In 1916 Prime Minister Hughes proposed raising the numbers needed to maintain Australian troops at full strength at the Front by conscripting those who to date were unwilling or opposed to enlisting to fight.

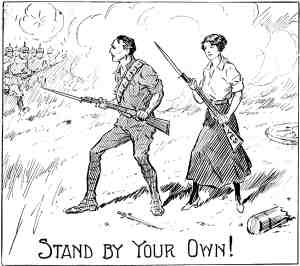

A poster from the time. The butt of the rifle carried by the woman has "YES" emblazoned on it.

The government already had the power under the existing provisions of the Defence Act to conscript men - but only for service in Australia. They could not be sent overseas to fight.

All the government needed to do was to change the Defence Act to extend the existing power of conscription for home service, to overseas service. All it had to do to achieve that change in legislation was to pass an amendment through both houses of parliament - the Senate, and the House of Representatives.

But there was a problem. Some members of the Labor Government were against conscription. Hughes knew that he had enough supporters of conscription among the Labor and Liberal parties to have a majority in the House of Representatives; but he was a few short of a majority in the Senate.

To overcome this problem Hughes decided to hold a national vote on the issue.

This vote is sometimes called a referendum, and sometimes called a plebiscite. Strictly speaking a referendum is a vote to change the Constitution. There was no need to change the Constitution in this case, as the Constitution already gave the government power to introduce conscription. So the vote was in effect a national ‘public opinion poll’ on the issue. The vote would not mean anything officially - but what Hughes planned was that he would be able to use the public vote in favour of conscription to persuade a few Senators to change their vote in parliament. Even though the Senators were personally against it, the vote would show that the people they represented in fact wanted conscription, so the Senators would accept the people’s wishes. That was the theory.

The supporters and opponents of conscription started campaigning vigorously on the issue. The campaign literature of each side was often bitter and divisive. Each side presented its side as the moral and loyal thing to do, while the other’s approach would be disastrous.

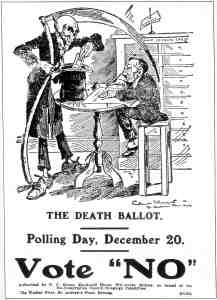

A poster from the time.

The vote was very close - with conscription being rejected 51 to 49 per cent.

Many commentators asked why conscription was rejected. A better question may be, why was the vote so close?

One reason why so many opposed conscription was that it provided a focus for a lot of different points of view about the war. Some people opposed the war; others were opposed to conscription as a principle; others were saying that they were hurt by the economic situation of the war, and were protesting against that; still others were voting to protect unionism; others were protesting at the British treatment of the rebels in Ireland. Normally these people might not have agreed with each other on many things, but they all agreed on the conscription question, and the issue gave them all a chance to express their opposition.

In 1917 Hughes held another vote on the issue. This time he actually had a majority in both Houses of Parliament, and did not need the vote. He wanted, however, to give the people another chance to overcome what he saw as their great mistake in rejecting conscription the previous year - a chance to redeem themselves. The campaign was again bitter and divisive, and conscription was again defeated, this time by a slightly larger margin.

To investigate this aspect of the Home Front experience by using evidence from the time, see Home Fronts at War, Ryebuck Media for ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee of Queensland.

(More about the book HOME FRONTS AT WAR)