An overview by Robert Lewis

The year 2004 marks the 90th anniversary of the onset of the First World War. Australia’s support of Great Britain as the ‘Mother Country’ meant that this country was also at war. The information that follows examines the impact this conflict had on the fledgling Australian nation. A range of issues, such as: the male population’s reaction to recruiting drives; Gallipoli, where the national character was tested and found not wanting; the government’s wider range of powers over some aspects of people’s lives; effects on the economy, and the changing role of women has been addressed and enhanced with cartoons, posters and photographs from the time.

Initial reactions

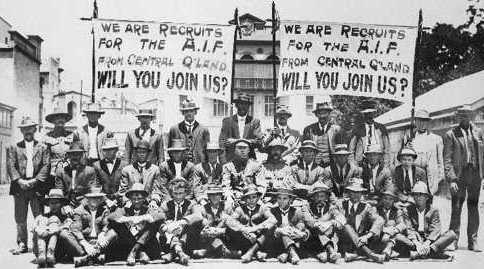

The outbreak of war in August 1914 seemed to unleash a huge wave of enthusiastic support for Britain, and support for Australia’s part in the war. All major political parties, churches, community leaders and newspapers seemed to support Australia’s entry. It was seen as a moral and necessary commitment. There was a rush to the recruiting offices, and, at this stage, only the very fittest and healthiest men were accepted.

The whole country seemed to be both enthusiastic for the war, and united in support of it. There is, however, some evidence that this is an incomplete and even distorted impression. There are hints and suggestions of the fracture lines in society that would later lead to great bitterness and divisions in Australian society. For example, while many tried to enlist, far more did not. Even during the first enlistment rush, there are stories of white feathers being sent, and women rejecting and abusing men who did not enlist. There were also some who actively opposed Australia’s entry into the war, though their voice seems to have had few ways of being heard at the time.

Gallipoli

The landing at Gallipoli was a major event in the war. Even though the Gallipoli campaign was a military defeat, it helped to provide Australians with a new sense of their identity and place in the world. One reason is the fact that the landing was a separate action in the war. It was not swallowed up in the general war news. People in Australia knew their boys were training for their ‘baptism of fire’ and when it came the Australians were an identifiable body of troops. So what happened was able to be isolated and analysed as an action by Australians.

The reporting of the landing also influenced people’s reactions to the event. The glowing tribute of the British war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett gave the achievement an authenticity -- here was someone who should know who was making such a positive and favourable judgement. Another reason for the reaction in Australia is the possibility that most people in Australia had some connection with the men of the first AIF who landed at Gallipoli. Death notices on the first anniversary were sent not only by parents, husbands, sisters and sons and daughters -- but also friends, cousins, work mates, fellow church members, and families of soldier mates. The ripples of those directly affected by the landing spread throughout much of Australian society.

Australia had been a nation for just 14 years, and there was an uncertainty about how they would measure up as a race against the people who had founded them, the British. There was also a belief in society that war was a testing ground for individual and national character. Australians had been brought up on the glories of British military exploits. They were now part of that picture, and were able to match themselves against the best in the ultimate test. In the words of one contemporary, ‘They had been tested, and not found wanting’. So Gallipoli was a great sigh of relief that the test had been passed, an affirmation of their national worth.

In the 1970s and 1980s in particular some commentators challenged the strength or relevance of the ANZAC legend, arguing that it had little relevance to women, to a multicultural Australia, and to an era when a military heritage was tarnished by widespread anti-Vietnam War feeling. Such criticism seems to miss the point. The ANZAC legend does not have to mean that any individual could be an ANZAC, but that the ANZACs represented the values and behaviour and qualities of the whole society -- and the ANZAC qualities of bravery, perseverance, mateship, determination and all the other positive aspects that can be found in the story are still what we would show if we were tested again.

