper Bolton.

WO2 Noel Eric Bolton-Wood. Age no barrier. Armed with a bogus letter of consent—supposedly written by his mother—the boy presented himself for enlistment in the AIF.1 The recruiting sergeant eyed him up and down suspiciously. ‘How old did you say you are, young fella?’ he asked.

Eric was a natural soldier and soon after being posted to the corps he was promoted to the rank of sergeant.2 At the tender age of only 16, Eric reputedly would be the youngest sergeant in the AIF.

Captain Benjamin Brodie. The raider. Benjamin Greenup Brodie was a stalwart of the unit. He had enlisted as a private and from the earliest days displayed the leadership qualities that led to his rapid promotion through the ranks.

The men listened intently as he presented the plan in intricate detail. After each was assigned his task, the CO looked at the captain and said, ‘Brodie, you’ll be leading our blokes’.

Gunner Robert Buie. Baron beware. Robert Buie was born in the little village of Brooklyn, New South Wales. He earned his livelihood fishing the waters of the Hawkesbury River, then selling his catch to markets in and around North Sydney.

As the two planes headed towards the Digger, he concentrated his sights on the second aircraft, muttering under his breath, ‘Break right. Break right’.

Lance Corporal Charles Bunney. Unmarked but not forgotten. As revellers at home ushered in the 20th century, young soldiers representing the various states of Australia were pitched in battle against the Dutch-Afrikaner settlers, thousands of miles away on the South African veldt.

Bunney, hearing the commotion, went to investigate. As Bunney entered the room, the blood-splattered Johnson attacked, striking him on the head with the axe.

Corporal Ernest Corey, MM. One of a kind. Ernest Albert Corey was born in December 1891 at Green Hills, a small town nestled in the shadow of the Snowy Mountains. A lively lad, he grew up as one of eight children born to the family.

The stretcher-bearer crawled to the wounded Digger. Assessing the situation, he grabbed the man’s thumb and rammed it into the gaping bullet hole in his leg to stem the bleeding while he ripped open a shell dressing.

Trooper Albert 'Tibby' Cotter. The last test. Albert Cotter was born in Sydney on 3 December 1884.1 He lived with his parents in the inner Sydney suburb of Glebe. From a young age, he answered to the nickname ‘Tibby’ and, like all boys, he enjoyed fishing and knocking about with his mates. But his one great passion was cricket.

The two adversaries faced each other from a little more than twenty metres. The sweat stung as it rolled down their brows and into their eyes. One contemplated his attack, the other his defence.

Lance Corporal Francis Curran, DCM. The bomber. Francis Patrick Curran was born in Tenterfield, New South Wales, in 1887. On joining the workforce, he became a carter and postman by trade. Young Frank was also a very keen sportsman, excelling at football and boxing. In September 1914, Australia, now at war by virtue of being a member of the British Commonwealth, called for volunteers to join a military force to go to Europe to fight the German oppressors.

With the skill and athleticism of an A-grade cricketer, the khaki-clad figure repeatedly fielded the hissing bombs in mid air as they flew towards him. With no time to hesitate, yet with deadly accuracy, he hurled them back to their senders.

Bombardier Cecil Edwards, MM. The artillery signaller. Cecil Francis Edwards was barely nineteen when Great Britain declared war on Germany. Cec was among the first to join the long queues of young Australian men eager to volunteer to serve their King and country.

The concussion of exploding shells rocked their senses. The screech of artillery fired from the field guns of both sides was deafening . . . but communications had to be maintained.

2Lt Henry ‘Ernie’ Eibel. The iceberg. On 21 September 1914, barely six weeks after the outbreak of the First World War, Henry ‘Ernie’ Eibel enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Like so many of the early volunteers, Ernie was a country lad.

Long, black belts of thick barbed wire formed a formidable barrier. Beyond the wire were reinforced concrete pillboxes, the deadly barrels of machine-guns jutting from the openings. The air was thick with bullets and the red-hot splinters of artillery rounds.

Private Edward Elart. A man with a secret. As eager young volunteers skirted around him, a young man paused and stared intently at the building that housed Naval Headquarters. He was poised to go in, but, on the threshold, he changed his mind. Instead, he turned on his heel and headed towards the military barracks down the road, where some time later he stood before the officer, raised his right hand and pledged, ‘I, Edward Elart, do hereby swear…‘

On the night of 6 June, he was ordered to go out again. ‘I’ll need a couple of blokes to go with me’, Freame said. A newly arrived lad by the name of Morris said he’d go and the other volunteer was Edward Elart.

Sergeant ‘Harry’ Freame, DCM. The ANZAC ‘Bushido’. Harry Freame was born in 1880 in the Japanese city of Osaka. His parents were William Freame, an Australian working in Japan as an English teacher, and Shizu Kitagawa, whose Japanese ancestry dated back to the Shoguns of the 16th century.

Then, knowing that the information he had gathered was required by his commanding officer, Freame sprinted down the valley, drawing a furious hail of Turkish rifle and machine-gun fire as he went.

