by Vanessa Seekee

Numerals appearing in parentheses, eg (1), in or at the end of paragraphs indicate a cross-reference which appears at the end of the article.

One of the least recognised groups of Australians to serve in the Australian Army is the men of the Torres Strait Islands. The Torres Strait is the 150 km of crystalline water that separates the southern coast of New Guinea from the tip of Cape York in Queensland. During the Second World War this shallow area of water dotted by coral cays and islands, proved to be a vital strategic point for the American and Australian forces pushing northwards through New Guinea. By the conclusion of the first 12 months of the Pacific War, 830 Torres Strait Island men, almost every man of eligible age in the area, would volunteer to serve their country. Thus was formed the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion, the only Indigenous Battalion ever to be formed in our nation’s military history.(1)

L-R (back): Gnr Kiwai Kusu, Gnr Nikira Mau, Gnr Garnia Kabai, and Gnr Arnuitu Yoelu (sitting). Photo: B. Araha, via the Torres Strait Heritage Museum.

The people of the Torres Strait are a proud and diverse people, with a background entrenched in the warrior ethos. This code was essential to the survival of each island’s community as often other groups would conduct raids, thus forcing the defence of their island homes. This background ensured that when another country waged war on theirs, they leapt to defend it, even though they were not considered in the Commonwealth census of the very country they strove to defend.

A group of soldiers from the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion on Horn Island, 1943. Photo: Longmore via the Torres Strait Heritage Museum.

During 1940, the Australian Government began to realise that should Japan be allied with Germany and enter the conflict, then a war would have to be fought on two fronts, Europe and the Pacific. This two-pronged approach would sorely stretch the human resources of Australia at the time. Thus the Director for Organisations and Recruitment suggested that the Torres Strait Islanders could be enlisted in the Australian Army, initially to allow the 49 Battalion to be released for service in New Guinea. Approval for the raising of a Company of Torres Strait Islanders was given in a letter from the Prime Minister, dated the 3rd May 1941.

"Investigations have indicated that the Torres Strait Islanders are well suited to be trained for military service and that there would be numerous volunteers forthcoming for such service at Thursday Island. As indicated in your letter of 14th January, the Director for Native Affairs would raise no objection to the recruitment of the Islanders."(2)

"Everyone got along famously." Gnr Don Myers, far left with Torres Strait Light Infantry soldiers, Horn Island, 1943. Photo: Don Myers via the Torres Strait Heritage Museum.

Training for this initial company of Torres Strait Islanders began in late 1941, with a complement of 120. It is interesting to note that initially the enlistment of the Torres Strait Islanders was not welcomed by the Australian Government, as the Military Board’s Policy of 1940 dictates. This policy prohibited Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders from enlisting, as they were not of ‘European Origin’, with their service being neither necessary nor desirable. The raising of a company of Torres Strait Islanders seemed to be in violation of this policy.

However this provides that no person will be enlisted voluntarily unless he is of substantially European origin and descent. This is only an order and does not affect the legal position and moreover could be varied or waived by a direction by Head Quarters. So far as is known, no such direction has been given but unless it has, the enlistment of Torres Strait Islanders was a breach of this order though perfectly lawful.(3)

These early recruits were quickly trained and then utilised in the defence of Thursday Island. There were several points on the island to be defended. These included the fixed armament, which constituted the 4.7 inch gun and one anti-aircraft searchlight at Milman Hill; the wireless station; the supply stores; jetty; reservoir; power house; post office and oil depots. Due to the small number of troops on the island, the fixed armament was to be defended first, followed by the reservoir and then power house.(4) Other troops consisted of Royal Australian Artillery members, Royal Australian Engineers and the 49th Garrison Battalion.

"These men look fine and savage in uniform . . ." Photo: Mrs Godtschalk, via the Torres Strait Heritage Museum.

By July 1942, the Torres Strait Company was utilised in a counterattack role, still defending the previous mentioned positions on Thursday Island, however, numbers would soon grow to allow members to be stationed on neighbouring Horn Island.

Another recruitment drive began in June 1942, with a great increase in volunteers.(5) The reasons for this increase in volunteers can be attributed to several reasons. At this time of the year all the men were home from their respective marine industry jobs, and as such were available for enlistment. The other reason can be attributed to the known presence of the Japanese forces in the Torres Strait. This presence included Japanese submarines, air raids on Horn Island, and several incidences where the Japanese had machine-gunned villages. The Australian Government provided the vessel Melbidir to travel throughout the Torres Strait Islands, collecting those who wished to join and transporting them to Thursday Island.

