Numerals appearing in parentheses, eg (1), in or at the end of paragraphs indicate a cross-reference which appears at the end of the article.

Young WAAAF plotter, Connie Lawrie looked closely at the small model plane she had just pushed with a billiard cue type stick onto the bearing and range which had come over her headphones. She murmured ‘I don’t reckon it’s one of ours’ as her eyes flitted across to the ever watchful gaze of the duty recorder, her mate Rhoda Mathieson.(1)

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

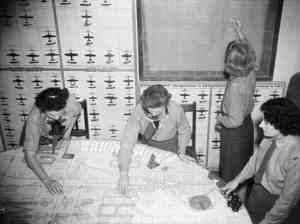

AWM 061303 Plotters at work.

Their eyes locked and, as one looking in a mirror, widened in unison as realisation dawned that Townsville was about to come under attack again. Rhoda briefed her sergeant who leapt up onto the stage and reported to the duty officer.

0001 hours 29 July 1942: Red Air Raid Warning. Townsville was in the front line of the steamrolling Japanese advance.

This was RAAF No 3 Fighter Sector Headquarters which had been formed at the Townsville Grammar School in Paxton Street, North Ward on 25 February 1942. As a result of the Government’s complete ban on the opening of coastal schools in January 1942, students had initially been dispersed to Charters Towers and the School had been rented to the Army Hirings Department.(2) Sister schools St Patrick’s on The Strand and St Anne’s in the city were also taken over by the RAAF.

Fresh from recruit training, 18-year-old Connie Lawrie and Rhoda Mathieson had arrived in Townsville by train in early April as part of the rapid Allied build-up. This began with an advance party from the United States Army Air Force (USAAF)

which flew into town on 5 January 1942. US Base Section 2, as it became known, was the North Queensland component of the United States Army Services of Supply Organisation. The Australian Mercantile Land & Finance Building at 32 Denham Street became its headquarters and was tasked with the dual responsibilities of constructing airfields and establishing the base.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM NEA0076 Members of the RAAF and WAAAF at a church parade at St Anne’s Barracks. St Anne’s, a Townsville girls’ school, was used as a barracks for service women during WW2.

The WAAAFs of Sector HQ were billeted in the St Anne’s Girls School on the corner of Walker and Stokes Streets in the city. From there, with a small pack of sandwiches in their haversacks, they were spirited away, 14 at a time, in covered trucks for their eight-hour shifts. (They did not know the location or the former school nature of their destination.) On the stage at the end of the first floor assembly hall were the shift duty officers representing anti-aircraft guns and searchlights, radio direction finding and high frequency direction finding elements, and fighter support. These American, Navy, Army and Air Force officers were in constant radio and telephone contact with the eyes and ears of early warning, air raid alert and fighter response units.

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 150101 Townsville, July 1942. Hidden under its effective camouflage, this sound detector was ready to pick up the sound of enemy aircraft. It was an essential part of a coast artillery anti-aircraft battery and was manned by US Army personnel.

Unknown to the young volunteer WAAAFs, General MacArthur had formally assumed command of Australian forces and established General Headquarters South West Pacific Area in Melbourne on 18 April. From that organisation emanated a chilling assessment on ANZAC Day 1942:

Possibility of AIR Raid by carrier based aircraft in force against EAST coast of Australia, by 2 May. Combined with landing attempt at PORT MORESBY also possibility of feint against DARWIN. You will take every precaution for protection of personnel and supplies, and will ensure anti-aircraft weapons on all ships in your port are manned, repeat, manned, twenty four hours a day.(3)

The WAAAF plotters proliferated the body of the assembly hall of the Grammar School and it was here that the young women in uniform had been carefully plotting and recording information on all approaching aircraft day and night since February. Apart from three cheeky Japanese high altitude reconnaissance flights which had arrived unannounced over the city on 22 and 23 March and 11 May (4) - and disappeared with equal speed - there had been little excitement till three nights ago.

On that night of 25-26 July, Dr Rod Cardell who was only ten years old at that time recalls,

Townsville was caught unawares as two giant four-engined flying-boats leisurely flew around for half an hour while late-nighters enjoyed themselves in the brightly lit streets below. A couple of suspicious searchlights probed the moonlight sky and caught the raiders in their beams. An American light anti-aircraft battery opened fire to no avail. A stick of bombs dropped harmlessly into the bay before they returned to their base... (5)

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 068947 A Kawanishi four engine bomber reconnaissance flying boat - an "Emily" - used by the Japanese for bombing raids on Townsville in 1942.

Such was the unpreparedness of the military in the area that, when Red Air Raid Warning was finally signalled, the following exchanges were common. ‘Get your helmet on, Des. Didn’t you hear the raid alarm?’ admonished the sergeant in 101 Anti Tank Regiment. ‘Cripes, I thought it was the tea gong,’ replied the Gunner.(6)

Again, two nights later, Cardell was sitting ‘in a creek bed and watched with fear and excitement as another four-engined intruder was brightly illuminated in the searchlight beams and . . . antiaircraft shells exploded spectacularly in the sky without troubling them.’ Unfortunately a lack of coordination between Australian 3.7 inch ack-ack batteries and the fighters meant that the American Airacobras were unable to intercept the enemy because of the danger from bursting air defence rounds. From 15 000 feet the lone Emily flying boat dropped a stick of eight bombs near the foothills of Many Peaks Ridge mistakenly believing that this was the main Garbutt airfield (which was actually some 1.5 kilometres away).

