The WW1 Nurses

by Roslyn Bell

One of the least publicized of all Army services is the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps, which has given more than 100 years of dedicated work to caring for Australian servicemen in times of war and its aftermath.

The history of the Corps dates back to 1898 when a small nursing service was formed in Sydney. It consisted of one Lady Superintendent and twenty-four nurses. The first actual service of nurses with Australian troops was during the Boer War (1898-1903).

When war broke out in 1914, the Australian Government raised the first Australian Imperial Force for overseas service. The nurses to staff the medical units, which formed an integral part of the AIF, were recruited from the Australian Army Nursing Service Reserve and from the civil nursing profession.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM P02626.002. At sea. c. 1916. Australian nurses take part in a lifeboat drill on HMTKaroola. Many are wearing their life jackets over their long nurses uniforms. The Karoolawas initially used as a troop transport, but on arrival at Southampton, England, she was converted to a hospital ship, with accommodation for approximately 460 patients. As a hospital ship she made numerous voyages between England and Australia.

Senior officers were more inclined to have trained male soldiers in preference to female nurses. Major General Howse, Director of Medical Services, has been quoted as saying that ‘the female nurse — as a substitute for the fully trained male nursing orderly — did little toward the actual saving of life in war … although she might promote a more rapid and complete recovery’. General Howse was speaking at a time when the contribution of the Nursing Service to the treatment of the wounded soldiers, at an early stage, had yet to be recognized by the Australian authorities.

The first draft of Sisters left Australia in September 1914 and throughout the war, the Nursing Service served wherever Australian troops were sent. A number were also sent to British units in various theatres of war.

Australian nurses served in places such as Vladivostok, Burma, India, the Persian Gulf, Egypt, Greece, Italy, France and England. The record of service for these Sisters is outstanding, and one which set a very high standard for all who were to follow. The statistics are noteworthy:

2139 served overseas

423 served in Australia

25 died

388 were decorated

(Seven Military Medals were awarded to Australian Nurses for their courage under fire.)

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM H00232. Abbeville, France. Group portrait of AANS nursing sisters at 3rd Australian General Hospital (3AGH).

An example of one nursing officer’s experience under fire is from her diary from a Casualty Clearing Station at the Western Front:

The noise was so terrific, and the concussion so great that I was thrown to the ground and had no idea where the damage was. I flew through the chest and abdo [abdomen] wards and called out: ‘are you alright boys?’

‘Don’t bother about us,’ was the general cry.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM P02523.004. Two members of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) with patients in Victoria War Hospital, Bombay.

All the hospitals’ lights were out and there was a faint moon, but the sky overhead was full of searchlights and fragments from the bursting anti-aircraft artillery. I passed the cook running for an adjacent paddock, swearing hard and complaining that the bombs had put his fire out.

Running on, she suddenly fell headlong into a bomb crater …

I shall never forget the awful climb on hands and feet out of that hole that was about five feet [1.5 metres] deep with greasy clay and blood (although I did not know then that it was blood).

She raced back to the tent and was shortly joined by the badly shaken Padre, who went off to get help — after urging her to take cover. She ignored the advice and again tried to get into the tent. Grabbing hold of a handle under the fly, she tried to drag a stretcher free. The patient was dead, and the splintered handle came away in her hand, throwing her backwards into the crater again.

I cannot remember what came next, or what I did, except that I kept calling for the orderly to help me and thought he was funking, but the poor boy had been blown to bits. Somebody got the tent up, and when I got to the delirious pneumonia patient, he was crouched on the ground at the back of the stretcher. He took no notice of me when I asked him to return to bed, so I leaned across the stretcher and put one arm around and tried to lift him in. I had my right arm under a leg, which I thought was his, but when I lifted I found to my horror that it was a loose leg with a boot and a puttee on it. It was one of the orderly’s legs which had been blown off and had landed on the patient’s bed. The next day they found the trunk [torso] about 20 yards [18 metres] away.

To put into some perspective the workloads and consequent stresses these nurses endured, consider:

- During the First World War, a one thousand-bed hospital in Cairo — completely under tentage, without any floor covering — was staffed by one matron, 15 Sisters and 30 staff nurses.

- In 1917, in France, one of the hospitals had to be extended to 2000 beds during a ‘heavy rush’.

Acting under such adverse conditions, these women proved themselves to be of awesome dedication.

Sister Alice Ross-King, ARRC, MM

from Just Soldiers by Darryl Kelly

One such lady who was truly worthy of the title ‘front-line angel’ was Alice Appleford (nee Ross-King).

Sister Alice Ross-King ARRC, MM. (Photograph courtesy Mark Appleford)

Alys Ross was born in the Victorian town of Ballarat, in August 1891.1 She was of hardy Scottish stock and while she was still a toddler, her father had moved the family to Perth in search of a better life. Following a tragic fishing accident which claimed the lives of her husband and two sons, Mrs Ross returned to Melbourne with her daughter.2

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM J05886. Australian officers and nurses enjoying a picnic at the ‘Spinney’, Ismailia, Egypt.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM H12939 Alexandria, Egypt, 1915. Wounded from Gallipoli being transferred from hospital ship Gascon to trains for transfer to hospital in Cairo.

