by Beverly Wright

Rwanda: how quickly this country became the focus of world media attention. Genocide, on a scale unheard of since World War 2, was presented to a massed television audience nightly in living rooms around the world. Estimates of the civilian death toll ranged from 500,000 to 1,000,000 during the carnage of this civil war.

Like so many Australians, I was distressed by what I saw. Little did I know that I would soon be on my way to Rwanda, along with a contingent of over 300, as part of the Australian Medical Support Force UNAMIR II (United Nations Assistance Mission For Rwanda). The force’s task was to establish a hospital facility to provide health care to the 5,500 United Nations troops who were part of UNAMIR II. To those in the military, overseas deployment is seen as the pinnacle of service life. It was truly the ‘chance of a lifetime’ to those of us with the opportunity to go to Rwanda.

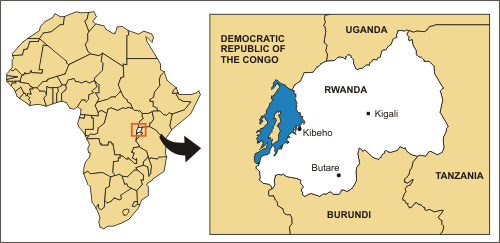

Rwanda in context. The main places where Australians were employed are marked.

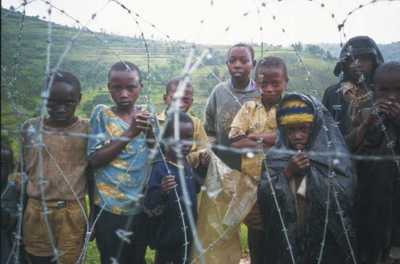

AWM P02211.014. Murambi, Rwanda. Children belonging to the Hutu tribe standing outside a barbed wire enclosed Displaced Persons (DP) compound. Some are wearing plastic bags as protection against the regular cold rain. They frequently congregated to beg food from the United Nations (UN) forces.

The majority of the contingent’s nursing officers arrived in Kigali around 22 August 1994. Kigali Airport was dark and eerily quiet. The heavens opened as we arrived, so by the time we were transferred from the American Galaxy transport aircraft to the terminal, not only were we anxious, apprehensive and tired, we were wet as well! For the first couple of hours, the war-damaged terminal was our temporary home. The lighting was subdued and there was obvious structural damage to the walls and ceilings from rocket-propelled grenades and mortars. Only one or two toilets worked (after a fashion) and the toilet paper was purple -- something that struck us as a little incongruous amid the destruction.

At 6.00 am, after a night spent sleeping with one eye open, we were ready to move to the barrack blocks. Our trip from the airport to our base for the next six months was particularly memorable for the gum trees we noticed en route, which reminded us all of home. It was incredibly hot, and the air around us was filled with the smell of death and the overwhelming stench of sewerage.

This was the first time since the Vietnam War that the Australian Government had deployed a medical mission of this size. Throughout our time in Rwanda we provided medical support to large numbers of people including United Nations troops; local Rwandans; ex-patriot Non-Government Organisation (NGO) personnel; UNAMIR employees; prominent Rwandans -- as defined by the Medical Director of the Central Hospital (Kigali) (CHK); and even the odd Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) soldier. This medical support was provided in a variety of different health care settings.

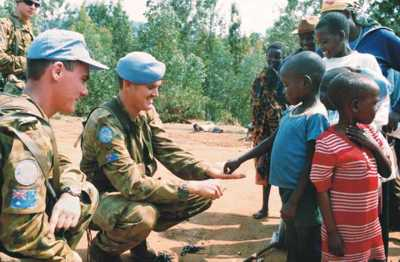

Photograph courtesy Public Affairs and Corporate Communications, Department of Defence.

The Role of the Medical Company

The Australian Medical Company comprised 93 individuals from 29 different medical units within the three services (Army, Navy and Air Force). Only the X-ray department deployed with a composite staff. This presented quite a challenge in terms of achieving the most effective combination of staff. The process would have been a great deal smoother had a formed unit, or at least elements of formed units, been sent.