Chaplain Alfred Goller. The insubordinate padre. Alfred Ernest Goller was born in Bannockburn, Victoria in July 1883. His parents were simple people with strong religious convictions, who had raised their son with the same set of values. Until the outbreak of war in 1914, he served the church in the Victorian country areas of Birchip and Mia Mia.

The commanding officer (CO) said, ‘You can fall out too, Padre'. ' No Sir’, was the reply. ‘If ever the men needed a chaplain, they need one now’.

2Lt Robert Graham, DCM. The soldier of fortune. Robert Louis Graham was born in Canada on 16 April 1876. The son of a superior criminal court judge, he spent much of his vacation time as a youngster among the friendly Indian tribes of central Canada.

When Bob Graham presented himself for enlistment in the AIF, the crusty old sergeant manning the desk asked, ‘Have you had any military experience, mate?’ ‘Yeah, a bit’, Graham replied.

Private John ‘Barney’ Hines. The souvenir king. Born in Liverpool, England, Hines gave his age as 36 and his occupation as comprising a variety of trades—seaman, engineer, fireman, deep-sea diver and shearer. This was not Barney’s first experience of military life.

Later that day, Hines ventured out alone and destroyed another German machine-gun post. He was wounded during this latter action and spent the next six weeks recuperating in hospital.

Private Edwin Hoare. Sorry mother. Edwin Cooper Hoare was British, born and bred. He worked hard as a fruit farmer to help support his parents. At the end of a hard day’s work, the young lad often wandered through the fields that surrounded his home in Hastings. He would try to imagine the famous battle that had been fought more than eight hundred years ago on the very ground where he now sat.

‘Why don’t you save your fight for the Germans, you pommy git?’ snarled one of the offenders. ‘What the hell would you know about fighting Germans?’ the young Englishman retorted.

Lt Andrew Kirkwall-Smith, DSC, MM. Distinguished service in two wars. Andrew Kirkwall-Smith was born and raised in the tiny Scottish town of Kirkwall on the Orkney Islands. In the early 1900s, his family decided to escape the harshness of the Orkneys and try their luck in Australia.

He hid amongst the mangroves, his face buried in the mud. They were so close he could see the stitching on their boots. He dared not breathe. Discovery would undoubtedly result in his death.

Sergeant Donald MacKechnie. The fraud. Prior to joining the AIF, 36-year-old Donald MacKechnie had served for 12 years in the British Army. As a young private in the Gordon Highlanders, he was a member of the Tirah Expedition of 1897, sent to quell a local uprising in north-western Afghanistan.

On the 18 April 1915, the army had had enough of MacKechnie’s antics and he was brought before a general court martial on a charge of drunkenness.

Lt Col Charles Macnaghten, CMG. The Duntroon deserter. Charles Melville Macnaghten was born in Rhutenpore in the Nuddhoea district of Bengal, India, on 18 November 1879. He was the son of Sir Melville Macnaghten who, in 1889—as Assistant Chief Constable, second in command of the Criminal Investigation Department at Scotland Yard—was a leading investigator in the ‘Jack the Ripper’ murder case.

Macnaghten was leading some men forward again when he was shot through the chest. He tried to stay on his feet, but was shot again, this time through the throat. He staggered back to the dressing station, cursing his bad luck and wishing he could get back to the line with his men.

Private William ‘Harry’ Malthouse. Shattered hopes. ‘Harry’ Malthouse presented himself for enlistment in the AIF on 13 July 1917, lowering his age by seven years to 46.

In late November, Phelps appealed to the doctor, once again, to allow Malthouse to be repatriated. The doctor considered carefully before he placed the old man’s name on the list of those to be sent home.

LCpl John Mann, DCM, MM. The Lewis gunner. John Henry ‘Jack’ Mann was born in England. Yearning for adventure, he set sail from his home to see the world. After a stint on the South African goldfields, Jack worked as a crew member on a windjammer that travelled the route between the Cape of Good Hope and the west coast of Australia, where the promise of riches attracted him to the local goldfields.

Jack Mann had survived his first terrifying battle. He had put drum after drum of ammunition through his Lewis gun and he had been responsible for his fair share of enemy casualties.

Privates Ina and Clement Moore. The twins. As he passed the wriggling bundle to the midwife to clean and clothe, the doctor turned to the mother and said, ‘You have to keep pushing Mrs Moore, there’s another one’.

‘I’ve got something else of his too, mate. Here’s his notebook’, the other said. On comparing the items, they realized the initials were different. ‘Wonder if they were related?’ one asked.

Private Joseph Newman, MM. One that got away. Joseph Lewin Newman was posted to ‘C’ Company of the 2nd Division’s, 17th Battalion. He commenced military life at the main training camp at Liverpool, NSW—a vast ‘city’ of canvas stretching along the flat eastern bank of the Georges River.

Late one night, under the noses of guards—who still believed there was no risk of escape—Newman and his two comrades climbed out of a window and simply vanished into the darkness.

