Gas was first used at the battle of Neuve Chapelle in October 1914 when the Germans fired shrapnel shells in which the lead balls had been treated with an irritant chemical. Their first major use of gas occurred on 22 April 1915 when they released chlorine from pressure cylinders in the Ypres Salient. The clouds of greenish vapour took the British and French by surprise.

Choking and vomiting, many British and French troops fled in panic, leaving a five-kilometre gap in the defences. The Germans, unaware of their success, failed to exploit it. Soldiers were advised to hold a cloth soaked in urine over their mouth and nose; the ammonia in the urine neutralised the chlorine.

Australians at ANZAC were given pads impregnated with bicarbonate of soda to be tied over the mouth and nose. While still at ANZAC they were issued with hoods impregnated with hyposulphate of soda, but they were never necessary. The hypohelmets, as the Australians called them, were useless against phosgene mixed with chlorine, which the Germans used at the end of 1915.

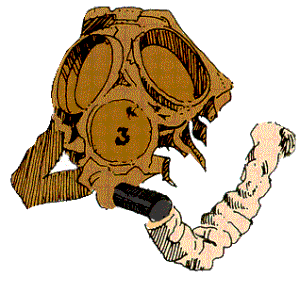

Soon after the AIF reached France in spring 1916 they were issued with a box respirator which filtered the gases. Worn on the chest, it was connected to the face piece by a rubber tube. Separate goggles protected the eyes against tear gas. A respirator developed at Melbourne University early in 1915 influenced the development of the effective box respirator which all British and Empire troops had by 1917.

The British caught up with German development and from 1916 both sides increasingly used gas-filled shells, fired from guns, mortars and spring-loaded projectors. In mid-1917 the Germans fired mustard gas, dichlorethyl sulphate, known as yellow cross because the shells were so marked. More like an oil and odourless, it took Allied troops by surprise, especially as its worst effects, severe skin blistering and serious lung congestion, did not appear for several hours. Mustard gas remained potent for weeks in mud and heavy soil.

By March 1918, before any attack, the Germans fired mustard gas on the flanks of the area selected for attack, to block support, and a less lethal, low-persistency gas on the front, so that the German attackers themselves would not be badly affected.

They often masked a mustard gas attack with high-explosive shells as well as sneezing gas - chemically diphenyl chlorarsine, or blue cross in soldiers’ talk - which made it difficult to keep the respirators on. The Australians had to wear masks throughout a bombardment and few could sleep with them on.

The Germans drenched back areas with mustard gas and Australian casualties were sometimes heavy. For instance, after heavy gassing the 4th Division’s artillery was withdrawn on 25 October 1917. In October and November that year 1,313 gunners became casualties and 20 of them quickly died.

Thousands of Australians were affected by gas and about 200 died from it - a small number considering the overall casualties. Mustard gas caused the majority of gas cases. It stripped the mucous membrane from the bronchial tubes and caused pain beyond endurance. Most sufferers had to be strapped to their beds and death took up to five weeks. Chlorine, phosgene and chloropicrin damaged the respiratory organs. Each gas had its ghastly effects. Severe chlorine gassing led to slow death by asphyxiation. The Diggers said that chlorine smelt like a mixture of pineapple and pepper, phosgene like rotten fish.

Despite extensive efforts, neither the AIF’s best known expert in anti-gas procedures, Captain A.L. Rossiter, Gas Officer of the 4th Division, nor anybody else found a protection against mustard gas which fell on the soldier’s skin.