The medical company was located in what had previously been the private obstetric wing of CHK. Members of an advance party, which had arrived two weeks prior to the main body, were faced with the difficult task of cleaning this wing. The area was covered with caked-on blood and faeces and party members had to manually remove waste from the toilet bowls. Evidence of significant carnage was everywhere: patients had bolted leaving intravenous lines dangling, and the walls were spattered with the blood of those fleeing for their lives. The smell, alone, was stifling. With the arrival of the main body, the cleaning continued unabated. With all members of the team on the ground, the newly styled ‘Military Wing’ of CHK was formed. It had the only intensive care unit in the country and, until the NGO element of CHK had its X-ray department in operation, the Australian Medical Support Force (ASMSF) contained the only X-ray department in Rwanda.

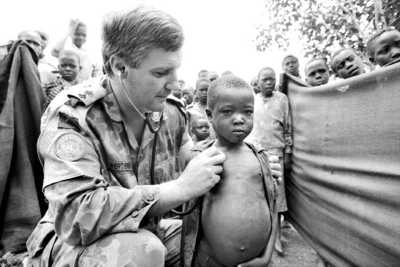

AWM MSU/94/0048/28. Kibeho, Rwanda. Lieutenant Colonel Michael Wertheimer, Commanding Officer of Tasmania’s 10th Field Ambulance based in Hobart, serving with the Australian Medical Support Force in Rwanda as the General Surgeon, examines a young local child at Rwanda’s largest displaced persons camp.

Within a few days of our arrival, we had our first patients in both the medical/surgical ward and the intensive care unit. The intensive care patient was a young RPA soldier who was given a below-knee amputation, following a grenade explosion. We basically ‘hit the ground running’. Staff members were exposed to a wide variety of trauma not seen in the peacetime military system back in Australia. The lead-up to this deployment had been very short for a number of our staff, and some were ill-prepared for the type of patients and the experiences they were to encounter. Many faced a very steep learning curve, yet, despite this, most performed exceptionally well.

AWM MSU/95/0005/25. Rwanda. A member of 4th Preventative Medical Company, Brisbane, who served in Rwanda with the Environmental Health Section. He is wearing protective clothing while using a fogging machine to control the mosquito and insect population near the accommodation area of the Australian barracks. Malaria is endemic to Rwanda and one of the jobs of the health section was to identify breeding areas and carry out eradication programmes.

AWM MSU/94/0001/28. Butare, Rwanda. 26 August 1994. Sergeant Joanne Cook smiles happily while washing her clothes outside in two plastic buckets.

AWM MSU/94/0014/31. Gitarama, Rwanda. September 1994. Local inhabitants line up outdoors, possibly to receive medical treatment from a couple of members of the Australian Medical Support Force.

Communication posed an immense problem. As the majority of Australians are mono-lingual, very few of us spoke Kinyarwandanise, French or Swahili. We resorted to local interpreters to provide the necessary link, almost all of whom had no experience in the area of medical terminology and, in particular, Western health care. In most instances, prior to the war, these interpreters had been university students or professionals with no medical knowledge. This made the act of gaining clinical details from patients incredibly time-consuming. We had to be creative with the limited resources available and could take nothing for granted. Improvisation always challenges creativity and we found ourselves richly blessed with ingenuity. As time passed, we began to see improvements in our conditions and, by the sixth week in-country, had treated a broad sweep of nationalities. An average week in hospital saw above- and below-knee amputations, grenade injuries, split skin grafts, delayed primary closure, debridement, injuries from motor vehicle accidents, gun-shot wounds, ventilated patients and a wide range of infectious diseases. Tuberculosis and malaria were prevalent, as were HIV and AIDS-related conditions.

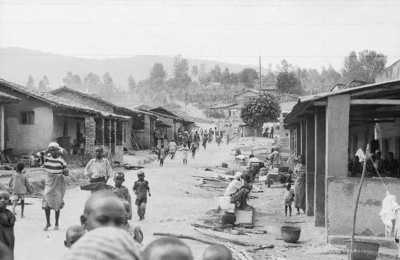

AWM MSU/94/0009/15. Busoro, Rwanda. 1994. Local children and inhabitants walking down the street and sitting on the side of the road in front of their brick and mud huts.

