From the time Jack left his native shores it is possible to follow his career with a greater degree of clarity and exactitude, by virtue of his letters home, and later, by the testimony of others.

His first voyage seems to have been a useful learning experience for the budding sailor. Jack’s initial assessment of the Heighington as a “proper wreck... a rotten packet altogether”, with the crew’s quarters “flooded all the time and in the bunkers you are very nearly up to the knees in water” - during its stormy crossing of the Bay of Biscay - had changed considerably by the time he wrote his second letter home, two days later. As he told his folks then:

Now after we left the Tyne we did catch the weather until we got through the Bay of Biscay but she can roll for she has no balancers on her bottom. The first Sunday after we got out I had a good laugh they were having dinner when the ship she took a big lurch to one side then over come the soup, vegetables, meat and puddings all on top of the engineers knees and they could not stop them for they were hanging on to the table for all they were worth they did look dignified scraping all the rubbish off their pants and jackets and all the plates and dishes were smashed.

The two women who adored Simpson; left, his mother, Sarah; and right, his sister Annie, photographed in 1912, at the age of 17. (Courtesy of Annie’s son, John Simpson Parkin, of Essex, England.)

Two weeks later and life aboard ship - in the Mediterranean - was everything Jack had dreamed of: “Here I am having grand weather and little work and plenty of good grub and eating any Gods amount of it. I think I have eaten more in this fortnight than I have eaten in the last six months. I eat enough for two men at meals still I always feel ‘ungry’ I am getting an appetite like a horse.” Jack’s idyllic lifestyle was short-lived, however. He came back to the freezing climate of a British winter in December and was paid off in Leith, on the 16th. Jack spent Christmas at home with his family. On February 12th 1910 he set sail again, this time as a stoker on board the SS Yeddo, bound for South America and Australia. He was seventeen years and seven months old. The Yeddo turned out to be the genuine hell-hole which Jack - mistakenly and fleetingly, in his youthful inexperience, had originally taken the Heighington to be. Conditions aboard were so bad that when the Yeddo arrived at Newcastle, New South Wales, Jack and thirteen other crewmen jumped ship: a serious offence in the Merchant Marine. But Jack was now in Australia, a country for which he had always expressed a special affection. “My heart is in Australia”, he had often told Annie, “I’ll get there some way or other.”

Now he was here and over the next eight months Jack set out to discover what this Great Southern Land was all about.

Jack’s introduction to Australian life must have come as a revelation. In contrast with the dismal grey skies and the cold of northern England, the cane country of northern Queensland must have seemed like another world, with the vegetation, fruit and flowers growing everywhere in a profusion of colour that would have dazzled his senses; while up above the deepest of blue skies reached out, almost it seemed, for ever; and all around, amidst the lush vegetation and the drenching heat, the cloyingly sweet aroma of sugar, hanging drippingly in the air. This was sugar country after all.

But Jack wasn’t too impressed with a cane-cutter’s wages, or with the heat. He didn’t stay long. As he told his mother in a letter: “I got a start cutting cane on a plantation but it only lasted a week and I wasn’t sorry either for the heat was terrible it was 110 degrees in the shade and the money was small.”

Jack and a mate cut inland. They bought a “swag” between them -blankets, billy can and tent - and these two swagmen “beat our way through the bush for about 150 miles.” Jack’s mother was understandably concerned when she read this, believing her son had fallen on his luck. He reassured her in a later letter: “Now Mother... you will think that we would be like tramps in the old country but what a mistake the best of respectable men with a house of his own when he gets out of work he will just pack his swag and off he goes to where he hears work is on.”

Jack next tried his hand at being a jackaroo, riding the boundary fence on a cattle station. But this didn’t last long either. As he told Sarah and Annie:

I always fancied when I was in the old country that a job riding about on a horse all day would be all right but I had my bellyfull of riding in that one week you get into the saddle at daylight and you are galloping about till dark and change your horse twice a day. I soon found out that a cowboys life was no catch so we ‘padded the oof’ down the coast again we struck the coast at Cairns and I left my mate there and came down south.

Jack ended up working in the coal mines of Coledale then Corrimal, in New South Wales, from July until December. Throughout all this time he was sending money home regularly, in postal orders.

