The Australian Flying Corps

In 1914 Australia’s only military aviation base, the Central Flying School, newly established at Point Cook, was equipped with two flying instructors and five flimsy training aircraft. From this modest beginning Australia became the only British dominion to set up a flying corps of its own for service during the First World War.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ART03029. Will Longstaff, War planes of the Australian Flying Corps, 1918-1919, Painting: oil on canvas, 236 x 141 cm.

Known as the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) and organised as a corps of the Australian Imperial Force, its four line squadrons usually served separately under the orders of Britain’s Royal Flying Corps. The AFC’s first complete flying unit, No.1 Squadron, left Australia for the Middle East in March 1916. By late 1917 three more squadrons, Nos.2, 3, and 4 had been formed to fight in France. A further four training squadrons based in England formed an Australian Training Wing to provide pilots for the Western Front.

Before No.1 squadron made its journey to the Middle East, Australian airmen had been in action in Mesopotamia. A Turkish threat to the Anglo-Persian oil pipeline and the strategically important area at the head of the Persian Gulf (the Shatt-el-Arab) convinced British strategists of the need to open a second front against the Turks. The Australian Government was asked to provide aircraft, airmen and transport to support the Anglo-Indian forces assigned to the campaign. It responded by dispatching four officers, 41 men, and transport—called the Mesopotamian Half Flight—in April 1915. Arriving too late to help secure the Shatt-el-Arab and the oil pipeline, the Half Flight joined the British advance on Baghdad, an operation intended to exert additional pressure on the Turks in the east.

The attempt to reach Baghdad failed, and some 13000 British and Indian troops found themselves besieged by superior Turkish forces in the city of Kut, about 80 miles south of their objective. Attempts to relieve the siege failed, and in April 1916 the garrison at Kut, including members of the Half Flight, surrendered. Taken prisoner by the Turks, few survived captivity. The defeat on the Tigris marked the end of Australia’s first experience of military aviation. The Mesopotamian Half Flight and No.1 Squadron were both formed early in the war, when military aviation was in its experimental stages, and both contained some of Australia’s aviation pioneers.

Throughout 1916 and much of 1917 No.1 Squadron flew inferior aircraft such as the BE2c against German opponents who, supporting the Turkish armies in the Middle East, were equipped with more advanced Fokkers and Aviatiks. However, by the end of 1917, newly equipped with Bristol Fighters, the Allied airmen began to gain the ascendancy.

Arriving in England between December 1916 and March 1917 and doing eight months training before being sent to the Front, 2, 3 and 4 Squadrons began their active service at a time when the use of aircraft in war was far more developed.

It was different for members of the AFC who served in the Western Front squadrons. The days when enemy airmen waved to each other on reconnaissance flights were long gone. Aircraft now carried machine guns as standard equipment, and interrupter gears, developed in 1915, enabled pilots in single-seat fighters to fire straight ahead through their propellers.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM P00449.004. 5 October 1914. Lieutenant W.H. Treloar, Australian Flying Corps, in the cockpit of his aircraft. Treloar was one of the officers of the Mesopotamian Half Flight..

By 1918 aircraft were being used in a variety of roles: some as fighters, others for reconnaissance or artillery spotting and others for bombing operations inside enemy territory.

The AFC’s best aircraft in the final year of the war were among the most technically advanced of the day. Bristol’s BF2b, a two-seat fighter-bomber known as the Bristol Fighter, could climb to 10000 feet in 11 minutes and fly at 113 miles an hour when it got there. The famous Sopwith Camel could reach 12000 feet in 12 minutes, fully loaded with weapons and ammunition, and fly as quickly as the Bristol Fighter. Pilots and observers sat exposed to the elements in noisy open cockpits.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM P01976.001. England. April 1915. Starboard side view of a Maurice Farman Longhorn 2960 two-seater biplane used as an elementary trainer aircraft for the Australian Flying Corps.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM E02655. Group portrait of Officers of C Flight, No. 4 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps (AFC) in full flying gear, about to take the air—standing in front of a Sopwith Camel aircraft.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM E02332. 15 May 1918. At this time this AFC Squadron was very actively supporting the troops on the Western Front. Note the tail of the aircraft is supported so the aircraft can be in a level position for testing machine guns on the range prior to an offensive patrol.