Treatment Section Group

Within one week of arriving in Rwanda, a Treatment Section Group was deployed to south-west Butare. Staff members were accommodated in the Medical School of the University of Butare, and here they provided a resuscitation capability with limited patient holding capacity. They would visit local clinics on a daily basis and, eventually, went as far as the Kibeho Refugee Camp, which was the largest in the country, holding 140,000 people. By November 1994, refugee numbers had fallen to 70,000, as Rwandans returned to their homes or fled back to Burundi. However, in April 1995, Kibeho Camp was once again the focus of world media attention when RPA soldiers massacred more than 4,000 refugees.

The refugee camps afforded many opportunities for nursing officers and, to a limited extent, medical assistants, to act as autonomous practitioners. Medical officers were not always available, and other medical staff members were treating up to 400 refugees per day. The most common conditions treated included worm infestations, malaria, flu, dehydration, malnutrition, meningitis and dysentery. Large numbers of those treated were children, and many refugees required dressings on previously untreated and infected war injuries.

Non-Government Organisations

The Australians quickly realised that the level of patient care provided by the NGOs at CHK required urgent attention to elevate it to an acceptable standard. Daily, as their capabilities and commitments permitted, ASMSF teams would assist in the NGO areas of the operating rooms, post-surgical wards and obstetrics. The humanitarian side of Operation Tamar was the secondary role for ASMSF personnel.

In November 1994, a contract was negotiated between ASMSF nurses, Samaritan’s Purse (Samaritan’s Purse is a Christian international relief and evangelism organisation which was founded in 1970. It is based in the United States and in 2004 was headed by Billy Graham’s son, Franklin Graham.) and Emergency (Emergency is a European-based non-government organisation that provides international emergency medical relief.) to render assistance in the NGO wards of CHK. The spirit of this contract was embodied in a philosophy of care which encompassed the sharing of knowledge with the Rwandan nurses, while improving the standard of care. We set out to achieve this regardless of the environment in which we worked.

The specific areas of need identified were many and varied. They were addressed by strategies such as initiating a daily ward routine which saw the Rwandan nurses included in ward rounds with ASMSF surgeons. This was vital in preventing patients we had cared for being neglected when they returned to the NGO section of the hospital. Mindful of the ever-present cultural differences, we aimed to improve hygiene, which was difficult, given the lack of running water and an ingrained reluctance to change old habits. We educated the local staff on patient lifting, post-operative care and insisted on daily revision in the use of oral and intravenous medications. Raising the patient care standard and working within the African culture was both frustrating and amusing, providing us with a constant challenge.

Aeromedical Evacuation

Aeromedical evacuation was not regularly available and was used only in daylight hours. Initially, we shared aeromedical evacuation responsibilities with the Canadians. A Spanish plane known as a CASA was located in Nairobi and helicopters were used for aeromedical evacuation in Rwanda. We also used the Mobile Intensive Care Rescue Facility, known by its acronym, MIRF.

The MIRF is an Australian design and is a self-contained transportation medical system with its own power supply, ventilator, monitoring equipment, infusion pump, suction unit and defibrillator. It can be fitted into planes and ambulances and it was found to be of greatest value in strategic aeromedical evacuation. Use of the MIRF meant that a critically ill patient could be left undisturbed until reaching the necessary health care facility for ongoing care.

AWM MSU/94/0015/26. Kigali, Rwanda. 1994. Private John Camiller (left) and Private Trent Bernard, members of 2nd/4th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (RAR), serving in Rwanda as part of the infantry protection element.

Conclusion

Throughout our time in Rwanda we saw the many highs and lows of health care in a Third World country. We were touched by the gentleness of people who had lost so much, and we became angry when we saw Rwandans continue to harm and kill their own people. We were amazed at the stoicism of both children and adults who had suffered significant injuries, and we endeavoured to understand a culture so different to our own.

While I feel privileged to have been given the opportunity to work in Rwanda, I only hope that we left some legacy for improvement within the Rwandan health care system. In essence, we were positive in our approach and persevered in assisting the local staff to become empowered to bring about effective change.

I do know personally that we did a great deal for so many who had lost so much, but I will always be haunted by a sense of hopelessness in what we left behind. The people of Rwanda still had such a long way to go in their search for self-sufficiency.