Corrimal was an attractive little mining town on the coastal strip between the Illawara Ranges and the sea. With its beach it no doubt reminded Jack of Shields - to a limited extent. As he wrote home: “I wish I was at Canny Old Shields... for this place is so quiet in fact I can feel my whiskers turning grey.” Life at Corrimal was enlivened for Jack, briefly, though probably not in a way he would have preferred. He was set upon by a drunken landlord, and he described the incident to his folks thus:

When the man and his wife were drunk they used to scrap like hell then he started with me and putting the tale all together he smote me across the head with a poker and put a cut in my head about an inch long after that I sailed in and then you could not see anything for dust for then I broke a chair over his head and in the struggle and scuffle and broke a good few things so he got a summons against me for assault and ‘breaking hup the appy ome’ but as both him and his wife was drunk and I wasn’t the case was dismissed.

Jack left Corrimal in December and worked his passage across to Western Australia where there was a gold strike on. But here again, “things were rotten... work was bad to get. There was men working for three and four bob a day... so I went back to the coast again. I got the chance of a second stewards job on the (Kooringa) so I took it for the time being.”

But Jack’s association with the Kooringa was to last longer than he’d imagined, from January 1911 until June 1913 in fact; and for most of this time as a stoker, gradually building up his physique for something which even now fate seems to have been preparing him for.

The SS Kooringa in which Jack sailed around the Australian coast. (Courtesy of John Simpson Parkin).

The Kooringa sailed around much of the Australian coastline, from Geraldton in Western Australia, across the Great Australian Bight to Adelaide, on to Melbourne, through Bass Strait and up the eastern seaboard as far as Newcastle, New South Wales. The work of a stoker, down in the bowels of the ship, feeding the furnace, with shovel after shovelful of coal, hour after hour, could never have been an enviable one. But Jack seems to have taken a pride in his work, and in his growing strength.

Every month, without fail, Jack sent a postal order to his mother for £3, out of his £8 wages. And in every letter home, almost without exception Jack made mention of the money he was either sending or had sent - and was checking to make sure his mother had received it. Sending money home in this way must have been a cumbersome and worrying business. But Jack had no choice. He could have made an allotment to his mother directly out of his wages, as he had done aboard the Heighington and the Yeddo - but that would have alerted the Marine authorities to the whereabouts of this deserter. He was still sending his letters home under the name of J. Kirkpatrick, however, and would continue to do so until he jumped ship a second time, in August 1914.

Jack spent Christmas Day 1911 at sea. Along with the rest of the crew he celebrated a kind of Christmas cum Boxing Day - in the true sense of the word. As he described it to Sarah and Annie:

We had goose and Plum Pudding and Brandy Sause and of course we drank each others health quite a number of times until each man thought he was Jack Johnson champion of the world then my mate suggested going over and having a fight with the sailors of course that was heralded as a noble idea and as the sailors feeling a bit lively themselves from sampling the bottle too much things went pretty lively for the next half hour you couldn’t see anything for blood and snots flying about until Mates and Engineers came along and threatened to log all hands forward.

We all had trophies of the fray someone bunged one of my eyes right up and by the look of my beak I think someone must have jumped on it in a mistake when I was on the floor but as they say alls well that ends well so I suppose it must be for both my eyes and my nose are all right now so that is the way I spent Xmas.

January 1913, and Jack was writing a yearly accounting to his mother:

“Now Mother I am sending you a PO for 3 quid so that this will be the last one for 1912. I have sent you 12 po for 3 quid with this one for 1912 making it 36 pound for last year so when you answer this letter you can let me know if you have received the 36 pound all right counting this with it. So with love to you and Annie.

I remain,

Your loving Son,

Jack."

In August 1912, from Geraldton, Jack had written to Sarah telling her he was thinking of leaving the Kooringa. He’d been promoted into the engine room as a greaser, “and the work is knocking me up I have been getting very thin and as pale as a ghost... it is a very light job I have got and a responsible job but I am thinking of turning it in as it does not suit me... I weigh above eleven and a half stone now. I cant eat I have lost my appetite for when I was firing in the stokehole I could eat like a horse for the Kooringa is a pretty heavy firing job and very hot so I think I will have a months rest then look for another firing job.”