Given the nature of warfare on the Western Front, it is not difficult to imagine why men would seek to transfer into the AFC. Many had experienced the misery and squalor of the trenches. Those who knew they would face danger as long as they were in the AIF preferred to face it in a corps which offered the promise of independence and glamour, as well as a degree of comfort unknown to the men in the trenches. Those who served in the Middle East, although spared the worst miseries of the Western Front, shared a similar desire to escape their own discomforts: the sand, the dust and the flies. Men who had already served in the ground forces reasoned that if they survived the day’s flying they would at least have the chance to sleep in a comfortable bed.

Not everyone, however, survived the day’s flying. Many pilots were killed in accidents long before they could join a line squadron. Over a third of the AFC’s wartime fatalities occurred in Britain. Some trainees died even after the war had ended: as one pilot wrote in March 1919:

A great pal of mine was on his very last flight — his last test before qualifying … a mist arose, he flew into the ground and was killed. He had enlisted in 1914, gone through much front-line service, only to be killed on his absolute final exploit, four months after the armistice.

Pilots who survived training were posted to operational squadrons where the thought of meeting the enemy in the sky was enough to give even the bravest men pause for thought. Harry Cobby, who went on to become the AFC’s leading ace, admitted his own fear at the thought of being posted to the front:

The nervousness that assailed me during the months of training in England, when I gave thought to the fact that as soon as I was qualified to fly an aeroplane, or perhaps sooner, I would be sent off to the war to do battle with the enemy in the sky and on the ground. I quite freely admit that if anything could have been done by me to delay that hour, I would have left nothing undone to bring it about.

Cobby overcame his early fears to become a highly successful pilot. Others were less skilled or less fortunate. Owen Lewis, an observer in No.3 Squadron, was an experienced airman. An entry in his diary on a day when bad weather prevented flying reveals his feelings about operations: ‘This morning I was pleased when the weather was fairly dud -- I am afraid I am always pleased when that is so.’ His fears were justified. On 12 April 1918, the day after he had teamed up with a new pilot, both men were killed in action.

Two main types of aircraft were used by the AFC: two-seater reconnaissance planes, in which the observer, armed with machine guns, sat behind the pilot; and single-seater fighters. The latter dominated the popular imagination: they were the aces, flying the fastest aircraft and fighting duels with men like themselves above the trenches. In reality, aerial combat was a difficult skill to master, requiring split-second timing and complete mastery of one’s aircraft and weapons. A man in No.1 Squadron described a dog-fight as:

Every man for himself. We go hell-for-leather at those snub-nosed, black crossed busses of the Hun, and they at us ... Hectic work. Half-rolling, diving, zooming, stalling, ‘split-slipping’, by inches you miss collision with friend or foe. Cool precise marksmanship is out of the question.

He was in fact the observer in a two-seater and thus did not have the opportunity to use a forward firing machine-gun. Those like Cobby who flew in fighters also found that in a dogfight, which by the end of the war, could involve up to 100 aircraft, hitting the enemy was very difficult:

The air was too crowded, there was little opportunity to settle down and have a steady shot at anything. You would no sooner pick out someone to have a crack at, than there would be the old familiar ‘pop-pop-pop-pop’ behind you, or you would just glimpse an enemy pilot getting into position to fire on yourself — so hard boot and stick one way to save your skin.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM B02078. Pilots of the Australian Flying Corps in a Bristol Fighter machine. The twin Lewis guns with which these aircraft were equipped are shown in the rear.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM H12729/07. An Avro DH 5 fighter aircraft, found by the Australian Flying Corps to be a very good machine.

