by Paul Jordan

In April 1995 members of the Australian Defence Force Medical Support Force, a component of the Australian Contingent of the United Nations Assistance Mission For Rwanda (UNAMIR) were deployed to the Kibeho displaced persons’ camp. The camp had been surrounded by two battalions of Tutsi troops from the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), which regarded it as a sanctuary for Hutu perpetrators of the 1994 genocide. In the ethnic slaughter that followed, the RPA killed some 4000 of the camp’s inhabitants. The following article is an edited version of an eyewitness account of the massacre at Kibeho.

It was 5.00 p.m. on Tuesday, 18 April 1995, when 32 members of the Australian Medical Force (AMF) serving in Rwanda received orders to mount a mercy mission. Their task was to provide medical assistance to people who were being forced to leave what was then the largest displaced persons’ camp in Rwanda. This camp was situated some five hours west of the capital city of Kigali, close to the town of Kibeho, and was estimated to hold up to 100,000 displaced persons. I was a member of that Australian force deployed to Kibeho, which comprised two infantry sections, a medical section and a signals section. We left Kigali around 3.00 a.m. on Wednesday, 19 April, travelling through Butare and on to Gikongoro, where the Zambian Army’s UNAMIR contingent had established its headquarters. We arrived at Zambian headquarters at around 7.30a.m. and established a base area before continuing on to the displaced persons’ camp at Kibeho, arriving around 9.30 a.m. The camp resembled a ghost town. We had been told that the RPA intended to clear the camp that morning and our first thought was that this had already occurred -- we had arrived too late.

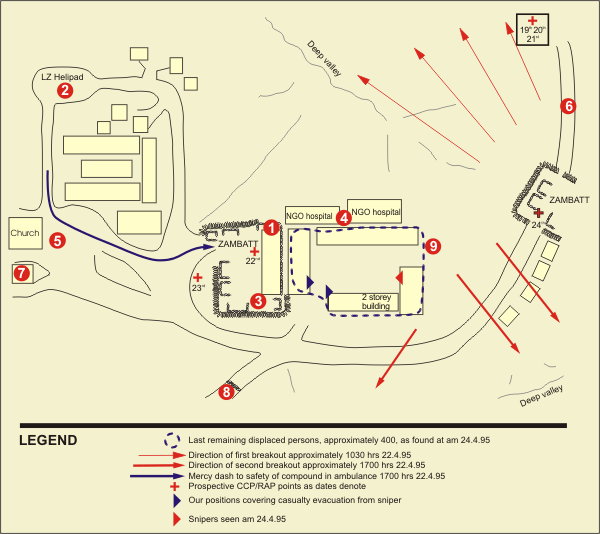

Map depicting events

Woman surrendered then executed in cold blood

Ambulance closely grazed by two bullets shot at lone displaced person

ZAMBATT (Zambian Battalion) latrines -- displaced persons found hiding inside

Triage area -- machete victims -- Saturday am 22.4.95

Highest ground in immediate area

RPA screening and processing -- displaced persons’ exit point for general evacuation

Beginning RPA accommodation

Our entry point each day and RPA roadblock

Recoilless rifle set up am 24·4·95

General information

- Map drawn 1500 hrs 28·4·95 Tpr JGS Church

- Distance from church eastern side to RAP far western side = 1000m

- Distance as seen extreme north to south 600m

- Whole area dotted with lean-tos and grass bivouacs

- All buildings and roads are on high ground

- The valleys either side are quite deep—up to 80 m at 45° angle

As we moved through the camp, we saw evidence that it had been cleared very quickly. The place was littered with the displaced persons’ belongings, left behind in the sudden panic of movement. It wasn’t until we moved deep into the camp that we found them, thousands of frightened people who had been herded closely together like sheep, huddled along a ridgeline that ran through the camp. The RPA had used gunfire to gather and drive these people into a close concentration. In the frenzy of sudden crowd movement, ten children had been trampled to death. As we drove closer, the huge crowd parted before us and people began to clap and cheer: they obviously expected a great deal more from us than we could offer.