Whap Charlie was one of the many who joined.

I was part of the crew of the Melbidir, the Government boat. I was the cabin boy. We went to Murray Island for recruiting there, all schoolboys, just 16 and 17 years old. They just left school and joined the Army. When we went to Thursday Island I saw No. 1 Platoon, No. 2 Platoon, and No. 3 Platoon like a snake, in perfect lines, marching along the road. It got my heart beating, so I signed up there on Thursday Island. They sent me to Pioneer Company.(6)

Such were the numbers of recruits, that the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion was formed, with a full compliment of 830 Torres Strait Island men, 40 Torres Strait Malays and mainland Aboriginals. Training was per the Australian Army syllabus, with rifle drills, marching practice, Bren gun and .303 rifle practices. They participated in joint exercises with other units, the construction of slit trenches and other defensive positions, reconnaissance patrols, dispersal of stores and ammunition. The training was intense with participation in tactical exercises focussing on attack, defence and patrolling, sniper and stalking exercises. One member of the forces reported:

These Islanders are a fine strong looking lot of men. They look well and savage in uniform. They are keen as mustard and can give us lessons in drilling and marching. I would rather fight with them than against them. If ever any trouble starts I should like to have a few of the boys handy.(7)

The Battalion’s first Commanding Officer was Major Jock Swain, who had been on Thursday Island since March 1941 with the 49th Garrison Battalion. He remembers them fondly as being hard-working excellent soldiers.

"Many big jobs were done by the TSLI Battalion troops. During the Coral Sea Battle they unloaded and dispersed 7,000 tonnes of aviation fuel at Horn Island in five days - a great achievement considering the lack of facilities."(8)

On Horn Island members of the Battalion were part of the coordinated effort of Army and Air Force units to defend the island base. The primary defensive positions were the airstrips, thus reflecting the positioning of troops around these two airstrips and general aerodrome area. During the early months of 1942, Horn Island had little in the way of infantry troops, anti-aircraft weaponry or fighter aircraft. This Battalion was one of just two infantry units given the responsibility of the airstrip’s protection. As at July 1942, two rifle platoons of the Company were to defend the Central Sector, with one rifle platoon of B Company and three mortar detachments of the 14th Garrison Battalion providing support. This Central Sector included the area from the wharf extending east around the coast to King Point, then from King Point to a line running north-south through the airstrip area to Double Hill.(9)

D Company, Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion on morning parade, Horn Island, 1943. Photo: Longmore via the Torres Strait Heritage Museum.

During 1943, the Torres Strait Light Infantry Pioneer Company was formed, with a compliment of 160 men. The reason for this formation was twofold. The first reason was due to the high numbers of Torres Strait Islanders volunteering for the Battalion, thus providing an excess of numbers. The second reason was to assist engineering units in the area with the construction of installations. The main engineering unit to be assisted by the new company was the 17th Australian Field Company, with jobs such as the Thursday Island wharf, water scheme for Horn Island, and a variety of buildings being undertaken. This Company came under the command of Major Mitchell, a veteran of the Middle East.

To assist the myriad of vessels traversing the waters of the Torres Strait, the 2nd Australian Water Transport Company was formed in early 1943. This Company had a compliment of 108 personnel, which was a mix of Torres Strait Islanders, Aboriginals and Malays. This unit was instrumental in guiding water craft through the treacherous waters of the Torres Strait. The vessels they assisted included the RAAF rescue launch, which plucked downed airmen from the waters of the Torres Strait. They also directed cargo boats throughout the islands with vital supplies and equipment for troops stationed on remote outer islands. Others were charged with piloting American PT boats through the Torres Strait. Walter Nona was one such pilot, and he recalls.