Deaths and casualties

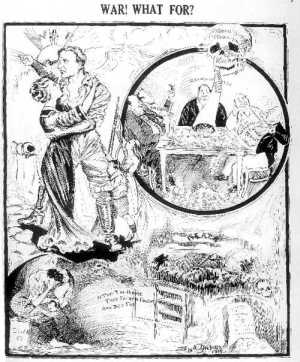

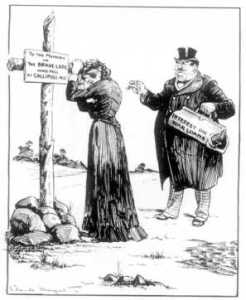

Sign says: 'To the memory of the brave lads who fell at Gallipoli, 1915' Man's bag says: 'Interest on War Loans'

After the retreat from Gallipoli, most Australian soldiers eventually became involved in the trench warfare of the Western Front. Despite repeated attempts, little ground was won and kept between 1916 and 1918. The war became one that had to be grimly endured, and the first flush of enthusiasm for the war and the thrilling achievement at Gallipoli soon led to a more harsh and realistic attitude towards war as, over time, the death and casualty lists increased.

Recruiting

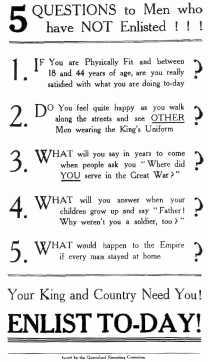

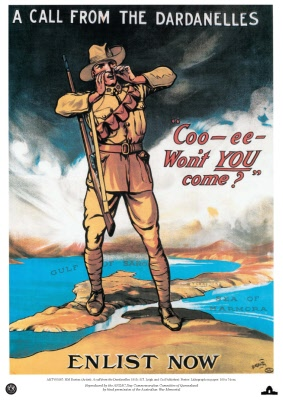

Continued casualties led to great recruiting campaigns. The strongest believers in the war could not understand how others in society might not share their attitude that the war demanded every person’s full and total commitment. Nothing else was of any importance until the war was won.

Others, however, believed that there were other priorities that still should be pursued -- particularly when the economic costs of the war pushed wages down and prices up. These people believed that the war was being fought for a particular way of life -- and it was patriotic to maintain that way of life during the war.

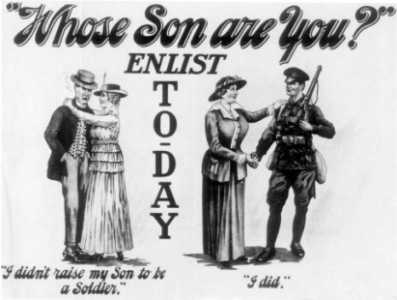

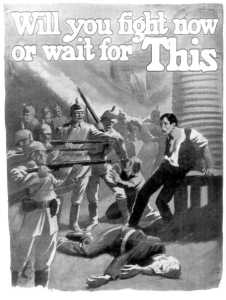

The ‘patriots’ tried to gain recruits for the war. There were two ways in which this could be done: by ‘persuasion’, or by ‘force’. ‘Persuasion’ involved appealing to the individual’s sense of what was right and wrong to do in the circumstances; ‘force’ involved accusation, confrontation and guilt.

One of the main divisive figures of the war was Norman Lindsay. Many of his posters encouraged hatred of the enemy, or confrontation between groups of Australians, or both.

Government powers

The war saw governments take on new and wide powers over aspects of people’s lives. The Commonwealth Government was the great ‘winner’ from the war. Running a war was a national event, and it became clear that the Commonwealth would need to increase its authority as well as its spending and revenue-raising powers to prosecute the war successfully and effectively. One of its major actions was to pass the War Precautions Act. The Act gave the Commonwealth great jurisdiction -- powers that were far greater than it would have under peace conditions.

The War Precautions Act gave the Commonwealth Government weight in two main areas. It could make laws that were normally not within its prerogative -- so in effect the Constitution which normally limited the Commonwealth’s power was suspended for the duration of the war and six months afterwards. The War Precautions Act and the Defence Act gave the Commonwealth authority to make laws about anything that affected the war effort -- and High Court interpretations in disputes meant that this covered almost anything. In a famous quote, a member of parliament asked the Commonwealth’s main law officer, the Solicitor-General Sir Robert Garran, ‘Would it be an offence under the War Precautions Act …?’ ‘Yes!’ said Garran.

The other great change was that many of these new powers available to the Commonwealth were able to be exercisable under Regulation, meaning that parliament did not have to pass the law, all it required was a document prepared by the relevant Minister, and signed by the Governor-General. So in effect parliament lost much of its control during the war, and laws were made by a few Ministers.

