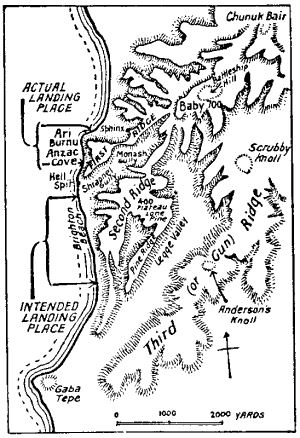

The ANZACs came ashore approximately two kilometres north of their planned landing area due to a navigational error on the part of the Royal Navy. The terrain they were confronted with is the most wild and savage in the entire Gallipoli Peninsula. When the general staff were reconnoitring the Gallipoli coastline from the decks of the battleship Queen, on April 13th for possible landing zones, one area ruled out without question was this spot where the Anzacs were now coming ashore, terrain which would have deterred adventurers in peacetime.

The Landing at ANZAC. April 25th, 1915. (by courtesy of ‘The Courier-Mail’.)

ANZAC, the Landing. 1915. By George Lambert, 1920-1922. Oil on canvas, 190.5 x 350.5cm. (Australian War Memorial (ART02873). The charge up to Plugge’s Plateau. The Sphinx can be seen in the background.

The men from the battleship tows landed first, around 4.30 am, in and around a cove dominated by a 100-metre rugged hill, which they immediately set about climbing, under intense machine-gun and rifle fire from the Turks on the plateau above. The tows from the destroyers Ribble and Usk landed their soldiers slightly to the north of the cove. On board the Ribble Capt. Douglas McWhae was waiting for the return of the lifeboats, being towed back by a steam pinnace. It was almost light now, about 5 am and a savage machine-gun and rifle fire was being directed at the ships and the men coming ashore by Turks on the cliffs above the beach. Bullets were clanging off the destroyer’s armour plating. McWhae recalled:

“Several men were wounded on the destroyer and a young naval officer shot dead through the head (while waving the men off with a ‘Good Luck’) and Symonds of B Section shot through the chest. I saw one infantryman shot, fall into the water and drown with heavy pack despite the efforts of one of the sailors to save him. The rowboats returned to the destroyer and we entered them under heavy fire. Then we rowed to shore under a frightful fire.”

McWhae’s C Section was packed into one boat so tight that Jack and his mates could hardly move. Lyle Buchanan’s A Section was in another boat. The last 50 metres or so row to the beach, after the pinnace had cast off, was a terrifying experience, under heavy fire all the way in. Buchanan remembered it vividly:

“I don’t know what it was, shrapnel, maxim or rifle fire - I was frightened to look, but I was never so frightened in my life as when I had to stand up in the bow to dominate the men (to keep rowing)... I could feel the damned things hitting me all the time in my imagination, while we couldn’t see the other boats for the spouts of spray all around, and the men hit yelped and then whined and clawed the air as they died.”

“At first the beach was absolutely swept with machine-gun and rifle fire”, McWhae recorded, “so that there was no possibility of going near the boats (of the first tows) or to help the wounded lying on the beach.” Jack’s boat grounded in deep water, about 300 metres north of Ari Burnu Point, almost opposite the Sphinx. He was the second man out of his boat. The first and third men out, on either side of him, were killed instantly. During the landing the 3rd Field Ambulance lost three bearers killed and another fourteen wounded. One of those wounded was Otto Kirkby. His diary records the events after the lifeboats returned to the destroyer: “We took a wounded and a dead chap out of the boat before we could get into it. Meanwhile the Turks were firing at us. One of our chaps was hit through the shoulder otherwise we got away from the destroyer alright. Then came the awful time. We were pulled some of the way by a pinnace but had to row a long way. The poor sailor that was rowing just in front of me was shot through the head a couple were wounded too. We got within 10 yards of the beach when we began to scramble out of the boat. I fell over the starboard side and made a rush through the water. I fell a couple of times and regained my feet again. I scrambled ashore and got about 3 yards ashore when I felt an awful smack on my side & I knew that I was shot. I crawled for about 5 yards and found I could not go any further. So as the bullets were whistling all around us I put a few stones around my head and laid there for about 15 minutes. The boys had chased (the Turks) back again by this time so I crawled to my mates and they fixed me up. The doctor took the bullet out of my wound. I laid there till about midday.” Kenneth Fry, Bearer Officer of B Section recalled his experience in a typical brief understatement “Struggled to land with storm of shots, shrapnel and the like about. Tumbled men into deep water and followed.” The bearers raced across the narrow stretch of sand and took what cover there was behind a low bank fringing the beach. “Sat tight for 20 minutes or so... Rowe hit, could do little, morphia given,” Fry writes. By about 5.30 a.m. the Turks had been driven off the cliffs above by superior numbers of Aussie soldiers arriving. “Soon after dawn the rifle fire stopped”, writes McWhae, and “we were able to look after the wounded - now shrapnel fire only. There were great numbers of wounded whom it took all the morning to attend to and get away”.

Capt. (later Colonel) Douglas Murray McWhae CMG, CBE. (Courtesy of Mrs Mari Millard).

Capt. (later Colonel) August Lyle Buchanan MID (Courtesy of Mrs Gail Penrose and the Buchanan family).

Pte. (later Sgt.) Otto Athol Kirkby MM (Courtesy of Jim Kirkby).

