Initial Reactions

When war broke out in September 1939 the Australian Government was much better prepared for it than in 1914. As in 1914 most Australians seemed to support the decision to be involved in the war. All major political parties, churches and newspapers supported involvement. The only groups not to support the decision were pacifists such as Jehovah's Witnesses, and hard core socialists who opposed involvement because the Soviet Union opposed it.

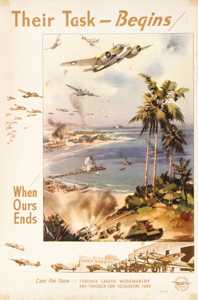

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ARTV09061.

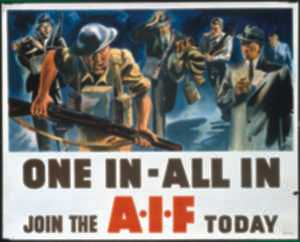

Nor was there the same rush to enlist. The government deliberately moved more slowly and in a more organised way -- they had learned from 1914 when many men in essential occupations had been allowed to enlist, to the detriment of the home front effort.

From 'Phoney War' to 'All In'!

For those in Australia, the first few months were a period of 'phoney war', when there was little actual combat for our troops and life at home for Australians at this stage was fairly normal.

In June 1940, however, the German war machine struck, and the countries of Europe rapidly fell to the German Blitzkrieg of 'lightning war'. By September only Britain stood undefeated, and even then it had been badly mauled at Dunkirk, and was suffering the impact of the bombing of its industrial cities. The war was increasingly desperate and serious.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ARTV06766.

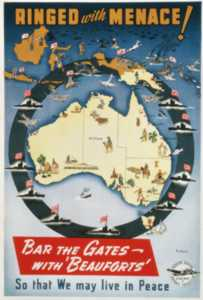

With the entry of Japan into the war there was a real fear and the threat of an invasion to Australia. During 1942, civilians were evacuated south in Western Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory and Australians were put under greater government controls than at any time since the convict era. There have never been such controls since that time.

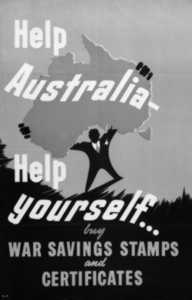

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ARTV062721.

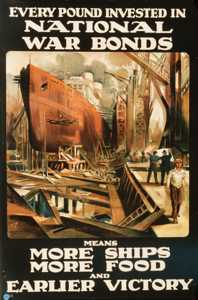

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ART04273.

Government Controls

As in World War 1, the Commonwealth Government imposed a large number of new controls over people's lives. They did this through the authority of the National Security Act of 1939. This Act did two major things: it effectively overrode the Constitution for the duration of the war - giving the Commonwealth power to make laws in areas where it did not have that power under the Constitution; and it effectively overrode the power of parliament by giving the government power to make regulations, that is, laws that required only the signatures of some ministers and the Governor-General.

The government used its powers to make a huge number of laws and regulations affecting all areas of people's lives. Among these were:

- the reduction of the Christmas - New Year holiday period to three days;

- the restriction of weekday sporting events;

- blackouts and brownouts in cities and coastal areas;

- daylight saving;

- increased call-ups of the Militia;

- the issue of personal identity cards;

- increased enlistment of women into the auxiliary forces;

- regulations allowing strikers to be drafted into the Army or into the Army Labour Corps;

- the fixing of profit margins in industry;

- restrictions on the costs allowed for building or renovations;

- the setting of some women's pay rates at near-male levels;

- internment of members of the Australia First organisation;

- controls on the cost of dresses;

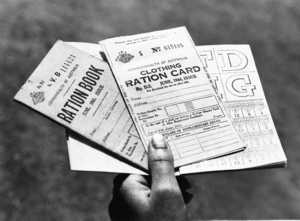

- the rationing of clothing, footwear, tea, butter and sugar;

- the banning of the Communist Party, and the Australia First Movement for opposition to the war;

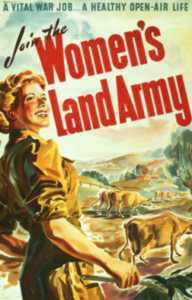

- the formation of a Women's Land Army;

- the pegging of prices; and

- the prosecution of about one thousand conscientious objectors, and the imprisoning of some of them.