We guided the American PT boats from Thursday Island to Merauke or Daru. They were very fast. We would leave Thursday Island at 8am and get to Daru by teatime, 10pm. They had depth charges onboard in case we find the Japanese submarine, then the action would start.(10)

As the troop and airmen numbers in the area continued to grow during 1943, the administrative and logistical needs also increased hence the need for other units to support the fighting troops and airmen. These units included postal units, bakery, dentist, and members of the Salvation Army. Additionally there became an attraction for locating local foodstuffs, which would prevent the cost of transporting perishable foods over long distances, and the problem of short-term storage in conditions that were not conducive to their preservation. The solution was to form farming and marine supply units in operational areas, hence the formation of the 4th Aust. Marine Supply Platoon in August 1943. Ten members of the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion volunteered for service in this unit, with the objective being the supply of marine food to the 1st Aust. Camp Hospital on Horn Island and the 6th Aust. Camp Hospital on Thursday Island. Combined with eleven recruits from other units, they set about achieving their objective.

Ray Cook recalls his time in the unit:

There was never any discrimination in those days. We all lived, ate, slept, and worked together and never a cross word was spoken. Everybody was jovial and full of joking. We all shared the clean and dirty work, whether on the boats or at the land camps.(11)

September 1943 saw both ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies being amalgamated into the Mobile Force on Horn Island. This force came under the Horn Island Defensive Plan, which saw the mobile group as being able to challenge any Japanese troops that landed on the island, wherever the location. Their objective was to strike whilst the enemy were disorganised. The newly arrived 5th Aust. Machine Gun Battalion and companies of the 26th Aust. Infantry Battalion provided support for the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion. Members of the Battalion on Thursday Island continued to defend key points on the island in conjunction with engineering jobs and dock operational duties.

B Company, Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion during the March Past for General Blaney in 1944, Thursday Island. Photo: Mrs Godtschalk, via the Torres Strait Heritage Museum.

Major C. Godtschalk, Commanding Officer Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion 1944-1946. Photo: Mrs Godtschalk, via the Torres Strait Heritage Museum

However, other issues soon became apparent in 1943, issues that had been festering since the formation of the Company and subsequent Battalion. These problems were the inequality of payment for the soldiers, their concern over village leadership while they were away, family food problems and other issues of equality. The rates of pay were as follows:

Private

1st year: 3 pounds, 10 shillings per month

2nd year: 3 pounds, 15 shillings per month

3rd year: 4 pounds per month

L/Corporal

4 pounds, 7 shillings and 6 pence per month

Corporal

4 pounds, 15 shillings per month.

(12)

These pay scales were calculated on a comparison between the Papuan New Guinean Constabulary and not the Australian Army. A report on the enlistment of Torres Strait Islanders stated that this method of payment was incorrect.

Neither War Financial Regulations nor Military Financial Regulations provide for different rates of pay for Torres Strait Islanders and they appear to be entitled to full rates and not those which are in operation.(13)

In other units, a non Indigenous private received approximately 8 pounds per month. However the Malays in the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion were paid the same as the non Indigenous soldiers, with Aboriginals paid at the same rate as the Islander soldiers. In addition, there were no allowances provided for the Islander soldiers, even though the Australian Government through a letter from Premier Smith to the Prime Minister approved such a scheme in December 1941.

"It is considered that if these allowances were granted, voluntary enlistment of Thursday Island men would be encouraged if it be decided to proceed with further enlistments. A large percentage of them has a dependent mother, father or some other relative and it is characteristic of this race that they consistently support their dependants."

The Director of Native Affairs disagreed with the process of providing allowances, stating that the usual arrangements in place for natives employed away from their island were to be adopted. As a result the Fortress Commander paid the Torres Strait soldiers one pound, one shilling per month, with the balance allotted to the Protector of Islanders.

Understandably, many of the men resented having to rely on the Protector to support their families.

The leadership of individual villages caused concern for the men whilst they were serving in the Australian Army. With the almost total removal of the men from each island, there was nobody left to provide leadership and to take on the role of Chief Councillor. Each island had been governed by a local election of Chief Councillor and his Councillors since the 1939 Torres Strait Islander’s Act. During leave in 1943, the soldiers were appalled at the deterioration in the villages during their absence, with most of the population living in the caves and scrub on the island, due to the Japanese attacking the villages from the air. Another issue that affected the men’s families was the problem of acquiring food. Since the war began there had been a steady rise in inflation, which saw the costs of food increase, making it increasingly hard to acquire foodstuffs, especially with the men not able to hunt.

Major Jock Swain, Commanding Officer, Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion 1942-1944. Photo Jock Swain, via the Torres Strait Heritage Museum.