We set about the task of establishing a casualty clearing post and, after being moved on twice by RPA soldiers exercising their arbitrary authority, eventually negotiated a position just beyond the documentation area. We spent the day there and saw only one casualty, a UN soldier. We left the camp that day dogged by the frustrating sense of not being needed.

The next day, Thursday 19 April, we arrived at the camp at 8.30a.m. and moved through to what was designated the ‘Charlie Company’ compound, situated in the middle of the camp. Zambian troops on duty in the compound requested medical treatment for a woman who had given birth the previous night, as they thought that she ‘still had another baby inside her’. We arranged for the woman to be medically evacuated by air to Kigali, where it was discovered that she was suffering from a swollen bladder. We set up the casualty clearing post once again at the documentation point and, this time, went out to search for casualties.

RPA troops would frequently resort to firing their weapons into the air in an effort to control the crowd. At around 1.00 p.m., we heard sporadic fire, but could find no casualties. As the day wore on, tension mounted between the displaced persons and the RPA troops. We left the camp that evening amid the echoes of bursts of automatic fire. Leaving the camp was no easy feat because of the RPA roadblocks. We decided to follow a convoy carrying displaced persons out of the camp, but were held up when one of the convoy’s trucks became stuck in thick mud, blocking the exit road. Eventually we extricated ourselves and found a safe route out. Half an hour or so into our journey, we encountered a UNICEF official who informed us that he had received a radio message reporting that ten people had been shot dead in the camp. Because AMF personnel were not permitted to stay in the camp after dark, there was nothing we could do. We had no choice but to continue on to our base at Zambian headquarters.

On Friday, 20 April, we arrived in Kibeho at around 8.30 a.m. to find that thirty people had died during the night. Although the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) hospital was busy treating casualties, we were told our assistance was not required at this stage. We set up the casualty clearing post at the documentation area (for what was to be the last time) and initially treated a few patients who were suffering from colds and various infections. Most of these were given antibiotics and sent on their way. A number of ragged young children appeared and, out of sight of the RPA soldiers, we gave the children new, dry clothes, for which they were most grateful. We also found a man whose femur was broken and decided to remove him from the camp in the back of our ambulance when we finally left for the night.

That evening, as we were preparing to leave, we received a call for assistance from the MSF hospital. Six ‘priority one’ patients required urgent evacuation. We picked up these casualties, all suffering from gunshot and machete wounds, and prepared them to travel. We called in the helicopter and the patients were flown to a hospital in Butare. The man with the broken femur could not be flown out because the helicopter was not fitted to take stretchers, so we prepared him for an uncomfortable ride in the back of the ambulance.

We returned to the Charlie Company compound where we found a man with a gunshot wound to the lung -- a sucking chest wound. He was in a serious condition. Because night was falling, we decided to evacuate him by road to the hospital in Butare along with the man with the broken femur. This meant negotiating the RPA checkpoints as we left the camp. As we persuaded our way through these checkpoints, Captain Carol Vaughan-Evans and Trooper Jon Church (Captain Carol Vaughan-Evans was the Officer Commanding the Casualty Collection Post, Kibeho, at the time. Trooper Jonathan Church, SASR, died in the Blackhawk accident in 1996.) crouched in the rear of the ambulance, giving emergency treatment to the two patients.

We continued our journey accompanied by two military observers from Uruguay who were guiding us. We made steady progress for the next two hours until our front and rear vehicles became bogged. As efforts continued to recover the vehicles, Lieutenant Tilbrook (Lieutenant (now Captain) Steve Tilbrook is currently serving with the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment.) decided to send the ambulance to the hospital as the patient with the chest wound was deteriorating. The two military observers were to accompany the ambulance. After a further hour and a half on the road, and with additional help from Care Australia, the patient was eventually handed over to the MSF hospital in Butare.

