by Lyn Marsh

This article and images have been reproduced from the ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee publication, ANZAC Day 2004.

The drive from Istanbul to Gelibolu (Gallipoli) in the early morning light was not overly impressive -- miles of sprawling, half-finished apartment blocks and depressing housing estates. There is no attempt to vary the style, no gardens, parks or street planting. Where children run and play, I have no idea. Finally, it all opened up to fields of sunflowers and expanses of water -- the long-imagined Dardanelles.

I was so pleased at this point not to be here with the thousands who arrive for ANZAC Day. There is a poignancy about the place which needs to be quietly absorbed; the wind blowing through the pines; the silence broken only by the sound of birds; monuments to ANZACs and Turks at ANZAC Cove, Lone Pine, the Nek, Chunuk Bair and all the other sites where courageous men gave their lives.

Beach Cemetery, near ANZAC Cove. The peak on the skyline is the feature known to all original ANZACs as The Sphinx. Photograph courtesy Mary Long.

It was an enormous privilege to have as our guide Ali Efes, a historian, University lecturer, and retired Turkish naval officer, who grew up in a nearby village, and explored throughout his childhood the battlefields where his grandfather had given his life fighting the ANZACs.

He presented each of us with a little box containing a couple of worn worry beads, parts of his collection of relics from the dirt amongst the trenches. Rolling those between my fingers as I walked around, my heart went out to the men of both sides who had faced each other, at times not six metres apart.

ANZAC Cove, Gallipoli, with The Sphinx prominent on the skyline. Photograph courtesy Mary Long.

Ali’s detailed history lesson was fascinating, and even more impressive to hear it from a Turkish man who has made it his life’s work. I learned more in those six hours with him than I have ever absorbed from reading history books. I heard of the extraordinary respect the Turks held for the ANZACs, and understood why we, as Australians, had been welcomed so warmly since our arrival in this country. Together, we gazed out to the sea where so many Allied troops had perished; ordered overboard where, out of their depth and weighed down with 44kg packs, guns and heavy woollen uniforms, they perished before their feet ever touched Turkish soil. Turning, I looked up at the impossible cliffs of the Sphinx, disbelieving that anyone could have scaled those heights laden as they were, let alone under enemy fire.

Ali took us through trenches of both sides; where men threw messages across to each other; where the Australians tossed cigarette papers for the Turks to roll their own tobacco, and the Turks reciprocated, throwing tomatoes and fresh fruit to the ANZACs who were struggling on scant rations and limited water brought all the way from Egypt.

The tales abound of a spirit of camaraderie developing between the opposing forces; to the extent that eventually the men in the trenches deliberately aimed over the heads of their enemy, much to the frustration and ire of their superior officers. Romantic notions perhaps, but history books are full of ‘facts’, so what harm is there in believing a gentler story? Great respect was shown between ordinary men who found themselves the pawns of politicians, playing out the never-ending game of war.

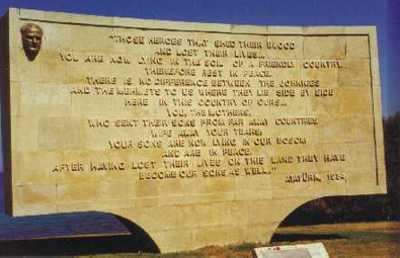

The monument, in one of the Turkish cemeteries at Gallipoli, to which Lyn refers in her story. Photograph courtesy Mary Long.

The tour of Gallipoli was not yet over. We stopped at a Turkish cemetery, where stood a tall bronze figure of an old Turkish veteran, his granddaughter at his side. It is a tradition of local women to pick flowers and sprigs of Rosemary from the garden at the base of the statue to place into the hands of the child. Ali asked if any of us would like to do the same as a mark of respect. I stepped forward immediately, recognising that the younger women present were hesitating. I tucked the sweet-smelling offering into the hands of the little girl, and as I stepped back, Ali took my own hands, and looking into my eyes proffered a small gift from him and his wife as thanks for my gesture.

I choked back tears as I opened my palm and saw a key ring made from a spent bullet from the battlefield. You see, I am a war widow. My late husband had fought in Vietnam, and when we first met he had given me a similar key ring, with a bullet from that war.

What incredible irony -- here, within another generation, we share gifts and embrace our grandfather’s enemy! Now I have been given similar relics of two wars, on different continents. That the bullets, which may well have ended lives two worlds apart, become as mundane as key rings, screams to me the futility of war.

Will we never learn?

The famous and evocative monument at ANZAC Cove inscribed:

Those heroes that shed their blood

and lost their lives…

You are now living in the soil of a friendly country.

Therefore rest in peace.

There is no difference between the Johnnies

and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side

here in this country of ours…

You, the mothers,

who sent their sons from faraway countries

wipe away your tears;

your sons are now lying in our bosom

and are in peace,

after having lost their lives on this land they have

become our sons as well.

Ataturk, 1934

Photograph courtesy Kevin Long.

The following was written by the Athenian statesman, Pericles (c. 495–429 BC), more than two thousand years ago; eons before the first ANZAC Day but only a stone’s throw from Gallipoli.

Each has won a glorious grave -- not that sepulchre of earth wherein they lie, but the living tomb of everlasting remembrance wherein their glory is enshrined. For the whole earth is the sepulchre of heroes. Monuments may rise and tablets be set up to them in their own land, but on far-off shores there is an abiding memorial that no pen or chisel has traced; it is graven not on stone or brass, but on the living hearts of humanity. Take these men for your example. Like them, remember that prosperity can be only for the free, that freedom is the sure possession of those alone who have the courage to defend it.