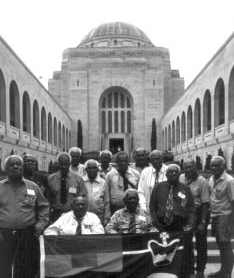

Members of the Battalion visited the Australian War Memorial in November 2000 to attend the Remembrance Day Service. Photo: A.L Seekee

Other contentious issues included the fact that alcohol was not permitted for the Torres Strait Islanders, but was permitted to the white troops and the Malays serving in the Battalion. Malays and white soldiers in the unit were also paid allowances, while the Torres Strait Islanders were not.

The event that brought all of the above issues to a point was the patrol of several Torres Strait Islanders into Japanese held territory in New Guinea. Wing Commander Thompson initially led this patrol,

however, once he sustained injuries, Captain Wolfe took over. The patrol was made up of seven members of the Battalion, with their objective being to explore and report on any enemy activity in the Oba and Wilderman Rivers area of Dutch New Guinea. Mr J. Anu explains their task:

"Some Japanese had been cut off in New Guinea. A patrol was sent to try to catch some for getting information. I volunteered and went to Merauke. We went out to the Murphy River in the launch Rosemary and then we used a little pilot boat that came from Thursday Island. We had to travel inland in the rivers as it was too dangerous out in the sea."(14)

On the 23rd December 1943, the patrol engaged the Japanese on the Oetoemboewee River, with heated fire exchanged between their boat and the Japanese barge they encountered around a bend in the river. Four of the group were slightly injured, with one severely injured and one killed. The men were transported to Merauke via a Naval vessel, and from there to Horn Island, with the exception of the one seriously injured who remained in Merauke.

Upon their arrival back at Horn Island Cpl J. Anu spoke to his platoon commander Lt. Linklater concerning promises of extra pay for their New Guinea service. The Lieutenant in turn reported to Captain Godstchalk, commanding officer of ‘D’ Company. The NCOs were paraded before Captain Godstchalk where they explained that since they had taken the same risks as a white soldier during the patrol work, they should receive equal pay. It was pointed out to the soldiers that the rate of pay would not increase because they had served in another area for a period of time. However, in his report Captain Godstchalk realised that the issue was not just an increase for the men of the patrol, but for the Battalion as a whole. The Military Board had recognised the problem of unequal pay scales in January 1942:

"...it has clearly been established that differentiation in matters of pay and the like have created such subdivisions and have had harmful effect on the Forces." (15)

Underpaid, worried about their families, frustrated at the political situation on the outer islands and additional issues of inequality, the Torres Strait Islanders instigated a mutiny. On the 30th December 1943, ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies of the Battalion went on strike. They had seen strikes used as an effective means of expressing grievances in the Pearling industry of the Torres Strait pre World War 2. However, the Army saw it as a mutiny. Major Swain, Commanding Officer of the Battalion paraded the three companies and explained that it was not up to the officers of the Battalion to grant extra pay. However, he would pass their grievances further along the Military chain of command.

A result was achieved on 1 February 1944, when a Departmental Conference was held in Melbourne to address the topic of ‘Natives in the Military.’ The main point of discussion was the payment of the members of the Battalion; the second point was the practice of employing different types of Natives and Malays in the same area at differing rates of pay. The Conference decided that legally the Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal servicemen were entitled to full rates of pay. However, payments were not to be made. Their reasons included the enormous cost of back payment at the full rate, the second was if the men were paid at these rates, which were far higher than what they achieved in civilian life, it would cause trouble when they left the Army. It was decided however to grant the Torres Strait Islander soldiers an increase, raising their pay to 66 percent of that which the white soldiers were paid. The War Cabinet approved this raise on the 20th March 1944, with the proviso that payment would still be made to the Director of Native Affairs.

A further result saw all Malayans transferred to other units and all Aboriginals discharged from the Army. The problem of village leadership was rectified with voting conducted for village councillors and Chief Councillor. Those chosen were released from the Army in September 1944 to fulfil their duties as leaders on the outer islands. Upon their arrival onto their islands, they utilised skills acquired whilst in the Army, improving hygienic and living conditions in their home villages.