Most of Cobby’s kills appear to have been scored against unsuspecting victims over whom he had the advantage of surprise and speed.

When two skilled opponents met in the air, the fight was often lengthy: both men knew that only one would survive. The German airman, Ernst Udet, described one such combat: ‘I tried every trick I knew, turns, loops, rolls and sideslips — but he followed each movement with lightning speed and gradually I began to realise that he was more than a match for me … the man was a superior duellist.’ When his guns jammed, Udet thought he was doomed; but he was lucky—his antagonist turned his aircraft upside down, waved farewell and dived towards the Allied line.

As Udet discovered, the air war could sometimes be chivalrous. As the Australian historian, F.M. Cutlack, wrote ‘the star airmen of the opposing armies regarded each other with a curious mixture of personal esteem and deadly hostility.’ Many toasts were drunk to Richthofen by men who would have gladly killed him given the chance. When he was killed, Australian airmen placed wreaths on his grave. In the Middle East Oberleutnant Gerhardt Felmy, the leading German pilot facing No.1 Squadron, earned the admiration of his adversaries. It was not uncommon for him to drop messages from and photographs of recently captured Australian airmen on their home field. The Australians did the same for the Germans and drank toasts to Felmy in their mess. On the Western Front captured enemy pilots were treated with respect by their Allied counterparts and vice-versa. In practice there was not much room for chivalry. In 1918 Australian pilots on the Western Front flew regular operations against enemy forces on the ground. ‘The job’, wrote Cobby,

‘consisted of getting to the ‘line’ … as fast and often as one could, and letting the enemy on the ground have it as hot and heavy as possible. … All this flying was done under 500 feet and our targets were point blank ones … The air was full of aircraft, and continuously while shooting-up the troops on the ground we would be attacked by enemy scouts … The smoke of the battle below mixed with the clouds and mist above rendered flying particularly dangerous. … On top of this there were scores of machine-guns devoting their time to making things as unpleasant for us as they could.’

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ART08007. H Septimus Power, The incident for which Lieutenant F.H. McNamara was awarded the VC, 1924, Painting: oil on canvas, 143 x 234.7 cm. On 20 March 1917, McNamara, flying on a bombing operation, saw a fellow squadron member, Captain D. W. Rutherford, shot down. Although having just suffered a serious leg wound, McNamara landed near the stricken Rutherford who climbed aboard, but his wound prevented McNamara from taking off and his aircraft crashed. The two men made it back to Rutherford’s plane which they succeeded in starting and, with McNamara at the controls, they took off just as enemy cavalry reached the scene.

Such flights were both dangerous and exhausting. ‘I always emerged from them almost rigid with tension,’ commented Cobby. Nevertheless, they must have given pilots and observers the feel of an even contest. In September 1918, with the Turkish armies in full retreat, No.1 Squadron had a very different experience of attacking men on the ground.

On the morning of 21 September, British and Australian bombers discovered the main Turkish column passing through a gorge on the Wady Fara road. Having bombed the lead vehicles, trapping those behind on the narrow road, the airmen proceeded to destroy as many of the Turks as they could. Clive Conrick, an observer in No.1 Squadron, described the slaughter as he turned his machine guns on the trapped men below, many of whom sought to escape by climbing the cliffs above the road. Flying almost parallel to the fleeing men Conrick was close enough to see,

'chips of rock fly off the cliff face and red splotches suddenly appear on the Turks who would stop climbing and fall and their bodies were strewn along the base of the cliff like a lot of dirty rags. When Nunan [his pilot] was climbing again to renew his attack, I had a better opportunity to machine gun the troops and transports on the road.'

As the attacks continued throughout the day, the Turkish survivors waved white flags. ‘But,’ wrote Conrick, ‘it was quite impossible for us to accept the surrender of the enemy, so we just kept on destroying them.’ Another No.1 Squadron observer, L. W. Sutherland, called it ‘sheer butchery’.