Alys attended some of the finer Melbourne schools for young ladies and from an early age decided on a career in nursing. She started her training at the Alfred Hospital and remained there until she completed her Certificate in Nursing. As Sister Alys Ross she continued at the hospital, where she added to her qualification, that of a theatre sister, and at times was called upon to fill the position of acting matron.1

With the onset of war, Sister Ross enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in November 1914. 3

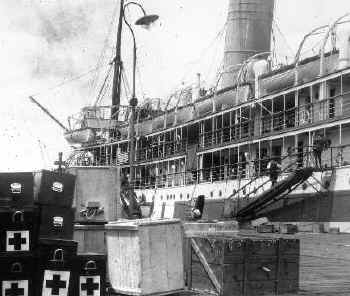

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM P00356.003. Medical supplies waiting to be loaded aboard hospital ship Kyarra, 1914.

During her AIF service she used the surname Ross-King and changed the spelling of her Christian name to Alice. Her mother was extremely upset with her daughter’s decision to go to war. Alice was all the family she had left and the thought that her only child might be killed or injured weighed heavily on Mrs Ross’s mind.

Alice was allocated to the 1st Australian General Hospital (AGH) and sailed for Egypt on 21 November 1914 aboard the hospital ship Kyarra.4 The 1st Australian General Hospital was based in the Cairo suburb of Heliopolis and the nursing staff was kept busy with a constant stream of patients emanating from the AIF desert training camps at Mena.

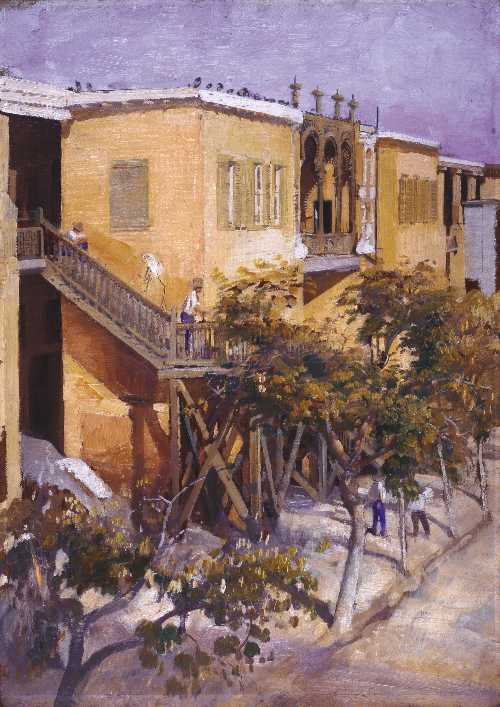

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM ART02817. Lambert, George, Courtyard, 14th Australian General Hospital, Abbassia,1919, Painting: oil with pencil on wood panel, 45.5 x 32.3 cm. Courtyard of hospital seen from balcony of a ward. Convalescent patients under trees and on stairs; nurse on stairs. 14AGH was housed in an Army barracks.

It wasn’t all work in those early days in Egypt, and the nurses enjoyed an active social life. They hosted afternoon teas on the lawns of their quarters and they were always the first to be invited to the dances at the various officers’ messes dotted around Cairo.

With the imminent departure of the 1st Division to Gallipoli, it was decided to prepare other hospital facilities in anticipation for the expected tide of wounded soldiers. Alice, along with a number of other nurses, was detached to the nearby city of Suez, where they were tasked to prepare suitable buildings to be used as clearing stations for Gallipoli casualties.5

Their worst fears were realised when, in late April 1915, the first of the wounded from the Gallipoli beachhead reached the wards. Alice and the other dedicated nursing staff worked around the clock, tending to their patients and fighting overwhelming odds to improve the survival prospects of many of the most seriously wounded. Sometimes they were successful. Other times they had to face the heartbreaking reality that their best efforts had failed. To those in their care they were truly front-line angels.

It was decided that some of the more gravely wounded would be returned to Australia — to make room for others of the increasing number of casualties. As the wounded would need nursing care during their voyage home, it was necessary for some of the nurses to accompany them to provide ongoing treatment during the trip. Sister Ross-King was amongst those chosen to return to Australia.1

Alice was aware that a shortage of nursing staff at home might jeopardise her chances of returning to the front. Immediately after she landed in Australia, she sought to secure orders to be sent back to Egypt. She enjoyed a short leave with her mother before again bidding her a tearful good-bye.

In April 1916, Sister Ross-King helped establish 1AGH in France.5 The hospital was based in Rouen and the medical staff quickly prepared themselves for the onslaught of casualties from the ‘real’ war. They didn’t have to wait long — actions at Fromelles in the north and Pozieres on the Somme kept the hard-pressed nurses working around the clock.