Equality of Sacrifice

The Australian people went through six years of war with considerable unity. Of course there were many divisions and tensions, but overwhelmingly the people seemed to be quite united, particularly in comparison to the World War 1 experience.

Part of the explanation for this could be the reality of the threat to Australia for much of the war. Once the phoney war period was over, the Germans were clearly poised to defeat all of Europe, including Britain. British cities were suffering nightly aerial bombing, and the German submarines were able severely to restrict equipment and supplies reaching Britain. Then, with the entry of Japan into the war in December 1941, the Australian mainland itself seemed vulnerable to an invasion.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ARTV06426.

In the Battle of the Coral Sea of 4 to 8 May 1942, a Japanese fleet was intercepted by a force of United States, Australian and New Zealand vessels. The battle was a defeat in that the Allies suffered greater losses. But the battle helped to prevent the landing of Japanese troops on the south coast of New Guinea, where they could have put Australian troops under a great threat, and it weakened the Japanese Navy for the Battle of Midway one month later, when they were defeated in the decisive naval battle of the Pacific.

This sense of fear and uncertainty of victory had diminished by 1943, but the war still remained to be won right up until 1945. This perception of the seriousness of the war meant that most people shared the same sense of priorities about the war, which in turn created a united approach.

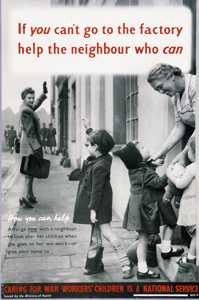

A second possible factor was that all people were able to contribute to the war effort in a meaningful and valued way.

Contributions were coming not only from those in the employment of direct war related industries as even the most normal and routine of events - a housewife shopping and cooking for her family - were seen to have a war-related significance. Rationing and shortages meant that there was emphasis on the 'kitchen front'.

While the urgency of the war and the severity of shortages started to be reduced after 1943, there was still an 'All in' emphasis till near the end of the war. And even though black-marketeering developed during the war, most of it was on a very small and tolerated scale, and was not divisive. The large-scale organised rackets which developed in some places were, however, severely opposed.

Women

Did the war change the role and place of women in Australian society?

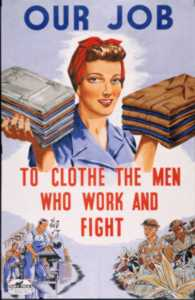

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ARTV00332.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 029692. Members of the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force cleaning and overhauling a plane of the RAAF.

Propaganda at the time stressed that for the first time women were being asked to do 'a man's job', either in the Services or in industry. Certainly more women entered the workforce than had been there before, and many took on jobs that had previously been available to men only. These women gained all, or nearly all, the male rate for these 'men's jobs'. However, most of the new women workers went into traditionally female areas, where the wage was typically 54 per cent of the male rate - though by the end of the war was closer to 70 per cent.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 014929. Australian Land Army girls doing their bit to assist in the war effort. They are harvesting large crops of vegetables which are being canned for the troops.

Women who entered the Services were also paid at a far lower rate than their male counterparts doing exactly the same job - these jobs disappeared at the end of the war. The Service experience, however, did have a profoundly liberating effect on many women, who then sought jobs after the war that would maintain this independence and liberation. Many others, however, were happy to return to normal domestic life after the war.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ARTV01062.

Modern histories of the home front war all pay homage to the active role played by many women during the war. However, the fact also remains that the single most common women's experience of war was to remain at home and not be employed. For many, this role took on new aspects, as women became financial heads of their households with the male breadwinner away. This meant that many had problems giving up this responsibility after the war - but again, many were anxious and pleased to return to pre-war 'normality'.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ARTV01064.

While the activities of groups such as the Women's Land Army are praised for being helpful to the war effort, we must not forget or undervalue the contribution of many thousands of farming women for whom sharing farm work was a normal and vital part of the pre-war economy. These women do not appear in statistics, but they provided far more and over a longer period of time than was provided by the new organisations.

Americans

One of the most severe tests of the Australian public in war was the presence of large numbers of United States troops in transit through Australia to various war fronts. These troops had three major impacts on Australian life.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 012176. American servicemen were welcomed into Australian homes - providing a home life they thought they had left behind.