Private Arthur Oldring. No place to hide. On 27 December 1916, a 44-year-old man with ferret-like features walked into the Adelaide recruiting centre to enlist in the AIF. Giving his name as Arthur Geoffrey Oldring, the man was allocated as a reinforcement to the 8th Machine Gun Company and was sent to the Victorian town of Seymour for basic training.

As the brown, swirling waters of the flooded Goulburn River rushed by, a terrified woman watched transfixed as the blunt end of a tomahawk was swung towards her head.

Sister Alice Ross-King, ARRC, MM. Front-line angel. Alys Ross was born in the Victorian town of Ballarat, in August 1891.2 She was of hardy Scottish stock and while she was still a toddler, her father had moved the family to Perth in search of a better life.

She heard the whistle of falling bombs just before one of the missiles exploded directly in front of her, knocking her to the ground.

Private Alexander Sast. Unbroken silence. Russian-born Alexander Sast was no stranger to military service. After completing his training as a fitter with the Government Railways in Odessa, he enlisted in the Russian Navy and served for five years in the Baltic Fleet. Yearning for a better life, he left the Navy and made his way to Australia.

The strong smell of ammonia permeated the nostrils of the unconscious form suspended from the ring attached to the ceiling. The Digger stirred in response, roused by the smell and the excruciating pain in both arms and shoulder joints.

Private Noble Stephenson. Dead or alive? Noble Stephenson had been a member of the local militia unit for the past six months and he knew exactly what those words meant. He felt sure that he would be called upon to do his bit.

She looked deep into the soldier’s eyes, then turned to the officer, shook her head and said, ‘No, it isn’t’.

Private Stanley Treloar, MM. The pocket dynamo. Stan Treloar, a nuggetty little fellow from Creswick, Victoria, was the son of a minister, but he possessed a larrikin streak that did not conform with one raised in such a religious family.

When the danger had passed, Stan got up, shook off the dirt and turned towards where he’d last seen his mate ‘C’mon cobber, let’s keep going.’ But his friend could not answer—he’d been blown to bits.

Gunner William Vandertak. A fight for a belief. William Vandertak was 22 years old when he enlisted in the AIF, following the outbreak of the Great War. A labourer from Wagga Wagga, Vandertak was assigned to the 13th Battalion of the 4th Brigade.

When he entered, he could not believe his eyes. An Australian officer was toasting the Kaiser’s health. The usually quiet Vandertak was overcome by a fit of rage and disgust. He stormed towards his superior and angrily tore off the offending officer's insignia of rank.

Private Richard Warne, MM. Within sight of home. Richard Warne was born to simple country folk in Maryborough, Queensland, in 1898. A boy of the land, he worked hard on the family farm at Owanyilla in support of his family’s endeavour to eke out a living.

The sequence of events that followed can only be described as a horrible twist of fate. The train was going too fast.

Lance Corporal Vernon Warner. Lucky to be alive. As the ranks of the 4th Battalion came into view, Enid Warner struggled to see through the cheering crowd standing shoulder to shoulder on both sides of the street. She was desperate to catch a last glimpse of her husband, Vernon.

The soldier contemplated the empty sleeve of his pyjama coat then turned his attention to the damaged bible he held in his hand. He stared long and hard at the bullet that lay embedded in the pages of the book as he came to grips with how close he had been to death.

Sergeant William Wass, MM. Only a dog tag. William Wass was born in Derby, England. He chose the life of a professional soldier and at an early age enlisted in the British Army, assigned to the local regiment, the Sherwood Foresters.

The machine-gun fire was murderous; it seemed to be coming from all directions at the same time. The Diggers unsuccessfully tried to edge their way forward as time and time again they stopped to burrow their faces into the ground in an attempt to avoid the barrage of bullets.

Corporal William Webb. The survivor. William Purnell Webb was born in Cheddar, England in October 1896. He came to Australia in search of a better life. On 6 February 1915, young Bill enlisted in the AIF. A competent horseman, he was allocated as a reinforcement to Queensland’s 11th Light Horse Regiment.

‘Are you American?’ came the question from the direction of the ship. ‘No,’ replied the POWs. ‘Are you British?’ ‘No, we’re Australian,’ shouted the prisoners.

Private Charles Williamson, MM. Ask no questions. The man who appeared, wraithlike in the dust of ANZAC, was already the veteran of a number of military campaigns. English born and bred, Charles Williamson initially joined the militia, serving as a soldier of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers. In April 1898, he decided to move to full-time soldiering, joining the crack Coldstream Guards.

Williamson heard that a particular French officer was among the missing. Obsessed with finding this man, he sortied out in search of the officer’s body, but instead, found scores of wounded soldiers.

WO1 Frank Wittman. Determined to serve. Frank Wittman was born near the central Victorian town of Warragul. On completion of his studies he became a pharmacist and a podiatrist and operated successful pharmacies in Melbourne.

The minimum height for eligibility to enlist in the Australian Imperial Force was 5 foot 2 inches (1.55 metres) but Wittman stood a mere 3 foot 8 inches tall (1.12 metres).