There were five points during the war at which we can see Australia either asserting its identity, or remaining tied subserviently to another nation.

In 1939, Britain declared war against Germany - the Prime Minister Menzies announced that we were therefore also automatically at war.

As part of a pre-war agreement commitment Prime Minister Menzies turned the Navy over to effective control by Britain as part of the Royal Navy. Menzies also committed Australia's Air Force to British command for use in the war over Europe, and in effect the RAAF's main role became training Australian crews to be used in the RAF. This later severely restricted the RAAF's capacity to play an effective role in the Pacific War.

In December 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbour and then Singapore, Australia declared war on Japan. We did not wait for a British declaration, nor did we consider ourselves a part of the British declaration.

In late 1941 and early 1942, as Japan stormed into the war and invaded New Guinea, most Australian troops were in action in the Middle East. Australian Prime Minister Curtin wanted the troops to return to Australia, to be sent to New Guinea. British Prime Minister Churchill wanted to send the troops to Burma to take on the Japanese there, assuring Curtin that this was the better strategy, and that New Guinea could be dealt with later. Curtin's decision won the day.

One effect of that was that the Commonwealth Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act. The Statute of Westminster was a British Act which said in effect that when a Dominion adopted it, the British government could no longer make any decisions for that Dominion. It had been available to Australia since 1931, but was only adopted in 1943.

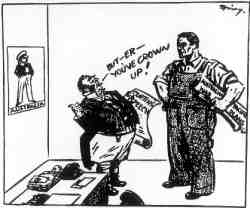

The cartoon above appeared in the 'Sydney Daily Telegraph' in 1941. The person on the left, representing Britain, is holding a document entitled "Curtin's Speech." The person on the right, representing Australia, is holding a document entitled "Australian Pacific War Plans".

In December 1941, Curtin wrote an article for the Melbourne Herald, in which he said: 'Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.' The United States needed Australia as a supply and staging post for its Pacific War efforts; Australia needed the USA to be active and aggressive in the Pacific.

United States troops started pouring into Australia from Christmas Eve 1941. The American General Douglas MacArthur was the supreme commander of all Allied forces in the Pacific. He insisted that he deal only with Curtin. Curtin looked to him for military advice and expertise, and in effect withdrew Australian influence from the running of the war. Some historians see this as a 'surrendering of sovereignty'. Towards the end of the war Australia's interests were perhaps not well served as MacArthur deliberately cut the Australians out of the war effort, and committed them to a series of 'mopping up' campaigns against the Japanese that were of doubtful strategic value, but were costly in Australian lives.

To investigate this aspect of the Home Front experience by using evidence from the time, see Home Fronts at War, Ryebuck Media for ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee of Queensland.

More about the book HOME FRONTS AT WAR