Some of the major activities carried out under the authority of the War Precautions Act by the Commonwealth were:

- passing Trading With the Enemy Acts that cancelled existing commercial contracts with firms in enemy countries;

- creating loans to raise money for the war;

- taking on power to tax incomes -- they shared this with the States, who previously had this power for themselves;

- fixing the price of many goods -- something that the Constitution did not give the Commonwealth the prerogative to do normally;

- interning (locking up) without trial people who were born in or had an association with enemy countries;

- compulsorily buying farmers’ wheat and wool crops; and

- censoring publications and letters.

Economy

The war had a great effect on the Australian economy, and the repercussions of these changes were mixed. One of the earliest impacts of the war was the government’s cancellation of existing trade agreements with Germany and Austria-Hungary. As a result, Australian firms in industries such as steel-making and pharmaceuticals suddenly found themselves taking up contracts that had previously been filled by German rivals -- and fortunes were suddenly available to firms such as BHP and Nicholas.

The government was keen to make sure that Australian wheat, wool and meat reached Britain and helped the war effort there. So it passed a law giving it the power to compulsorily acquire the whole wheat and wool harvests -- an impossible action under the Constitution, but able to be done under the War Precautions Act.

However, shortages and war profiteering (selling scarce goods at a very high price) meant that many ordinary working people suffered a fall in their purchasing power, and their standard of living. This led to a series of major strikes in the major cities. To finance the war the Commonwealth had a series of war loans, and then peace loans. All were over-subscribed. This seemed to some to be further evidence of the inequality of sacrifice in the war -- those with money to spare could actually profit from the war, while others were suffering economic loss and decline.

The war provided a form of protection to Australian industries -- removing competition. By the end of the war more than 400 products were being produced in Australia which had not been produced here before the war.

Conscription

In 1916 Prime Minister Hughes proposed raising the numbers needed to maintain Australian troops at full strength at the Front by conscripting those who to date were unwilling or opposed to enlisting to fight. The government already had the power under the existing provisions of the Defence Act to conscript men -- but only for service in Australia. They could not be sent overseas to fight.

All the government needed to do was to change the Defence Act to extend the existing power of conscription from home service, to overseas service. All it had to do to achieve that change in legislation was to pass an amendment through both houses of parliament -- the Senate, and the House of Representatives.

But there was a problem. Some members of the Labor Government were against conscription. Hughes knew that he had enough supporters of conscription among the Labor and Liberal parties to have a majority in the House of Representatives; but he was a few short of a majority in the Senate.

To overcome this problem Hughes decided to hold a national vote on the issue. This vote is sometimes called a referendum, and sometimes called a plebiscite. Strictly speaking a referendum is a vote to change the Constitution. There was no need to change the Constitution in this case, as the Constitution already gave the government power to introduce conscription. So the vote was in effect a national ‘public opinion poll’ on the issue. The vote would not mean anything officially -- but what Hughes planned was that he would be able to use the public vote in favour of conscription to persuade a few Senators to change their vote in parliament. Even though the Senators were personally against it, the vote would show that the people they represented in fact wanted conscription, so the Senators would accept the people’s wishes. That was the theory.

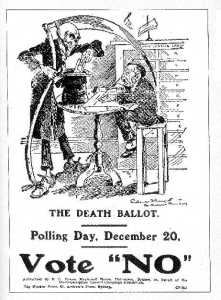

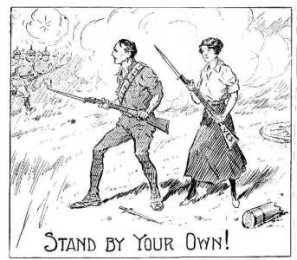

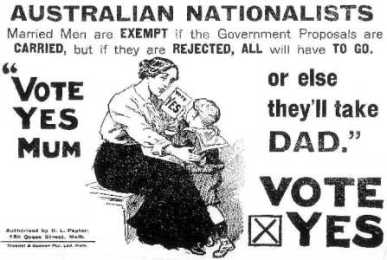

The supporters and opponents of conscription started campaigning vigorously on the issue. The campaign literature of each side was often bitter and divisive. Each side presented its argument as the moral and loyal thing to do, while the other’s approach would be disastrous.