A primitive collecting post was established using the cover of the overgrown vegetation beyond the beach. “The Red-Cross flag was put up after a time”, McWhae continues. “The three sections were going for all they were worth... they had iodine and field dressings; all splints were improvised using rifles and bushes. They were terrible wounds to deal with.”

Sometime around 6 a.m. a Major Jackson, of the 7th Battalion, arrived at the collecting post requesting urgent assistance for his men about 1200 metres north of the Sphinx and at the extreme left of the landing area.

Fisherman’s Hut, in front of which a gruesome scene confronted the bearers of C Section, 3rd Field Ambulance on the morning of April 25th. (Photo by author, 1993).

Looking down from Russell’s Top, near The Nek, to Fisherman’s Hut. It was up the high ground between this razor-back ridge, and The Nek, the bearers of 3rd Field Ambulance climbed on the first day, to clear Baby 700. (Photo by author, 1993).

McWhae and C Section set off at once, skirting the chest-high thorny bushes inland which they used for cover. When they arrived at their destination - a small hillock with a fisherman’s hut at its base, it was a gruesome scene which met their eyes.

At the water’s edge, three boats were grounded. In front of these lay a line of men, unmoving. The boats themselves retained a part of their grisly cargo, held frozen in a variety of postures - some lying, some still sitting bolt upright, pressed tight together, dead where they sat.

In one boat “a sailor was lying in a life-like attitude, chin on hand, gazing up at Walker’s Ridge.” In another “a dead man sat with an arm thrown over the gunwhale.” Of the original 140 occupants only 35 were unscathed. The rest were either dead, dying or seriously wounded. The boats had been caught under direct machine-gun fire all the way in. With the Turks having been driven off the cliffs above the ambulancemen carried the wounded up the beach to shelter and began treating their wounds. Later in the morning Buchanan brought A Section up the beach and a collecting post was established somewhere near Fisherman’s Hut. Fry remained near the Sphinx with B Section. After treating all the wounded on the beach the ambulancemen began climbing the razor-back ridges to reach the wounded on the cliffs above. B Section climbed Walker’s Ridge to clear the seaward ridge, later to be named Russell’s Top, while A and C Sections began the scrambling climb up the razor-back approach to clear the wounded on Baby 700. Just managing it across these 150-metre-high spiny ridges, along a heart-stopping goat track which allowed for single traffic only, unencumbered by a stretcher, would have been a feat in itself. How the bearers made that trip repeatedly, bringing the wounded down from the heights defies the imagination.

Between 9 and 10 am the Turks began a massive counter-attack. By midday they were in possession of all the high ground around Baby 700 and the collecting post at Fisherman’s Hut (where there “were over a hundred wounded” according to McWhae), was under serious threat. By 2 pm the Turks were holding the foothills and spurs leading down to the beach. It was a desperate scramble to evacuate the wounded ahead of the Turkish advance. Private Cedric Rosser, of C Section, won the first Distinguished Conduct Medal awarded at Anzac for his role during this evacuation. His citation records that: “Totally regardless of the danger... he showed the greatest bravery and resource in attending to the wounded... under a continuous and heavy shell and rifle fire dressing and collecting the wounded from the most exposed positions.” Under Rosser’s supervision most of the wounded were loaded into the boats grounded near the shoreline. While this was going on bearers continued carrying casualties from the Firing Line right up until the last. “3 Field Ambulance bearers showed great bravery in evacuating from the Front Line over open ground as the retirement continued”, Lyle Buchanan wrote, “the obvious nature of their work seemed to offer no safeguard at all ... stretcher bearers worked their way through and in several instances were between the Turks and our own parties.” The boats were rowed off, just in the nick of time, with Rosser in control. “He was not long away”, McWhae noted. The boats were taken in tow by naval pinnaces and taken out to the hospital and transport ships. The remaining bearers made their way along North Beach, and past the Sphinx carrying the wounded. They made their way around Ari Burnu Point and in to Anzac Cove, where they were urgently needed to help dress the wounds of the mounting casualties. Otto Kirkby remembered being carried along the beach by “Andy (Davidson) and Ted (Langoulant). We laid on the beach till about 5 o’clock. Shrapnel was bursting over our heads all the time. We got off at last in a horse barge.” By evening the entire twenty-five metre width of the southern end of the beach was covered to a distance of about a hundred metres with wounded, the bodies lying so close together, on stretchers or groundsheets, that it was difficult to pick a way through them.

Pte. (later Cpl.) Cedric Hereward Rosser DCM (Courtesy of Father Brian Rosser).

The British military leaders had confidently expected that the Turks would put up a token resistance against the invasion force then turn tail and run in the face of a “superior” British Army. But the Turks fought fiercely in defence of their homeland. There were over 2,000 Australian and New Zealand casualties at ANZAC on this first day (with 3,000 British and French casualties further south at Cape Helles). The British leaders had predicted that no more than 5,000 casualties would be sustained by the entire 75,000-strong allied army in the winning of this brief campaign. The actual figure would be 252,000 casualties, with 51,000 allied soldiers killed over an eight-month campaign which they would lose.

By 2 am on the morning of the 26th the last of the wounded had been cleared from ANZAC Cove and taken out to the hospital and transport ships. ‘Slept on the beach’, Fry records. ‘By this time we had no stretchers and had to wait for returns from the transports.’ Unfortunately, to a large extent these were not forthcoming - presenting a major and unforeseen obstacle over the next few days.