On Saturday, 22 April, we arrived at the camp to be told that the hospital was teeming with injured patients, but the MSF workers were nowhere to be found. We went to the hospital where the situation was absolutely chaotic. We saw about 100 people who had either been shot or macheted, or both. Their wounds were horrific and there was blood everywhere. One woman had been cleaved with a machete right through her nose down to her upper jaw. She sat silently and simply stared at us. There were numerous other people suffering from massive cuts to their heads, arms and all over their bodies. We immediately started to triage as many patients as possible, but just as we would begin to treat one patient, another would appear before us with far more serious injuries.

As we worked, we were often called upon to make snap decisions and to ‘play God’ by deciding which patients’ lives to save. We were forced to move many seriously injured victims to one side because we thought they would not live or because they would simply take too long to save. Instead, we concentrated on trying to save the lives of those people who, in our assessment, had a chance of survival.

At one point, an NGO worker took me outside the hospital to point out more casualties. There I discovered about thirty bodies, and was approached by a large number of displaced persons with fresh injuries. Jon Church and I were deeply concerned and returned to the hospital to triage patients. In amongst triaging priority one patients, Jon drew my attention to the patient he was treating. This man had a very deep machete wound through the eye and across the face. I saw Jon completely cover the wounded man’s face with a bandage. There was no danger that the patient would suffocate since he was breathing through a second wound in his throat. The wounded man was, however, very restless and difficult to control, and eventually we were forced to leave him, despite our belief that he would almost certainly die. Later that day he was brought to us again, his face still completely covered in a bandage. Whether the man finally survived his ordeal, only God knows.

As Jon and I worked with Lieutenant Rob Lucas (a nursing officer) to prioritise patients, members of the Australian infantry section stretchered them to the casualty clearing post. These soldiers worked tirelessly to move patients by stretcher from the hospital to the Zambian compound, which had become a casualty department. Meanwhile, the situation at the hospital was becoming increasingly dangerous, and we were ordered back to the compound. Some of the MSF workers had arrived by now and were trapped in the hospital. Our infantrymen went to retrieve them and bring them back to the safety of the compound. As our soldiers moved towards the hospital, they came under fire from a sniper within the crowd of displaced persons. The infantry section commander, Corporal Buskell (Corporal (now Warrant Officer Class 2) Brian Buskell is currently posted to the Royal Military College, Duntroon.), took aim at the sniper, and the latter, on seeing the rifle, disappeared into the crowd.

Our medical work continued unabated in the Zambian compound as the casualties flowed relentlessly. At about 10.00 a.m., some of the displaced persons attempted to break out and we saw them running through the re-entrants. We watched (and could do little more) as these people were hunted down and shot. The RPA soldiers were no marksmen: at times they were within ten metres of their quarry and still missed them. If they managed to wound some hapless escapee, they would save their valuable bullets, instead bayoneting their victim to death. This went on for two hours until all the displaced persons who had run were dead or dying.

The desperate work continued in the compound as we separated the treated patients, placing the more serious cases in the ambulance and the remainder in a Unimog truck. The firing intensified and the weather broke as it began to rain. We worked under the close security of our infantry as automatic fire peppered the area around us. We continued to treat the wounded, crouching behind the flimsy cover presented by the truck and sandbag wall. At one point, a young boy suddenly ran into the compound and fell to the ground. We later discovered that he had a piece of shrapnel in his lung. We managed to evacuate this boy by helicopter to the care of the Australian nurses in the intensive care unit at Kigali hospital. Every time a white person walks into his hospital room, he opens his arms to be hugged.

The automatic fire from the RPA troops continued; people were being shot all over the camp. When we had gathered about twenty-five casualties, we arranged to have them aeromedically evacuated to a hospital in Butare. While the ambulance was parked at the landing zone, a lone displaced person ran towards us with an RPA soldier chasing him. The soldier maintained a stream of fire at his fleeing victim, and rounds landed all around the ambulance. Jon and I ducked for cover behind its meagre protection. When the RPA soldier realised that some of his own officers were in his line of fire, he checked himself. The displaced person fell helplessly to the ground at the feet of the RPA officers. He was summarily marched away to meet an obvious fate.