The earnest report to the senior duty officer on the night of 28-29 July initiated an immediate scramble of activity, ‘somewhat like chooks with their heads cut off’ recalled Connie Noble with a smile. The order to launch the Red Air Raid Warning flare was still being passed when the arguments began. ‘The ships’ guns will fix them,’ said the Navy representative. ‘Only if our anti-aircraft sites leave you anything,’ asserted the Army officer. ‘Look, let’s be realistic,’ drawled the Yank, ‘our fighters will take care of these bogies before your blokes even see them.’

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM AC0024 A Bell Airacobra P-39 fighter aircraft in flight.

Strange as it may seem, apart from the disaster at Pearl Harbour and the surprise invasion of Malaysia, the young WAAAFs knew nothing of the following events: the fall of Singapore and the capture of the 8th Australian Division, naval losses in the Java Sea, the Japanese advance across the Kokoda Track, and bombings of Darwin and then Horn Island, all of which would have been ominous warnings of impending danger. News broadcasts and newspapers were heavily censored. Also unknown, the Battle of the Coral Sea (4-8 May) had denuded the Japanese fleet of two aircraft carriers and prevented the invasion of Port Moresby. Without air support from these two vital aircraft carriers for the Battle of Midway (3-5 June), the enemy experienced a defeat which was seen as a turning point in any perceived plans for the invasion or isolation of Australia.

There was not much levity in the lives of young WAAAFs in Townsville during mid 1942. Immediately on return to St Anne’s from their shift, they were fed and ordered to bed to recharge their batteries lest called upon sooner than expected. On awakening there were barracks cleaning, physical training and inspections. In the meagre periods of free time they would wander down to the YMCA or Salvation Army buildings where they played table tennis, read and talked with their fellow service mates.

Troops poured into Townsville daily. Hitherto unheard of military units opened for business. On 15 June the US 360th Quartermaster Bakery Section started operations and, with an output of some 5000 loaves daily, supplied all bread to the US Army. Just west of the city, the Remount Depot at Rocky Springs obtained and trained horses for pack work in New Guinea, where vehicle transport in many cases was impossible because of mountainous or swampy terrain.

Everywhere there were long queues of patient civilians with ration cards, Australian servicemen

with a few bob to spare, and Americans with money burning holes in their pockets. There were food and petrol shortages, no tyres or tubes, no travel permits, restricted and censored telephone calls and, worst of all, the city’s ice, vital for cooling ice chests in the long hot summer, was regularly commandeered to cool American bath water instead.

The mood of the city began to turn bitter. Troops roamed the streets in their hundreds. ‘It was an extremely difficult time,’ said former Townsville Grammar School teacher Gertrude Pohlmeyer. ‘We were on rations and they the Americans had good and plenty. They changed attitudes and they changed the pace of our lives,’ she said. ‘They taught us about greed and they taught us about refrigerators.’(7)

The night of the third bombing, 28-29 July ‘was spectacular to all on the ground’ Rod Cardell remembered,

Most people would have shivered in the cold night air as air-raid shelters were scorned and people positioned themselves for another gala performance. The antiaircraft guns were ordered silent and two American . . . [fighters] . . stalked from the darkness as the lone Japanese flying-boat was illuminated like a silver cross in the sky. Tracers could be seen passing like slow motion between the duelling aircraft.

Ten searchlights coned the flying boat as a pair of Airacobras swept in for six consecutive passes, raking their target with .3 and .5 calibre machine gun fire. US Captain John D. Mainwaring in the lead aircraft reported, ‘Our first burst silenced the rear gunner, and one of our shells seemed to explode inside the ship. Afterwards only the top turret kept on firing.’ During the attack, the enemy bombardier jettisoned seven bombs into Cleveland Bay between the mainland and Magnetic Island. They all landed well clear of shipping which had earlier been dispersed from the wharves into the area. The Emily then dived to escape being illuminated and the fighters’ attacks.(8)

An eighth bomb exploded close to the racecourse shattering a few nearby windows. It created a large crater and damaged a lone palm tree. The fighters sought desperately to relocate the diving Emily until a lack of fuel forced their return to Townsville drome.

It was therefore with some trepidation that the people of Base Section 2 faced the dawn of 29 July 1942. Was the Japanese ebb tide of Midway turning again to a flow against Townsville?

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM 150165 Japanese air raids on Townsville caused little damage and few casualties. However, the danger of unexploded bombs was ever present, particularly to Allied shipping using the harbour. A bomb disposal squad searches the shallows for evidence of bombs.

Nightlife in Townsville continued on a most sombre note for the next month till the news of the first defeat of the Japanese on land by the Australian force at Milne Bay (26 August to 7 September) permeated through by letters from relations in arms. This was closely followed by the Australians halting the enemy’s Kokoda advance at Ioribaiwa Ridge (17 September). Now the tide had really turned and the Japanese snowballing march was melting.