By December 1944, a lack of trained specialists in the Torres Strait area led the Fortress Commander on Thursday Island to request that the Battalion be trained in more specific roles. These included heavy vehicle drivers, motorcycle riders, shipwrights, crane drivers, carpenters and plumbers amongst other trades. As a result of successful training, the unit was employed in the role of a Docks Operating Company, with a small ships platoon, general transport platoon and a port maintenance platoon. During 1945, the Battalion was the last to be stationed in the Torres Strait, with all others either moving further north, or being disbanded. Hence by 1946, the unit was slowly disbanded, with all members returning to their home islands.

However, the men had changed. Post World War 2 in the Torres Strait would be a vastly different place than that of the pre War. The men had acquired new training and skills that were previously unobtainable to them in pre war life, thus enabling them to gain better-paid and more responsible occupations. They thus became empowered to make changes and improvements to the Torres Strait. These changes in attitude and training are still being felt today, some 56 years after the cessation of hostilities.

Major Jock Swain, the Battalion’s first commanding officer, 1942-1944 recalls the men:

"All who served with the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion should be proud of their efforts during World War Two. I am sure that put to the test, their performance would have been excellent."(16)

Major Godstchalk, commander of the Battalion in 1944-1946 recalled the men he served with.

"As soldiers they were physically, morally and intellectually well above the average of men drawn from any other community, whether it be Australian, New Zealand, Indian or Great Britain. For this I can personally vouch. Intelligent and naturally bright, they quickly and easily absorbed the various military skills of an infantry battalion." (17)

Tom Cole of the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion meets members of the 51st Battalion Far North Queensland Regiment, Charlie Company, the grandchildren of those he once served with, September 2001. Photo: A.L Seekee

Idai Kawiri, a veteran of the Battalion and a young member of the 51st Battalion Far North Queensland Regiment, Charlie Company, September 2001. Photo: A.L Seekee

Today, members of the Battalion march in the ANZAC Day parade, and take part in various commemorative days and functions. The largest function of recent days was the trip to Canberra to take part in the 2000 Remembrance Day ceremony at the Australian War Memorial. Wreaths were laid for the first time at the War Memorial to remember the 36 members of the Battalion who lost their lives whilst in the service of their country. The Battalion’s grandchildren today serve in the 51st Battalion Far North Queensland Regiment, Charlie Company, Torres Strait, proudly marching on in the footsteps of their forebears.

For more information on the Torres Strait during World War Two, the author may be contacted on intheirsteps@hotmail.com

or via PO Box 6, Horn Island, Qld 4875.

Vanessa Seekee. Horn Island, In Their Steps, 1939-1945 was released in December 2001.

An education kit produced by the author Spirit of ANZAC: A Torres Strait Perspective, with activities for Years 1-12, is available from the Thursday Island RSL Sub-branch.

Endnotes:

Aborigines did serve, but in unit strengths, or as individuals within units.

National Archives of Australia, Melbourne, Series MP 508, item 275/701/328. ‘Letter from the Acting Prime Minister Collins re the Torres Strait Islanders for Thursday Island Garrison’.

AWM 54:628/1/1: ‘Enlistment of Torres Strait Islanders.’

AWM 54 243/6/108: Appreciation of the Situation by Lt. Col .R.J.R. Hurst, 12th July 1941.

This increase led the Torres Strait Company to be officially renamed the Torres Strait Light Infantry.

Torres Strait Heritage Museum, Jock Swain Sound Archives: ‘Interview with Whap Charlie, 1998.’

AWM 60, 9/785/12: ‘HQ Qld L of C, Intelligence Report for the week ending November 20th, 1942.

Torres Strait Heritage Museum, Jock Swain Sound Archives: ‘Interview with Major Jock Swain, January 1997.’

AWM item 01/42: Thursday Island Fortress, Operation Instruction No.2.

Torres Strait Heritage Museum, Jock Swain Sound Archives: ‘Interview with Walter Nona, November 2000.’

Torres Strait Heritage Museum, ‘Correspondence with Ray Cook.’

National Archives of Australia, Melbourne Office., MP 508, item 275/701/361. ‘Employment of Torres Strait islanders on Military Duty, Thursday Island.’

AWM 54, 628/1/1, ‘Enlistment of Torres Strait Islanders.’

Torres Strait at War, Thursday Island State High School, 1989.

Letter from the Secretary of the Military Board to the Secretary Department of the Army, 25 Feb 1942.

Swain, Jock ‘A Short History of the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion.’

Sydney Morning Herald, 17th December 1965.