It was about 4.00 p.m. by the time we started to load the patients onto helicopters, and, by 5.00 p.m., the job was complete. People began to run through the wire into the compound, and the Australian infantry found themselves alongside the Zambian soldiers pushing the desperate intruders back over the wire. This was a particularly delicate task, as some of the displaced persons were carrying grenades. As the last helicopter took off, about 2000 people stampeded down the spur away from the camp, making a frantic dash for safety. RPA soldiers took up positions on each spur, firing into the stampede with automatic rifles, rocket-propelled grenades and a 50-calibre machine-gun. A large number of people fell under the hail of firepower. Fortunately, at this stage, it began to rain heavily, covering the escape of many of those fleeing. Bullets flew all around, and we made a very hasty trip back to the Zambian compound with the rear of the ambulance full of infantry.

Once back in the compound, we watched the carnage from behind sandbagged walls. Rocket-propelled grenades landed among the stampeding crowd, and ten people fell. One woman, about fifty metres from where we crouched, suddenly stood up, with her hands in the air. An RPA soldier walked down to her and marched her up the hill with his arm on her shoulder. He then turned and looked at us, pushed the woman to the ground and shot her.

As the rain eased, so did the firing. I was standing in the lee of the Zambian building when a young boy wearing blood-soaked clothing jumped the wire and walked towards me. I put my gloves on and the boy shook my hand and pointed to where a bullet had entered his nose, indicating to me that the bullet was still caught in his jaw. We took the boy with us and, given that the firing had died down and darkness had fallen, we put him into the ambulance next to a man with an open abdominal wound, and prepared them for the long journey to hospital by road.

As we left the camp, Jon and another medic saw a small child wandering alone. They made an instant decision to save the child, putting her in the ambulance as well. We then faced the unwanted distraction of a screaming three-year-old girl while we were frantically working on two seriously wounded patients. We knew also that the RPA would search the vehicle and any displaced persons without injuries would be taken back to the camp. I decided to bandage the girls’s left arm in order to fake a wound. The first time we were searched, the girl waved and spoke to the RPA soldiers. So we moved her up onto the blanket rack in the ambulance, strapped her in, and gave her a biscuit. The next time we were searched, the girl just sat and ate her biscuit, saying nothing. The RPA soldiers never knew she was there. After being held up at a roadblock for an hour, the convoy, which included all the NGO workers, made its way out of the camp. All the patients were taken to Butare Hospital, while the little girl was taken to an orphanage where we knew an attempt would be made to reunite her with her mother, in the unlikely event that she was still alive.

We re-entered the camp at 6.30 a.m. on Sunday, 23 April. While our mission was to count the number of dead bodies, Warrant Officer Scott and I went first to look around the hospital. Inside there were about fifteen dead. We entered one room and a small boy smiled then grinned at us. Scotty and I decided we would come back and retrieve this boy. I took half the infantry section and Scotty took the other half, and we walked each side of the road that divided the camp.

On one side of the road, my half-section covered the hospital that contained fifteen corpses. In the hospital courtyard we found another hundred or so dead people. A large number of these were mothers who had been killed with their babies still strapped to their backs. We freed all the babies we could see. We saw dozens of children just sitting amidst piles of rubbish, some crouched next to dead bodies. The courtyard was littered with debris and, as I waded through the rubbish, it would move to expose a baby who had been crushed to death. I counted twenty crushed babies, but I could not turn over every piece of rubbish.

The Zambians were collecting the lost children and placing them together for the agencies to collect. Along the stretch of road near the documentation point, there were another 200 bodies lined up for burial. The other counting party had seen many more dead than we had. There were survivors too. On his return to camp, Jon saw a baby who was only a few days old lying in a puddle of mud. He was still alive. Jon picked the baby up and gave him to the Zambians. At the end of our grisly count, the total number recorded by the two half-sections was approximately 4000 dead and 650 wounded.

