Young Jack Simpson Kirkpatrick learned all about donkeys on the sands of South Shields at the beginning of the century. As a young lad during his summer holidays from Mortimer Road School he used to work as a donkey-lad for Mister George.

Donkey-rides on Herd Sands 1897. Mr George is on the right of the picture. (South Tyneside Libraries)

South Shields was at that time, and still is, a popular seaside resort in the north-east of England. Jack used to lead donkeys along Herd Sands beach, with little kids, or toddlers, or sometimes young ladies on board, for a penny a ride. He worked from 7.30 in the morning until 9 at night, when he helped Mister George take the donkeys back the three kilometres (riding one all the way) to the farm where they were stabled. For this Jack was paid the princely wage of sixpence a day. But if only Mister George had known, Jack would gladly have done it for nothing. He loved donkeys. In fact he loved all animals, but he loved donkeys in particular. Back home at 10 South Eldon Street, Jack kept rabbits in a hutch in the backyard, rabbits he sometimes used to swap with his friend Billy Lowes. Billy kept Flemish Giants.

Jack’s rabbits were of the black-and-white Belgian Giant variety. To his menagerie (which already included his dog Lilly) Jack would later add a ducket-full of pigeons - not to mention the four-legged, dappled-grey pony, and friend who would accompany him around the streets of Shields, for three years, on his milk round.

Tram stop number 8 in South Eldon Street, 1906. The Kirkpatrick family lived in this street from the time of their arrival in South Shields until they shifted to 14 Bertram Street, some time before Jack left home in 1909. (South Tyneside Libraries)

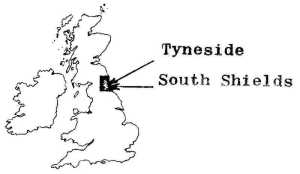

For the first eleven years of his life Jack Kirkpatrick enjoyed a normal childhood in South Shields, where he’d been born in 1892. Jack was a Geordie, that is, a person who is born on Tyneside, in the north-east of England, and who speaks with a strange, Scottish-like accent. Jack’s parents were both Scots; his father Robert, originally from Edinburgh, was the captain of a collier which sailed out of Tyneside carrying coals to the English cities of the south. He had formerly worked for the London and Edinburgh Shipping Line for twenty years as mate then master.

In 1886 he’d brought a freighter to Tyneside to be sold, and liking the area, and the people, he and his wife Sarah decided to settle here. They were very friendly people on Tyneside.

Jack had two older sisters, Sarah and Peggy, and his favourite younger sister, Annie. He had also had three elder brothers who had died in infancy, and an older sister, Martha, who died at the age of eleven, in 1900. Jack’s mother was naturally very protective of her only son, “Jacky-Maa-Lad”, as she called him, and whom she adored.

With Jack’s father a ship’s captain it is scarcely surprising that his greatest wish was to follow him to sea one day. Jack used to go down to Mill Dam in the mornings sometimes, where the sailors assembled outside the Shipping Offices for the signing on. Then he could mingle amongst them; rubbing shoulders with all these strangely dressed - Oriental seamen, with pigtails in their hair, or with sombre, severely-dressed, black-peak-capped sea captains, or with bearded, unkempt sailors of every nationality. They were all here, jostling and talking, in a multitude of accents, and dress - this wild, curious, exciting mix of seafaring humanity. Then he could imagine himself as one of them.

The South Shields Ferry at the beginning of the century. (South Tyneside Libraries)

The Tyne packed with shipping, 1895. (Newcastle upon Tyne City Libraries & Arts)

Jack loved all the sights and sounds and smells on the river - the tarry smell on the boats, and the salty tang of the spray coming off the water. But most of all Jack loved to be on the river, and he could do that - for a halfpenny. That’s all it cost, to go on the ferry from Shields across the river to North Shields. And he could stay on as long as he liked, all day if he wanted to. On board the Shields ferry and on his way across the river, yet again, hanging over the rails, Jack could look up river at all the river traffic on this, one of the busiest ship-building centres in the world at this time.

Jack could look back at the scummy wash lapping up against the pylons of the ferry landing. So what if they called it “the filthy Tyne”. That was ‘alreet’. He didn’t mind. All the way up on both banks of the river, as far as he could see - through the smoke haze, that is - was a solid mass of shipping, with ships lying at anchor out in the channel. In some places there hardly seemed room for ships moving up or downstream to get past each other. He loved listening to all the noises on the river, the “music” on the river.

Every boat and ship had its own siren - its own voice, he liked to think, setting them all apart, making them all different. He loved watching and listening to the tugs, these fussy little old ladies of the river, bustling about, full of their own self-importance, sounding off officiously with their shrill little whistles and toots to the rest of the river population, demanding clear way. Then a freighter might make its lumbering way upstream, its slow, steady passage preceded well ahead of it by a series of long, loud blasts. Or a liner might go sailing graciously by, in amongst all these filthy colliers and tramp steamers. Or a sleek grey warship, a destroyer no less might appear from nowhere, gliding menacingly by. Everywhere he looked there was a feast of ships - trawlers, tugs, freighters, liners, warships, and sailing ships. They were his favourites. And he could identify every one of them, thanks to his Dad, all the barques and brigantines and schooners and yawls that came into the Tyne.