The vote was very close -- with conscription being rejected 51 to 49 per cent. Many commentators asked why conscription was rejected. A better question may be, why was the vote so close?

focus for a lot of different points of view about the war. Some people opposed the war; others were opposed to conscription as a principle; some were saying that they were hurt by the economic situation of the war, and were protesting against that; still others were voting to protect unionism; and there were those who were protesting at the British treatment of the rebels in Ireland. Normally these people might not have agreed with each other on many things, but they all agreed on the conscription question, and the issue gave them all a chance to express their opposition.

In 1917 Hughes held another vote on the issue. This time he actually had a majority in both Houses of Parliament, and did not need the vote. He wanted, however, to give the people another chance to overcome what he saw as their great mistake in rejecting conscription the previous year -- a chance to redeem themselves. The campaign was again bitter and divisive, and conscription was again defeated, this time by a slightly larger margin.

Easter uprising

One of the elements that influenced many people’s reaction to the war was the Easter Uprising in Ireland. Ireland was under British control, but many Irish were nationalists -- they wanted Ireland to be its own country. On Easter Sunday 1916, a group of IRA rebels seized buildings in Dublin as the start of an uprising. The British troops there quickly defeated the rebels. Many were taken prisoner, tried, and executed.

Many Australians had strong ties to Ireland, and there was also a strong connection between the Roman Catholic religion and Ireland -- many of the Church’s priests, nuns and teaching staff were Irish born. The Archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix, was particularly staunch in his condemnation of the brutal British suppression of the rebellion, and he increasingly distanced himself from support of the war -- influencing many of his flock to do the same. But it is not accurate to say that Australia became divided along religious and ethnic lines -- Protestant British versus Irish Catholics -- as there were important religious leaders, particularly Archbishop Kelly of Sydney, who did not support the Irish uprising.

Political change

The war led to great changes in political life.

In 1914 the Liberals were in power, but were defeated at the general election that was under way at the outbreak of the war. The Australian Labor Party became the Government, with Andrew Fisher, and then from 1915 William Morris Hughes as the Prime Minister.

Hughes, a Welsh immigrant as well as a Labor member, enthusiastically supported Australian involvement in the war, and saw himself as responsible for making sure that Australia fulfilled its role as part of the Empire. By 1916 he was convinced that the great losses being suffered on the Western Front could not be met by voluntary recruiting, and that those men who were not ‘doing their duty’ needed to be conscripted into the fight. This caused great division within the Labor Party.

After the defeat of the first Conscription Referendum, Hughes and a number of others left the Labor party, and joined with the Liberals to form a new Nationalist party, determined to do everything possible to win the war. This new Nationalist party became the government for the rest of the war.

Hughes’ pro-war enthusiasm led him into conflict with one of his strongest critics -- the Queensland Australian Labor Party Premier, T. J. Ryan. Ryan did all he could to defeat conscription -- and in doing so clashed with Hughes. In one famous incident at Warwick Station, Hughes was hit by an egg thrown by an anti-conscription protester. Hughes felt, probably correctly, that Ryan did nothing to stop the incident or to track down the protester, so Hughes created the Federal Police to pursue Commonwealth matters! In another incident, Hughes had banned certain anti-conscription material, but Ryan had the material reproduced in Queensland’s Hansard, the record of parliamentary proceedings, and exempt from normal censorship.

War weariness

By 1917 and 1918, people were increasingly war-weary. The deaths and casualties mounted; there seemed to be no substantial victories; the war seemed to be at a stalemate; the economic costs of the war continued to hurt many in the community; recruits now only trickled in where they had flowed in 1915 and 1916.

Women’s role

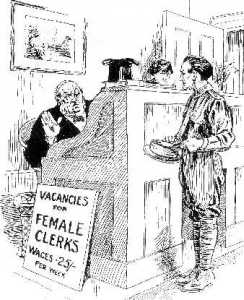

At the outbreak of war far fewer women than men participated in work, and these tended to be in lower-paid occupations. Women’s main role was seen to be in the home. The withdrawal of about half a million men most of whom had been in the workforce did not, however, result in their direct replacement by women.

Women’s contribution to the workforce rose from 24 per cent of the total in 1914 to 37 per cent in 1918, but the increase tended to be in what were already traditional areas of women’s work -- in the clothing and footwear, food and printing sectors. There was some increase also in the clerical, shop assistant and teaching areas. Unions were unwilling to let women join the workforce in greater numbers in traditional male areas as they feared that this would lower wages.