At the same time Sutherland recognised that he was witnessing a significant moment in the wartime use of aircraft. ‘A vitally important duty had been given to us,’ he wrote. ‘For the war, we, the newest arm of the service, had the most onerous work in a major operation. We were not going to fall down on our job. But oh, those killings! ... Only the lucky ones slept that night.’ Such one-sided encounters were relatively rare. Experiences like those of Cobby on the Western Front were more typical.

In an age when few had flown, many men found that flying could be fun. Donald Day, formerly of the Australian Army Medical Corps, became a pilot in May 1918. He transferred to the AFC too late to fly on operations and remained in England until the armistice, but he appreciated the joy that flying could bring:

One of the finest experiences of flying is to closely examine the large fleecy white clouds. They contain features similar to very rugged country gullies, hills etc. In places the gully turns sharply, too much so for a turn, and into cloud one goes; no cloud with sun shining, the shadow of the machines may be seen surrounded by a complete rainbow halo.

Even the more reserved Lewis was able to appreciate the beauty of flying. On a bumpy flight one morning in February 1918 his nausea gave way to delight as his pilot broke through the clouds. ‘It was extremely beautiful. On one occasion we flew round a balloon which was over Ypres and we both waved to the balloonatic who answered in a like manner.’

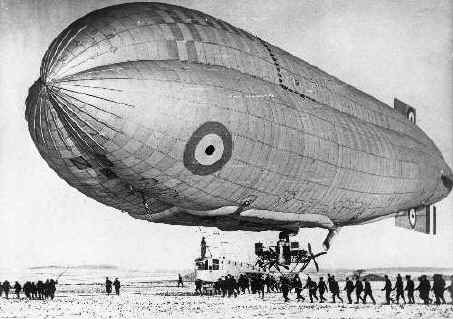

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM H12101. Aerial observation airship. These balloons made manned observation flights over enemy positions.

Giving young men control of what were then the most high-powered and sophisticated aircraft in production could also lead to mischief. Some pilots in No.1 Squadron devised a game called ‘feluccaring’ on account of its practice of flying around small boats — known as feluccas — in such a way as to make them capsize and sink, leaving the one-man crew to swim ashore. Such a thoughtless tactic, probably a game to the airmen, was unfortunately all too typical of the often racist attitudes of Australian troops to the people of the Middle East.

During the last weeks of the fighting there, No.1 Squadron flew in support of the Allied advance into Palestine, moving from one airfield to another as their armies pursued the retreating Turks northwards. As armoured motor vehicles and cavalry raced to keep in touch with the fleeing Turks during October 1918, the only fighting that continued in the Middle East was in the air. The war against Turkey ended on 31 October 1918. No.1 Squadron returned to Egypt after the armistice and embarked for Australia in January 1919.

The war against Germany lasted only a few days longer. As the German Army on the Western Front retreated eastwards, their airmen continued to fight.

October and early November 1918 were characterised by massive sweeps of Allied aircraft over the German lines. Combats were frequent as air battles continued and Allied airmen bombed and strafed the retreating Germans on the ground. Even on the last day of the war, No.2 Squadron was bombing the Germans while No.4 Squadron flew escort.

After the armistice, No.4 Squadron became the only Australian unit of the British Army of Occupation, entering Germany on 7 December 1918. Each of the Australian squadrons that had served on the Western Front left Europe for home in early March 1919. During the war, 460 officers and 2234 men served in the AFC and 178 had been killed. By the standards of the First World War these casualties were light. The AFC was a pioneering corps, laying the groundwork for the Royal Australian Air Force and making a significant contribution to Australian civil aviation, through the efforts of men such as Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, MC, Sir W Hudson Fysh KBE, DFC, (the founder of QANTAS) and the brothers, Captain Sir Ross Smith KBE, MC, DFC, AFC., and Lieutenant Sir Keith Smith KBE.

Text and images reproduced with the kind permission of the Australian War Memorial. For additional information and recommended reading go to: http://www.awm.gov.au/atwar/ww1_flying.htm