Ross-King remained at 1AGH Rouen for the duration of the Somme offensive then joined the 10th Stationary Hospital at St Omer in the north of France. In July 1917, Alice was moved forward to the 2nd Australian Casualty Clearing Station which was situated close to the battlefront near Trois Arbres.5

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM E04623. France, 30 November 1917. A ward in 2nd Casualty Clearing Station, St. Omer, France. Most of the patients treated were wounded in the fighting of the Third Battle of Ypres.

One night — only five days after her arrival — Alice was making her way back to her tent at the end of her shift. As she followed a young orderly along the duckboards, she heard the high-pitched sound of approaching aircraft. Staring skyward, she could see the grey outline of the planes and as they came closer she could distinguish the bold crosses on the wings.

She knew that the hospital was clearly marked with large red crosses but, despite this, the German pilots seemed hell-bent on attacking. She heard the whistle of falling bombs just before one of the missiles exploded directly in front of her, knocking her to the ground. Regaining her senses, Alice looked around for the orderly but could not see him. Realising the enormity of the situation, she rushed back to her patients.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM H01993. St. Omer, France, 2nd Casualty Clearing Station tent lines, 12 kilometres from the town.

The deadly projectiles were now bursting amid the buildings and tents. As she ran to the wards, she found what was left of the pneumonia ward tent. The extract in her diary reads:

Though I shouted, nobody answered me or I could hear nothing for the roar of the planes and artillery. I seemed to be the only living thing about.

During the ensuing hours, Alice’s actions were inspirational. Little did she know that her work on that terrible night would result in her being awarded the Military Medal, ‘for great coolness and devotion to duty’.6

By now, the AIF was locked in the Third Battle of Ypres and the casualty clearing station was filled to capacity with wounded Diggers. The doctors and nurses worked tirelessly as the sheer volume of casualties and the severity of their wounds taxed the medical staff to their limits. Alice wrote:

The Last Post is being played nearly all day at the cemetery next door to the hospital. So many deaths … 5

In November 1917, Alice returned to Rouen where she was promoted to Head Sister, 1AGH. Accompanied by a number of other sisters and nurses, Alice moved to an advanced dressing station just behind the front lines. The stream of incoming wounded seemed endless and the days were long and tiring. After one such shift, when they had finally gained the upper hand, the doctor said, ‘That’s the lot for now, Sister. Why don’t you get some sleep while you can?’

As she made her way back to her tent, she heard the feeble, anguished moans of wounded men. She searched until she found the source—53 badly wounded German prisoners who had been all but forgotten for the past three days. ‘Doctor! Doctor! Come quickly!’ she called frantically.

Alice’s diary entry summed up the situation that confronted her:

I shall never forget the cries that greeted me. They had gone without food or water … everyone on our staff was dead beat but I got the doctor to come and fix them up. We did forty patients in 45 minutes (the other 13 had died). No waiting for chloroform … amputations and all, and onto the train an hour and a half after I had found them.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 080772. Melbourne 1944. Major A R Appleford, ARRC, MM, Assistant Controller, Australian Army Medical Women’s Service.

Alice was twice Mentioned in Despatches and she was awarded the Royal Red Cross, 2nd Class, in the King’s Birthday Honours of 1918.6

With the cessation of hostilities following the Armistice, Alice returned to England. In January 1919 she boarded a troopship bound for home. It was during the voyage that she met her future husband, Dr Sydney Appleford. The pair married later that year and settled in rural Victoria.

With the onset of the Second World War, Alice Appleford took on the task of training members of the Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) — medically trained but not fully qualified nurses who worked in convalescent hospitals, on hospital ships and in the blood bank, as well as on the home front.

In 1949, Alice was awarded the Florence Nightingale Medal for her considerable efforts in support of the Red Cross and Service charities.5

An extract of the citation sums up this amazing woman:

No-one who came in contact with Major Appleford could fail to recognise her as a leader of women. Her sense of duty, her sterling solidity of character, her humility, sincerity and kindliness of heart set for others a very high example.

Alice Appleford died on 17 August 1968, but her memory lives on in the Alice Appleford Memorial Award, which is presented annually to an outstanding member of the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps.

- Coulthard-Clark C, (Ed.) The diggers: makers of the Australian military tradition, Melbourne University Press, 1993

- Family interview with the author, May 2003

- National Archives of Australia: B2455, WW1 Service Records, Sister A Ross-King MM, ARRC

- AWM 8 Unit Embarkation Nominal Rolls, 1AGH AIF, 1914–1918 War

- Reid R, Just wanted to be there - Australian Service Nurses 1899–1999, Department of Veterans Affairs, Canberra, 1999

- Barker M, Nightingales in the Mud – The Digger Nurses of the Great War, 1914–1918, Sydney, 1989

For more information on the WW1 hospitals and medical facilities visit: http://www.unsw.adfa.edu.au/~rmallett/ then select Part B - Branches Medical.