We returned to the Zambian compound and began to treat the wounded. By now we had been reinforced with medics and another doctor. With the gunfire diminished, we were able to establish the casualty clearing post outside the Zambian compound and, with extra manpower and trucks to transport patients, we managed to clear about eighty-five casualties. A Ghanaian Army major approached Scotty and I to collect two displaced persons who had broken femurs from another area nearby. We lifted the two injured men into the back of the major’s car. It was then that we noticed all the dead being buried by the RPA in what I believe was an attempt to reduce the body count. The Zambians also buried the dead, but only those who lay near their compound.

We had been offered a helicopter for an aeromedical evacuation. We readied our four worst casualties, placing them on the landing zone for evacuation. The RPA troops came, as they always did, to inspect those being evacuated. At the same time, a Zambian soldier brought us a small boy who had been shot in the backside. The RPA told us that we could only take three of the casualties, as the fourth was a suspect. I argued and argued with an RPA major, but met with unbending refusal. He did tell us, however, that we could take the small boy who we hadn’t even asked to take, so we quickly put the boy into the waiting helicopter. The RPA officer then demanded that one of his men, who had been shot, be evacuated in the helicopter. I tried to bargain with the RPA major. In return for taking his soldier to hospital, I asked that we be allowed to evacuate the fourth casualty. His reply was final: ‘Either my man goes or no-one goes’. It was time to stop arguing.

The majority of patients we evacuated that day were transported on the back of a truck. The pain caused by the jolting of the truck would have been immense, but even this amount of pain was better than death. Jon and I took another load of patients to the landing zone, as they were to go on the same helicopter as the CO and the RSM. To our amazement, we were recalled and watched in frustration as the helicopter was filled with journalists. That day, all our patients left unaccompanied.

Just before our departure that evening, Jon and I were called to look at a man who had somehow fallen into the pit latrine, which was about 12 feet deep. I suppose he thought this to be the safest place. We left the camp at about 5.00 p.m. and spent the night at the Bravo Company position which was only half an hour away.

On Monday, 24 April, we returned to the camp which, at this stage, held only about 400 people. The RPA had set up a recoilless rifle, which pointed at one of the buildings they claimed housed Hutu criminals who had taken part in the 1994 genocide. Throughout the morning we saw displaced persons jumping off the roof of the building and, on two occasions, we saw AK 47 assault rifles being carried. The RPA gave us until midday to clear the camp, at which time they stated that they would fire the weapon into the building. We knew this would kill or injure the vast majority of those left in the camp.

Meanwhile the Zambians were busy digging two men out of the pit latrines. They were quite a sight when they were pulled out. The Zambian major planned to sweep through the building and push people out, and wanted us to bolster his ranks. Obtaining permission from headquarters to help the Zambians proved something of an ordeal, to my mind, the result of a surfeit of chiefs. Consequently, we were a crucial ten minutes late helping them.

We discovered a number of injured people huddled in a room directly adjacent to the building containing the Hutus. As we moved in to retrieve the casualties, a Hutu pointed his weapon at us, but rapidly changed his mind when ten Australian rifles were pointed straight back at him. We used this building as a starting point, evacuating all those in the room in Red Cross trucks. It was at this point that we struck a major obstacle. The criminal element within the camp had spread the word that those who accompanied the white people from the camp would be macheted to death on reaching their destination. This was widely believed and, as a result, only a few people could be persuaded to leave the camp that morning. On several occasions, women handed over their children to us, believing that ‘the white people will not kill children’.

The Australians found the attitude of these people incredibly frustrating. We could find no way to convince the majority of the displaced persons to leave Kibeho for the safety that we could provide. Many said that it was better to die where they were than to die in another camp. Even when we did succeed in persuading some to leave, a Hutu would often appear and warn those people that they would be macheted if they left with the Australians. This was a warning that never went unheeded.

At 2.00 p.m. that day, we were rotated out of the camp. We felt sick with resentment at leaving the job incomplete, but there was very little that we could have done for those people. We estimated that at least 4000 people had been killed over that weekend. While there was little that we could have done to stop the killings, I believe that, if Australians had not been there as witnesses to the massacre, the RPA would have killed every single person in the camp.

Permission to reprint this story as published in the Australian Army Journal is gratefully acknowledged.