But five months later Jack was still in the engine room. It was either the heat -" yesterday the heat in the engine room was 125 degrees so you will see that it is kinder hot" (he wrote on January 11th 1913) - or the fumes that was making him ill. In February 1913, from Port Kembla, Jack had told his mother, “I am making this my last trip on the Kooringa then I am going to have a spell.”

In March, again from Port Kembla, Jack told his mother that he’d seen a doctor who had told him he needed a rest. Jack’s main priority, however, was in making sure that “the exchecker held out.” He was “sick of going to sea”, by this time, “so that a spell ashore will do me good for I feel properly rotten and look more like a corpse than anything else of course it is the engine room that does it and I cant eat my grub like I used to.”

Finally, on June 11th Jack wrote to his mother from 616 Bourke St, West Melbourne, telling her: “I have left the Kooringa and I am having a spell ashore... Now mother I am sending you a PO for ten pound so that you will be all right for the next three months.” He added, “I will be 21 on the 6th of July.”

John Simpson Kirkpatrick on his 21st birthday. (Courtesy of John Simpson Parkin).

Jack had been laid up with influenza, “but I am beginning to feel all right again”, he reassured his mother, from 330 Raglan St, Port Melbourne. In fact Jack was ill for more than three months. But by December he was back at sea again, fighting fit, as a stoker on board the SS Tarcoola. “I am firing in this ship”, he told Sarah on the 31st, “but I am in pretty good trim just now I feel as fit as a fiddle. I weighed in last night and I went 12 stone 6 so that I am in pretty good nick for I have no soft fat on me.” As he said himself, “I think I thrive better on the hard work in the stokehole”

Jack’s spirit was reasserting itself along with his appetite. “Well Mother”, he wrote on March 1st 1914, “I had a row with the chief of the Tarcoola and I finished up I was out of work for three weeks before I joined this one”, the Yankalilla. The first stirrings of homesickness are also evident in this letter: “It is four years since I left home”, he writes, “I am beginning to get tired of this country. I think it would be just as well sailing out of home for the money is getting bigger at home and the money sharp goes here.”

By May 5th Jack’s homesickness had firmed into a definite decision to return to his Canny Old Shields. “I am going to try and hang this ship down for another eight or nine months and then I am coming home”, he wrote to his mother from Port Pirie, South Australia, “so see and start looking your best for next year for I am getting sick and tired of knocking about out here and you know the old saying that ‘Every bird likes its own nest best’ so you can look out for me next year even if I land home broke... P.S. I am enclosing a PO for 3 quid.”

In August 1914 the Yankalilla steamed into Fremantle where Jack was astonished to learn that Britain and Germany were at war. Here was a chance for him to do his duty, and get back home a lot quicker than he’d planned. He’d be sure to be sent to Aldershot to do his training before he was sent to France to fight the Germans - so there’d be plenty of time to get up to Shields to see his family in the meantime.

Jack jumped ship a second time, to join up. Fearing that a deserter from the Merchant Marine might not be accepted by the Australian Army Jack dropped his surname and enlisted as John Simpson.

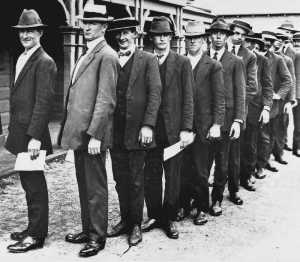

The coming war in Europe was greeted with enthusiasm and excitement in Australia. Men of all ages clamoured to join up, to be a part of “The Great Adventure”, as it was dubbed in the newspapers.

Volunteers enlisting at Melbourne Town Hall for a “Free Tour to Great Britain and Europe” and the “Chance of a Lifetime”, as promised by the recruiting brochures. (Australian War Memorial A03406).

Following his medical examination at Frances Street, Perth on August 23rd by Capt. Douglas McWhae, Jack was selected as a field ambulance stretcher-bearer. Only the strongest men in the army were chosen for this work, because of the intense physical demands placed upon them, carrying wounded soldiers for hours on end. The same day he was sent out to Blackboy Hill Camp, about twenty-five kilometres east of Perth, out in the bush, where he would meet up with the rest of C Bearer Section, 3rd Field Ambulance, and the men who would become his mates over the next nine months.