Top: Sewing rabbitskin vests and shirts for the Australian Comforts Fund, Melbourne Town Hall. Below: Canned goods collected by New South Wales children being sorted by Red Cross volunteers.

Many women sought to become more involved in war-related activities -- such as cooks, stretcher bearers, motor car drivers, interpreters, munitions workers -- but the government did not allow this participation.

A number of women’s organisations did become very active during the war -- including the Australian Women’s National League, the Australian Red Cross, the Country Women’s Association, the Voluntary Aid Detachment, the Australian Women’s Service Corps, and the Women’s Peace Army.

One of the most active groups was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which succeeded in having hotel hours restricted in several States.

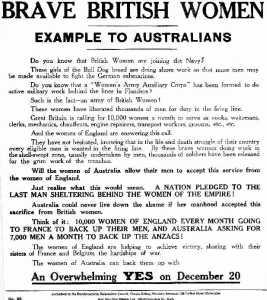

Many women were also actively involved in encouraging men to enlist, and were often used in recruiting and pro- and anti-conscription propaganda leaflets.

Oral history. We began hearing a lot about 'the war effort' and people stopped saying the war would be over in six months, or even a year. Whenever I came home from school, the house was full of women clicking knitting needles and manipulating dark wool, and making huge quantities of socks, vests, mittens and mufflers, as well as sewing pyjamas and shirts. Mum ran Red Cross classes with first aid and bandage rolling … Mum, who was a leading light in the CWA (Country Women's Association) as well as the Red Cross, spent more and more of her time on the war effort... Nora Pennington, the good little girl who had written the composition about Gallipoli, was the school's champion sock knitter. At lunchtime and recess she sat with her ankles neatly crossed and her boots buttoned, turning the heels of the socks very prettily. She eventually won the district record for the number of socks, mufflers, mittens and balaclava helmets knitted by anybody under the age of thirteen; her father made sure that the news reached the front page of his paper, with the heading 'LITTLE NORA DOES HER BIT'. The rest of us longed to grab her knitting, rip the stitches out and snarl the wool for her. David Gleason in Jacqueline Kent, 'In The Half LIght', Doubleday Sydney 1988 pp56-58

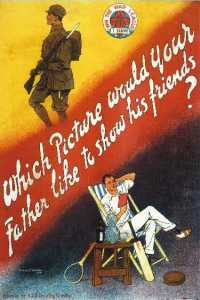

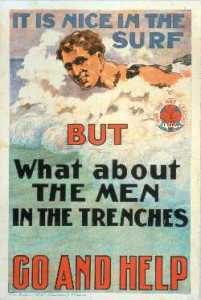

Sport

During the war there were many calls for normal entertainments such as competitive sport to be abandoned. This was mainly because it was felt that the continuation of sport distracted people’s attention from the serious business of the war -- and also because competitive sport seemed to be a flaunting by eligible young men of the fact that they had not volunteered to fight. It was a sign of less than total commitment to the war. Amateur sports did tend to stop for the duration, but the semi-professional football competitions continued.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

‘The enemy within’

This was the phrase often used to describe ‘enemy aliens’ -- non-naturalised residents of Australia who had been born in countries that were now the enemy. The 1911 census showed that there were 33,381 German-born residents in Australia, most of whom lived in South Australia and Queensland. These German citizens had to register at local police stations. However, the war caused many Australians to turn against their German neighbours, even though they may even have been naturalised and had sons fighting in the AIF. This hostile attitude was sometimes the result of jealousy, but was also encouraged by the crude official anti-German propaganda. Local authorities also often trampled on the human rights of these people with unjustified searches, surveillance and arrest. 4500 ‘Germans’ were interned during the war, 700 of whom were naturalised and 70 Australian born. At the end of the war, 6150 Germans and other enemy alien nationals were deported. However, the majority of German nationals living in Australia managed mostly to escape public notice and persecution.

The ‘Butcher’s Bill’

The fighting in World War 1 ended at 11am on 11 November 1918. But the deaths and suffering did not end then. To soldiers at the time, the casualties were referred to as the ‘butcher’s bill’. More than eighty years later the cost of the war is still with us -- the butcher’s bill is still being paid.