One was to force the opening up of major cities to new cultural ideas - in particular, to bring entertainment to what were very closed-down cities at weekends. The Australian tradition was for cities virtually to shut down on Saturdays and Sundays. The presence of thousands of troops in many capital cities led city leaders to change that policy, and to open hotels, theatres, clubs and restaurants for longer and more varied hours. This in turn had a substantial impact on the local economy, and introduced new tastes and fashions.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 011546. US sailors and soldiers on their arrival in Australia quickly made friends wherever they went, and were received with the hospitality for which Australians, like Americans, are noted.

A second impact was the creation of considerable rivalry between Australian and American troops, and jealousy on the Australians' part. The American troops were better paid and - with their access to consumer items in their PX (a supermarket set up exclusively for American defence personnel) and services like taxis - were able to live more lavishly and comfortably than the local Australians. This in turn led to some women preferring the Americans socially.

This climaxed in a number of clashes between Australian and American troops in Melbourne, Perth and especially the infamous 'Battle of Brisbane' where hundreds of troops fought viciously in the city streets.

It is important, however, not to overemphasise these events. Many, perhaps even most Australian women, probably never met, let alone went out with, an American soldier. And the 'battles' between the troops involved only the tiniest minority of soldiers on each side.

A third impact was on Australia's indigenous people. Many black Americans were among the troops who passed through Australia. While blacks were discriminated against in the United States, they had far more civil rights than Australia's indigenous people. Many indigenous Australians met with these Americans, and were deeply influenced by the possibility for greater civic and economic equality that they seemed to represent.

Economy

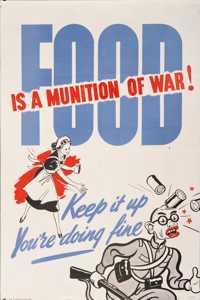

The war was a huge boon to the Australian economy. As many Australian primary products were purchased as could be produced, and secondary industries manufactured many new items for the Services. Rationing and restrictions meant that there were few consumer goods available, so personal savings rose. Man powering and essential industries also meant that there was near-full employment.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 042770. Ration books for food and clothing.

Conscription

In 1943 the issue of conscription arose.

As in 1916 and 1917, the government had the power to conscript men for home service, but not for overseas combat. 'Home', however, included New Guinea, where Australia had a protectorate, and therefore conscripted troops could be and were sent to the war front where they were needed most.

But as the Allies began to defeat the Japanese, the war front spread north, and there was a demand that Australian troops be able to go to the new areas which were outside the definition of home. American conscripts were fighting in these areas so it seemed unfair that Australian conscripts should not also be compelled to fight there. As in 1916 and 1917, all the government had to do was to change the Defence Act and it could achieve this - unlike the situation in 1916, Prime Minister Curtin knew he had the majority in both Houses to make this change.

Cabinet approved the Defence (Citizen Military Forces) Act 1943, which provided for the use of Australian conscripts in the South West Pacific Area during the period of war. The Act also provided that this approval would lapse within six months of Australia’s ceasing to be involved in hostilities.

He did not, however, push the measure through. Rather, he let the Australian Labor Party debate the issue, and come to their own decision which was to support the extension of areas where Australian conscripts could be sent to fight. This debate within the party allowed the opponents to be heard, but also showed how small a minority they were. This avoided a potentially ugly and divisive public brawl on the issue.

The Act was changed, the area where conscripts could be sent was extended - though still strictly limited - and it was all done with little opposition in the community.

Indigenous Australians

The war had a great effect on the place of indigenous people in Australia. Large numbers of men and women joined the services or worked in war industries - and received greater training, pay and social contacts than many had received before. As Oodgeroo Noonucal, the poet and political activist and signaller in the AWAS said, 'There was a job to be done… all of a sudden the colour line disappeared.' For many non indigenous Australians this was their first real contact with Aboriginal Australians.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 139015. An Australian Aboriginal woman studying her new ration book.

Many indigenous people also had contact with black American troops in Australia, and saw them with skills, money and a greater sense of civil rights.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM P2104.004. These soldiers are part of a special platoon consisting of aboriginal soldiers, all volunteers, at Number 9 camp at Wangaratta. Major Joseph Albert (Bert) Wright, a World War 1 Light Horse veteran, was in charge of this platoon, which was the only Aboriginal squad in the AMF (Australian Military Forces).