From both banks all the way up and down the river, from the shipyards and engineering works came yet another kind of “music” the never-ending racket of banging and clanging, which rises to an awful ear-splitting intensity as Jack approaches the far bank, with the sudden machine-gun hammering of a riveter nearby, followed by the screaming whine of tearing metal (accompanied by a shower of sparks) which goes echoing across the water. And Jack loved it. He loved all this noise, the excitement, the activity. One day he was going to be apart of all of this. One day.

In 1904, at the age of twelve, Jack had to suddenly stop being a child and become the man of the house. His father was brought home after a crippling accident on his boat. He would never work again. Indeed, he only had another five years left to live.

Before the accident it had always been expected that Jack would become an engineer with one of the local engineering works, like Hawthorne Leslie or Tyne Dock Engineering. Now all that was changed. There were no unemployment benefits, workers’ compensation or old age pensions in 1904. Jack left school to become the breadwinner of the family. His mother took in washing. Between them the Kirkpatrick family managed to survive. Jack went to work for Fred Patterson, the local milk merchant in South Frederick Street. Jack had to leave home when it was still dark to get to the dairy by 5 am. In those days the farms sent their milk to the towns and cities in seventeen-gallon churns. Someone from the dairy had to be at the station to meet the train with a horse and cart and bring the milk back to the dairy. So everything had to be made ready so that the milk floats and bogies could go straight out. The horses had to be fed and harnessed for one thing. So from the moment Jack arrived he would be hard at it.

For his first two years as a milk lad Jack pushed a milk bogie around the streets and backlanes of the Tyne Dock area, where he lived, ringing his bell and calling out in a sing-song voice - Milko. Women would come to their doors with jugs which Jack would fill from a hand churn which he kept topping up from the big churn on his bogie. Then he’d take payment. He usually finished his round by about midday, then went back to the dairy where his work was far from over. All the hand churns and the big seventeen-galloners had to be cleaned. As had the dairy itself, not to mention all the unharnessing and feeding and grooming of the horses -which Jack didn’t mind in the least. In fact it was often Jack who went back to the dairy at night, to give the horses their evening feed.

At the age of thirteen Jack’s love of the sea was as strong as ever. But he knew there was little chance of that dream being realised, things being the way they were. Every chance he got, however, he was on or near the river. Jack had a friend, John Shaw, a few years older than himself, who worked for a shipping butcher, Andrew Anderson, to whom Jack delivered milk, which was taken out to the ships in a sculler boat. Jack was forever pestering his friend to let him go along on these deliveries, and on one occasion they were out on the river when the wind blew up quite fierce. They were nearing the ship to make their delivery when Jack fell overboard. With all the movement on the water it took some doing for Shaw to haul him back on board, and in the process Jack fell in again. Eventually the older boy managed to get him back safe and sound into the boat. But Jack’s immediate thoughts weren’t for his safety. “Look at me tabs!” Jack complained, looking at a penny packet of Woodbines he’d pulled out of his pocket. The cigarettes were soaked through and useless. “Never mind your tabs, man”, Shaw replied. “It’s your life you should be thinking about.” John Shaw recalled this incident often in later years, and the kind of character his young friend was.

Jack had another memorable encounter with the murky waters of the Tyne at around this time, when he dived into the river near the Tyne Dock Gut, and pulled out two drowning children.

When Jack was about fourteen he was given charge of a milk float, together with the dappled-grey pony that pulled it, and who would be his companion and friend over the next three years. Jack’s milk round was still in the same general area, around “the Deans”, but it was now extended, and it was along the backlanes of Dean Terrace, Alexandra, Francis and Florence Streets Jack now wandered, ringing his bell, as well as along Conway Terrace, John Williamson Street, Temple Street and Dean Road. But Andrew knew the route blindfolded, where to stop, and when to move off again. Jack virtually just had to walk alongside, measuring out the milk and taking payment.

Jack’s four-legged companion around the streets of Shields, Andrew. (Courtesy of John Simpson Parkin)

Jack liked the outdoor work. The bitter cold and darkness of early morning might have taken some getting used to at first, and he had to cop a drenching now and again. But that was OK. He could take that. He liked to think that, like most Geordies, he was pretty tough. In winter it was especially rough - exposed to the howling, freezing wind and the driving rain, with little or no protection. He couldn’t wear gloves. Apart from contaminating the milk they would have become saturated in no time, with him constantly dipping his measure down into the milk. So he just had to put up with almost perpetually frozen hands. And if it was bad for him it was just as bad for Andrew. Just making headway on the icy streets at times, was a hazard. At times there was nothing for it but to hammer metal studs into Andrew’s shoes to let him get a grip on the icy surface. Then the studs would be taken out again in the afternoon, after the round was finished.

In the second week of October, 1909 Jack’s father died. Two days after the funeral Jack left home. He’d signed on as a storeman/steward with the SS Heighington, bound for the Mediterranean and North Africa. It almost broke his mother Sarah’s heart to have her beloved son leave home and go off hundreds, even thousands of miles away. But they both knew that this was the only solution. It had always been Jack’s dream to go to sea. He’d get a steady wage, from which he’d be able to send a regular allotment back home for the family. And they’d be able to take in a lodger now. The Kirkpatrick family would manage.