Both Australian and American divisions streamed through Townsville en route to chasing the Jap back to his homeland. The new transient population saw Townsville as the first and last chance to get rip-roaring drunk. Prostitution was rife. The incidence of venereal disease soared. Gertrude Pohlmeyer remembers that condom outlets were always lit by blue lights so that they could be found during blackouts. GIs soon dubbed Townsville ‘the hottest, dirtiest, lousiest, toughest and most overcrowded troop town this side of Louisiana’.(9)

Like to copy this image? Please click here first

AWM P01443.002 The operations building for No 1 Wireless Unit, RAAF at Stuart Creek, ten miles west of Townsville. This was an ultra secret intelligence unit attached to the Central Bureau of Intelligence where they intercepted and decoded Japanese military signals. The building was camouflaged as a house but only the tanks and steps were real - all other features such as windows, railings and the trellis were painted onto the walls of reinforced concrete.

Nevertheless, the Americans created a fascination for young WAAAFs. Connie Noble’s eyes still sparkle recounting the atmosphere of the dances at the Garbutt Air Base ‘like Hollywood with all the music’. There was, indeed, a side to the GIs that enraptured young Australian girls but as Connie also recalls, this was aptly classified by Australian servicemen as ‘overpaid, oversexed, and over here!’

It seemed a lifetime since 19 January 1942 when the United States Liberty ShipPresident Polk arrived at Townsville’s No 5 wharf and began disgorging amphibious DUKW ‘Ducks’, jeeps and a plethora of equipment and supplies. Nearby theTophee discharged the first twenty two P39 Airacobra aircraft.

The first Australian Army reinforcements to arrive were from the 5th Division. Advance parties arrived at the end of April, closely followed by the main party with Brisbane’s 5th Field Regiment of artillery and the 29th and 11th Infantry Brigade Groups. Before Pearl Harbour, however, 2 Battery of 101 Anti Tank Regiment RAA arrived in Townsville by train at 0200 hours on 25 November 1941 as part of the divisional troops’ complement allocated to that city’s Militia 31st Infantry Battalion.(10)

The Allied Works Council (AWC) had been established in late February and in Queensland the Main Roads became the constructing authority. It impressed all types of mechanical equipment in North Queensland for the purposes of building roads, airstrips and defence works. Between 1942 and 1945 the corridor between the road and the railway line from Townsville to Charters Towers became one of the largest concentrations of airfields, repair facilities, stores and ammunition depots, fuel storage areas and port operations in the South West Pacific.

It was difficult to realise that Townsville, this sleepy, sprawling, overgrown country town of 35,000 people at the beginning of 1942 had experienced 5000 voluntary evacuees, won the fight to retain a further 10,000 which the Army sought to deport because of their desperate need for housing, and was to achieve a population of 120,000 (75 percent of which were service personnel) by mid 1943. (Interestingly, it took Townsville some 50 years to return to these numbers.)

The stoic citizens remaining in US Base Section 2 endured wartime deprivations including constant road and air blockades; ‘brownouts’ which masked out vehicle headlights then total blackout conditions; severe shortages and rationing of food items; a scarcity of water, petrol, clothes and ice which was so critical to their primitive refrigeration systems; and were forced to comply with movement restrictions in or out of the garrison city.

Sixty years ago, Townsville 1942 had indeed been in the front line.

Endnotes:

Author and Connie Noble (nee Lawrie) on 24/10/01.

Allen, Kim History of The Townsville Grammar School 1888-1988, Boolarong Publications, 1990, p 144.

AWM 52:1/8/24 cited by Nielsen, Peter Diary of WWII North Queensland, Nielsen Publishing, Smithfield, NQ, 1993, p 30.

‘Japanese Naval Flights Over Queensland During World War II’, Military History Department, National Institute of Defence Studies, Tokyo, as cited in Mentioned in Despatches, newsletter of the Victoria Barracks Historical Society, Brisbane Incorporated, Vol 11, Iss 6, June 1998.

Cardell, Rod ‘The American Fifth Air Force Service Base and the Stockroute Airstrip’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol XV, m 2, Albion Press (Qld), Brisbane, May 1993, p 82.

The Reunion Committee The Story of 101 Australian Tank Attack Regiment (AIF), Brisbane, 1976, p 37.

Brown, Heather ‘Australia 1942 - The Most Dangerous Year’, in The Australianmagazine, ed James Hall, Nationwide News Pty Ltd, Canberra, 25-26 January 1992, p 10.

Piper, Robert Kendall ‘Townsville Under Attack’, a photocopied undated but obviously published article in the files of the 101st Tank Attack Regiment Association held by Arthur Burke, the son of Captain (Retired) J.F. Burke of Brisbane. The author claims ‘Copies of the original Japanese, American and RAAF/RAN intelligence reports have recently been obtained by the author and now enable the true story, from all sides, to be told for the first time.’

op cit Brown, p 10.

From the wartime diary of (then) Lieutenant J.F. Burke held by his son, the author of this article.