National Identity

There was no event in World War 2 that had quite the same significance for Australian identity as Gallipoli. The gallant fight by the untrained men of the 39th (Militia) Battalion in holding up the advance of the Japanese along the Kokoda Track towards Port Moresby was a major event. It was even claimed by Prime Minister Keating in 1992 to be 'the place where I believe the depth and soul of the Australian nation was confirmed'. Public celebration of the event does not seem to confirm that view. There has also been a great emphasis on integrating the Prisoners of War of the Japanese into the ANZAC idea, stressing their mateship, endurance and resourcefulness. But neither of these has generated the power of Gallipoli nor the Western Front experience on Australian identity.

National Independence

There were five points during the war at which we can see Australia either asserting its identity, or remaining tied subserviently to another nation.

In 1939, Britain declared war against Germany - Prime Minister Menzies announced that we were therefore also automatically at war. As part of a pre war agreement commitment, Prime Minister Menzies turned the Navy over to effective control by Britain as part of the Royal Navy. Menzies also committed Australia's Air Force to British command for use in the war over Europe, and in effect the RAAF's main role became training Australian crews to be used in the RAF. This later severely restricted the RAAF's capacity to play an effective role in the Pacific War.

In December 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbour and then Singapore, Australia declared war on Japan. We did not wait for a British declaration, nor did we consider ourselves a part of the British declaration.

In late 1941 and early 1942, as Japan stormed into the war and invaded New Guinea, most Australian troops were in action in the Middle East. Australian Prime Minister Curtin wanted the troops to return to Australia, to be sent to New Guinea. British Prime Minister Churchill wanted to send the troops to Burma to take on the Japanese there, assuring Curtin that this was the better strategy, and that New Guinea could be dealt with later. Curtin's decision won the day.

One effect of that was that the Commonwealth Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act. The Statute of Westminster was a British Act which said in effect that when a Dominion adopted it, the British Government could no longer make any decisions for that Dominion. It had been available to Australia since 1931, but was only adopted in 1943.

In December 1941, Curtin wrote an article for the Melbourne Herald, in which he said: 'Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.' The United States needed Australia as a supply and staging post for its Pacific War efforts; Australia needed the USA to be active and aggressive in the Pacific.

United States troops started pouring into Australia from Christmas Eve 1941. The American General Douglas MacArthur was the supreme commander of all Allied forces in the Pacific. He insisted that he deal only with Curtin. Curtin looked to him for military advice and expertise, and in effect withdrew Australian influence from the running of the war. Some historians see this as a 'surrendering of sovereignty'. Towards the end of the war Australia's interests were perhaps not well served as MacArthur deliberately cut the Australians out of the war effort - committing them to a series of 'mopping up' campaigns against the Japanese that were of doubtful strategic value, but were costly in Australian lives.

The Enemy Within

About 43 per cent of the 52,000 people defined as 'aliens' during the war were classed as 'enemy' - mainly Germans, Italians and Japanese.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 030242/13. Family groups of German Internees at No. 3 Camp, Tatura Internment Group.

The Italians were the largest non-British group in Australia. When Italy entered the war in June 1940, a number of these were interned, and many suffered assaults and harassment. The strongest reaction was in Queensland, which had the largest population of Italians, and where people were also more vulnerable to an invasion.

However, as labour became scarce, and as Italian military involvement collapsed during the war, many internees were freed to work on civilian labour schemes. Many Italian prisoners of war also were released to work on farms.

Everyday Life

The realities of life changed greatly for many people. There were shortages, rationing, constant fund-raising appeals.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ARTV05272.

With one million men and women in the Services, most families were disrupted. The war probably changed many Australians' sense of the geography of the place, as many were stationed overseas or in parts of Australia they may never have seen before this time.

One of the great demographic changes was the increase in marriage rates, and the lowering of the average age on marriage of both men and women.

Legacies and Impacts

One of the main effects of the war was to start the 'migration revolution' of postwar Australia. The Australian Government had fears of an invasion, and believed that we had to 'populate or perish'. Migrants from traditional sources were not available in large enough numbers so Australia started accepting refugees and displaced persons from the northern and eastern European countries.

This was the beginning of the end for 'White Australia' and the start of modern multiculturalism.